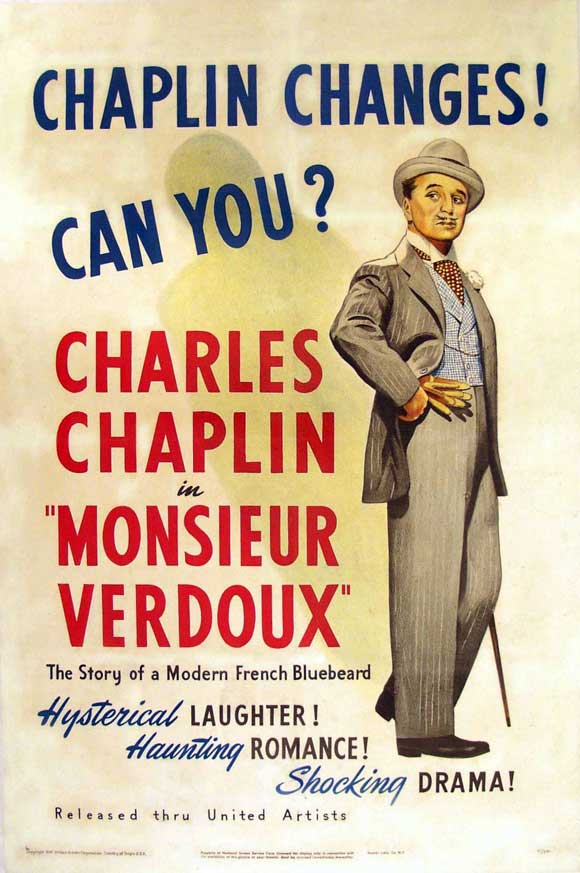

Monsieur Verdoux (1947)

Directed by Charles Chaplin

United Artists

Monsieur Verdoux, “a comedy of murders,” is a product of Charles Chaplin’s Frantic One-Man Band. Besides starring in the film, Chaplin is credited with directing the picture, writing the screenplay, producing the film, and writing the music. Orson Welles wrote the original script and was slated to direct Chaplin in the picture, but at the last minute, Chaplin decided that he didn’t want to be directed by someone else — he’d always been his own director in the past — and bought the script from Welles, crediting him with the “idea” for the film.

The film is based on the career of real-life murderer Henri Désiré Landru, who between 1914 and 1918 seduced a number of women and murdered them after gaining access to their assets. He burned their dismembered bodies in his oven, disposing of them completely, which made prosecuting him a challenge after he was caught. A trail of paperwork and other evidence was enough to eventually convict him of 11 counts of murder (10 women and one of their teenaged sons), and he was executed on the guillotine in 1922.

In Monsieur Verdoux, Chaplin plays a man named Henri Verdoux, who describes himself as an “honest bank clerk.” Honest, that is, until the Depression of 1930, at which point he began his new career, “liquidating members of the opposite sex.” He claims that he began his career as a Bluebeard strictly as a business proposition. This is utter claptrap, as is nearly every other word out of M. Verdoux’s mouth that isn’t plot-advancing dialogue, but we’ll get to that later.

The film takes place in 1932. M. Verdoux had a 30-year career in banking before he began his new career as a murderer, and with his dainty, foppish clothes he looks like a relic of another time. When the film begins, he is living in a villa in the south of France. He’s a tidy little man who loves to garden, but whose incinerator has been going full-blast for the past three days. He’s kind to animals, moving a caterpillar out of his way in the garden path and feeding a cat on the street. M. Verdoux is even a vegetarian.

He is also a lothario with an insatiable appetite for well-heeled widows. But this, M. Verdoux assures us, is just his day job. His heart belongs to his wheelchair-bound wife Mona (Mady Correll) and adorable little boy Peter (Allison Roddan). At home, M. Verdoux lectures Peter when he catches him pulling the cat’s tail that “violence begets violence.” He also tells his son that he has a mean streak. “I don’t know where you get it!” he exclaims.

Aside from the saintly Mme. Verdoux, nearly everyone in the film is a grotesque and obnoxious caricature. In this way, Monsieur Verdoux is a distillation of Chaplin’s career-long vacillation between sentimentality and cruelty. A perfect example of this is the scene in which M. Verdoux brings a girl in off the street to poison her, but thinks better of it after she speaks of how wonderful life can be, and how she loved her husband, crippled in the war. (The girl is played by 20-year-old ingenue Marilyn Nash.)

The few bits of physical comedy in the film are funny, but they’re mostly either too brief or out of character with the rest of the scene in which they take place. Several comedic scenes — such as when M. Verdoux and another man start slapping each other with rapid-fire speed, or when M. Verdoux is romancing the older woman who was going to buy his villa in the beginning of the film, and he’s moving ever closer to her on the couch — fade to black in a quick, unsatisfying way.

When Monsieur Verdoux was released, Chaplin’s reputation was severely tarnished. He hadn’t made a film since The Great Dictator (1940), and he was under attack for both his Leftist political sympathies and his morals (he was the subject of a sensational paternity suit, and was a serial seducer of young women, many of them underage).

Monsieur Verdoux can be seen as a defiant stand against his critics. It’s the blackest of black comedies, and was a box office disaster in the United States when it was first released (it fared a bit better in Europe), but has built up quite a cult since it was re-released to receptive audiences in the ’60s and ’70s. At the time of its release, however, it polarized critics. James Agee crowned it a masterpiece, and the National Board of Review named it the best English-language film of 1947. Others were less enthusiastic.

I think that Monsieur Verdoux is a deeply flawed film. Chaplin was the preeminent clown of the silent era. He wasn’t quite the master technician of hijinks that Buster Keaton was, but he was able to convey a panoply of emotions through his face and body. His films are not only some of the funniest of the silent era, but are emotionally affecting, too. The ending of City Lights (1931) is still one of the most powerful I have seen in any film.

When he was able to speak onscreen, however, Chaplin was a tedious hack who only thought he was profound. Monsieur Verdoux isn’t as crushingly pretentious and boring as his later film Limelight (1952), but it has its moments.

The end of Monsieur Verdoux is especially problematic. Speaking on his own behalf in court, M. Verdoux says, “I was forced to go into business for myself. As for being a mass killer, does not the world encourage it? Is it not building weapons of destruction for the sole purpose of mass killing? Has it not blown unsuspecting women and little children to pieces? And done it very scientifically? As a mass killer, I am an amateur by comparison. However, I do not wish to lose my temper, because very shortly, I shall lose my head. Nevertheless, upon leaving this spark of earthly existence, I have this to say: I shall see you all… very soon… very soon.”

The problem with this is that the murders of dowdy and grotesque women that we’ve seen M. Verdoux carry out in the film are very different from the mass mechanized killing of the Great War or the genocidal horrors of World War II. They’re intimate crimes, carried out for personal gain, and occasionally hilarious, such as the sequence in which M. Verdoux is repeatedly foiled while attempting to drop a noose around one of his wives’ necks while they are out fishing. It would be one thing if Chaplin were presenting M. Verdoux’s crimes as symptoms of a sick society, but what he seems to be doing is using a sick society as a justification for M. Verdoux’s crimes.

Is M. Verdoux meant to be an unreliable narrator? Perhaps, but he never comes across that way. I think that Chaplin was simply too infatuated with himself to present M. Verdoux as anything but a lovable cad, which makes the entire film uncomfortable and off-putting in ways I’m not sure Chaplin ever intended.