Wagon Master (1950)

Directed by John Ford

Argosy Pictures / RKO Radio Pictures

I have mixed feelings about John Ford.

I absolutely love some of his films, and consider them masterpieces, but he also made a lot of films that I’m not crazy about even though every other classic film fan seems to revere them, like She Wore a Yellow Ribbon (1949).

After watching Wagon Master, which was the western that Ford directed after She Wore a Yellow Ribbon, I’m beginning to think that my expectations might play some role. (In between these two westerns, Ford directed the comedy When Willie Comes Marching Home, which I haven’t seen.)

High expectations and the reverence of others can sometimes make a film tough to enjoy. I thought that She Wore a Yellow Ribbon was stunningly photographed, and I liked some of the performances, but overall I found it poorly paced, historically inaccurate, and unbearably sentimental. I also really didn’t like John Wayne’s performance. I love it when the Duke plays variations on himself, but whenever he plays a “character” I find it hard to watch. His role as Nathan Brittles in She Wore a Yellow Ribbon isn’t as bad as when he played Genghis Khan in The Conqueror (1956), but I still found his “old man” schtick disingenuous and poorly acted.

Wagon Master, on the other hand, is a film almost no one ever talks about. When I sat down to watch it, I had no expectations, nor anyone else’s reverence to contend with.

I really enjoyed it. I thought it was a poetic and leisurely paced western that I’d love to see again some day. Unlike Ford’s last two westerns, which were both shot in Technicolor, Wagon Master is shot in black and white. (At least until the 1960s, I think I prefer my westerns in black and white.)

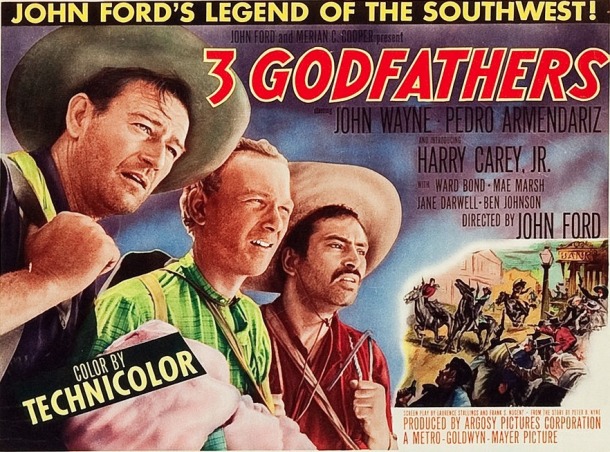

In Wagon Master, Ben Johnson and Harry Carey Jr., who both had supporting roles in She Wore a Yellow Ribbon, play a pair of horse traders named Travis and Sandy.

They’re approached by a group of Mormons who are led by a recent convert to the faith, Elder Wiggs (Ward Bond), whose constant struggle to not use profanity is a running joke in the film. The group of Mormons are heading west through desolate stretches and need experienced range riders like Travis and Sandy to guide them. The Mormons plan to found a settlement and begin growing crops so a much larger group of their brethren will be able to join them in their promised land a year later.

The range is full of dangers, including human ones, who come in the form of the murderous Clegg gang. They’re led by Uncle Shiloh Clegg (Charles Kemper). If you pay close attention you’ll spot future Gunsmoke star James Arness as another member of the gang, Floyd Clegg.

The Clegg gang is menacing, but there are also friendly strangers who join the wagon train along their journey — a drunken snake-oil salesman named Dr. A. Locksley Hall (Alan Mowbray) and his two female companions, Fleuretty Phyffe (Ruth Clifford) and Denver (Joanne Dru).

Perhaps if I were to proclaim Wagon Master a masterpiece, it would collapse under the weight of my approbation. But I thoroughly enjoyed it, and thought it was a beautifully made film that unfolds at a perfect pace.

I especially enjoyed seeing Ben Johnson come into his own as an actor. The Oklahoma-born Johnson was a ranch hand and rodeo rider in real life, and he’s convincing and charismatic in this role. I liked his supporting role in She Wore a Yellow Ribbon, but he carries the film here, and emerges as a great western star. He has no false bravado or unrealistic heroics, and even decides against pulling his gun at several times when the audience might expect him to.