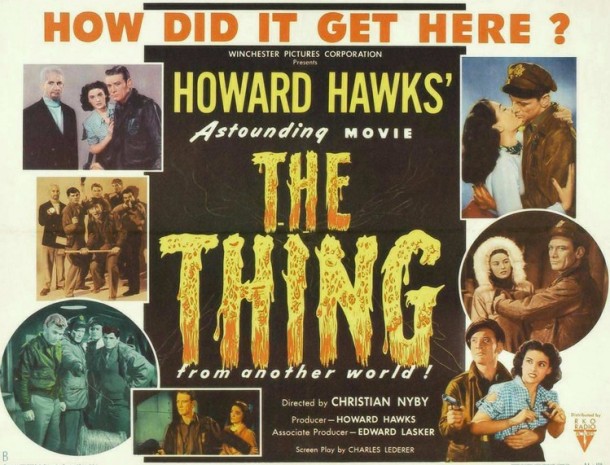

The Thing (From Another World) (1951)

Directed by Christian Nyby

RKO Radio Pictures / Winchester Pictures

I’m probably one of the few people my age who fell in love with the original version of The Thing before seeing John Carpenter’s 1982 version. Back in high school, I’d watch any piece of 1950s sci-fi schlock at least once, but The Thing (From Another World) was far from schlock, and I watched my VHS copy at least six or seven times when I was a teenager, maybe more.

In fact, I loved The Thing so much that I didn’t really like John Carpenter’s remake the first time I watched it. I loved the optimistic, capable characters in the original and all their rapid-fire, overlapping dialogue, and I found Carpenter’s version pessimistic and depressing. However, like most of Carpenter’s films from the ’70s and ’80s, The Thing gets better every time I watch it, and it’s now easily one of my favorite sci-fi/horror films.

Revisiting the original version of The Thing was a strange experience, at least for the first 20 minutes. I hadn’t seen it in a long time, and Carpenter’s version has in many ways replaced it in my heart.

Once you’ve seen the innovative, gory special effects of Carpenter’s version, it’s hard to go back to James Arness in a bald cap, spacesuit, and claw hands. The 1951 version also lacks the central idea of a shape-shifting alien who can mimic human form, so there isn’t the same level of paranoia, which is a huge part of Carpenter’s version.

After the first couple of reels, however, I settled back into the rhythm of the original and enjoyed it as much as I always did. It’s a completely different movie from Carpenter’s version, and what it does, it does brilliantly. It may not have much in the way of paranoia, but it’s a suspenseful film that establishes a real sense of isolation and claustrophobia.

One thing that struck me on this viewing of The Thing is how much of its gruesomeness and horror is dependent on the viewer’s imagination. Descriptions of things like a plant-based alien-humanoid who lives on blood or scientists hanging upside down with their throats slashed are only referred to in dialogue. This probably played better for audiences weaned on radio dramas, and I’m not sure how well it will hold up for younger viewers accustomed to explicit shocks. On the other hand, the decision of the filmmakers to keep the alien monster mostly off-screen has dated the film well.

The Thing holds up as superior entertainment that is head and shoulders above most ’50s sci-fi movies. The cast is full of actors who never became household names, but they deliver deft character work and seem like real people. What the film lacks in budget it more than makes up for with an intelligent script and tight pacing. It’s a terrific movie that I can watch over and over, and it still feels fresh.