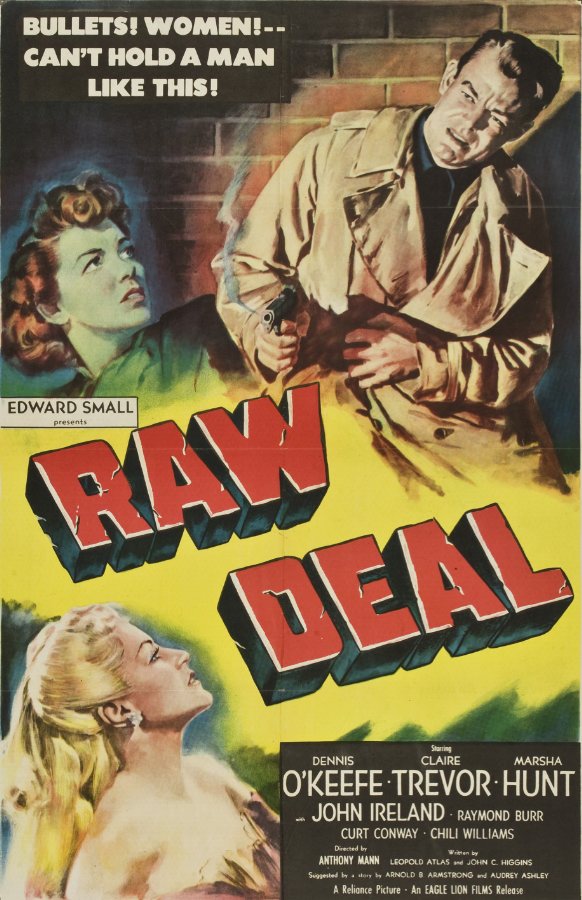

Raw Deal (1948)

Directed by Anthony Mann

Eagle-Lion Films

Anthony Mann’s T-Men (1947) and Raw Deal (1948) together form one of the most powerful one-two punches in the history or film noir.

Both films star Dennis O’Keefe, both feature musical scores by Paul Sawtell, John C. Higgins has a writing credit on both, and both feature the exquisite cinematography of John Alton.

What makes these two films such a great one-two punch is that they are each one side of the film noir coin. T-Men is a docudrama, purportedly made to show square-jawed agents of the Treasury Department cracking a big case, but like all great noir docudramas, the depiction of the criminal demimonde and the gray areas of its protagonists’ moral codes are the most interesting parts of the film.

Raw Deal is the other side of the coin. It’s a film noir purely about crime and criminals, and it has all the great elements of noir — a doomed male protagonist on the run, a “good girl” and a “bad girl” competing for his love, dream-like voice-over narration, a casually sadistic villain, and it’s set in one of the great noir cities — San Francisco.

Like Billy Wilder’s Double Indemnity (1944), Edgar G. Ulmer’s Detour (1945), and Jacques Tourneur’s Out of the Past (1947), Raw Deal is the Platonic ideal of a film noir.

Raw Deal begins with aging gun moll Pat Cameron (Claire Trevor) going to visit Joe Sullivan (Dennis O’Keefe) in prison. Right away Raw Deal establishes that it is not a run-of-the-mill crime film, as Claire Trevor’s voice-over narration is accompanied by a haunting theme played on a theremin. The element of the theremin is only present in Paul Sawtell’s score during these voice-overs, and establishes Pat’s point of view as dreamy and hyperreal. Raw Deal is the first film in which I’ve heard a theremin since Miklós Rózsa’s masterful scores for Billy Wilder’s The Lost Weekend (1945) and Alfred Hitchcock’s Spellbound (1945), both of which used the eerie sound of a theremin to establish altered states of perception.

When she arrives at the prison, however, Pat is told she has to wait a little while because Joe already has a visitor — Ann Martin (Marsha Hunt). Ann works for Joe’s defense lawyer’s office and she cares about his case and wants to see him paroled, but she admits that he will probably have to wait at least three years. She leaves, Pat enters, and Joe is faced with a more tantalizing prospect. Gang boss Rick Coyle (Raymond Burr) has devised an escape plan for Joe. If he can make it over the wall Pat will be there waiting in a getaway car.

Of course, nothing is what it seems to be on the surface, and Coyle — whose double-cross is how Joe ended up in prison in the first place and who still owes Joe his cut from a robbery — is hoping that Joe will be shot by prison guards during his escape, taking care of Coyle’s problem for good.

Burr formerly played a memorable villain in Mann’s noir Desperate (1947), but he’s an even nastier and more violent character in Raw Deal, casually setting his girlfriend on fire in a shocking scene of cruelty that presages a similar scene in Fritz Lang’s The Big Heat (1953). His right-hand man, the bizarrely named “Fantail,” is solidly played by John Ireland, who formerly starred in Mann’s noir Railroaded (1947).

First and foremost, Raw Deal is a masterpiece of suspense. For most of the movie Joe, Pat, and Ann are on the run from the police, and the film hits all of the classic “fugitive movie” moments — navigating a road block, hiding out in a cabin in the woods, one narrow escape after another, etc. Finally, for the last act of the film, the type of suspense changes, and a ticking clock takes the film closer and closer to its inevitable violent confrontation.

Since so much of Raw Deal takes place on the open road, there aren’t as many opportunities for Alton to flex his cinematographic muscles in the same way he did in T-Men, which mostly took place in urban environments. But he makes the most of what he has to work with. There’s a lot of day-for-night shooting in Raw Deal, and it’s a technique that never looks quite right, but at least with Alton operating the camera it always looks good. Finally, scenes toward the end with Claire Trevor’s face reflected in a ticking clock as she weighs a decision in her mind are absolutely masterful.

Anthony Mann was a great director who made wonderful films in all genres, but among his film noirs, I’ll never be able to decide if I like Raw Deal or T-Men better. They’re both great, must-see pictures for every aficionado of film noir.