Strangers on a Train (1949)

Directed by Alfred Hitchcock

Warner Bros.

Sometimes I think that Hitchcock’s black & white films don’t get enough love (aside from Psycho, which is one of his most modern and accessible films).

Strangers on a Train is one of my favorite Hitchcock films, and I think it’s criminally underrated. It’s been awhile since I’ve seen it, but it held up wonderfully. I honestly think it’s one of his best films from this period, and as beautiful an example of “pure cinema” as any film in Hitchcock’s body of work.

I don’t think it’s an accident that this was Hitchcock’s first collaboration with Robert Burks, the cinematographer who worked with Hitchcock into the 1960s and who shot nearly all of his most acclaimed color films, like Vertigo (1958) and North by Northwest (1959).

Strangers on a Train has a nifty little plot (based on a novel by Patricia Highsmith), but it’s the way the story is told visually and rhythmically that makes it such a tremendous thriller. From the opening scene, which cross-cuts between two passengers’ legs walking swiftly through a busy train station, we are in the hands of a master filmmaker.

One of the men is conservatively dressed, while the other wears loud shoes and pin-striped trousers. They finally take their seats on the train, cross their legs, bump into each other, pardon themselves, and then the fun begins.

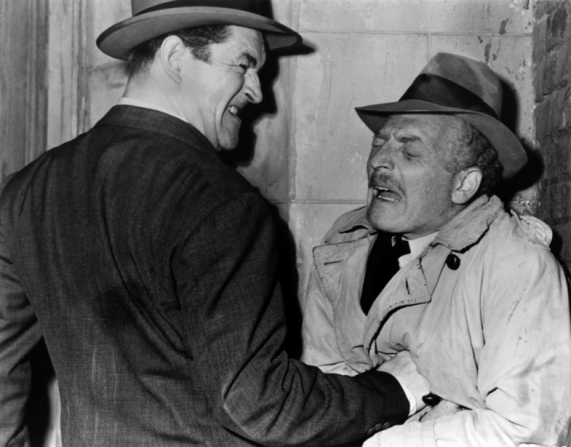

Farley Granger plays a professional tennis player named Guy Haines and Robert Walker plays an unhinged man named Bruno Antony.

The film starts with an unpleasant scenario we can all relate to — being cornered on public transportation by a chatty and overly familiar stranger — and quickly devolves into a nightmare when Bruno devises a plan in which he and Guy could commit murder for each other, getting rid of troublesome people in their lives while giving each other perfect alibis.

Guy thinks it’s just one more outlandish utterance from his very odd traveling companion, but he quickly learns how deadly serious the insane Bruno really is.

Most of the criticism I’ve seen of Strangers on a Train focuses on how much people dislike the film’s central romantic couple, played by Farley Granger and Ruth Roman, but I honestly don’t understand this.

I think Granger, while not the most interesting actor, is perfectly cast as an attractive young man completely out of his depth. And while Ruth Roman is pretty dull in this role, the scenes in which only she and Granger are on screen together occupy mere minutes of the film’s running time. Most of their scenes together also feature her hilariously dry father, a senator played by Leo G. Carroll, and her crime-obsessed sister played by Patricia Hitchcock (the director’s daughter), whose ghoulish interest in all things dark and sordid recalls the true-crime buffs in Hitchcock’s Shadow of a Doubt (1943).

Strangers on a Train is a first-class thriller with some of the most striking black & white visuals in Hitchcock’s career, as well as one of the most memorable and drawn-out murder set pieces in his body of work. It’s a terrific film, and worth revisiting if your memories of it are less than stellar.