The Body Snatcher (1945)

Directed by Robert Wise

RKO Radio Pictures

The Body Snatcher is based on Scottish author Robert Louis Stevenson’s short story of the same name, which was first published in December 1884. Stevenson’s story was inspired by a crime well-known to Scots to this day; the Burke and Hare murders. Burke and Hare were two Irish immigrants who sold corpses to Dr. Robert Knox for use in his dissection experiments in 1827 and 1828, and were symptomatic of a time when scientific curiosity was outpacing social and religious squeamishness. Prior to the Anatomy Act 1832, the only bodies that doctors could legally dissect were those of executed criminals. There were simply not enough executed criminals to fill the needs of medical schools, however, especially with the decline in executions in the early 19th century, so doctors and anatomy students frequently turned to sellers of corpses on the black market. Most of these sellers simply dug up freshly buried bodies, but Burke and Hare went an extra step, saving time by smothering people to death and selling their bodies. In the film, set in Edinburgh in 1831, the “Dr. K.” of the story becomes Dr. Wolfe MacFarlane (played by Henry Daniell), a respected surgeon who relies on the ghoulish cabman John Gray (played by Boris Karloff) to provide him with the corpses he needs to experiment on before he can cure crippling ailments. In a typical move for a film of this time, there is also a blandly handsome young doctor (played by Russell Wade), who adds little to the proceedings, merely existing to show the idealistic, humane, and optimistic face of medicine. The meat of the film is the twisted and symbiotic relationship between Gray and Dr. MacFarlane, whom Gray constantly calls “Toddy,” an old nickname that the doctor hates.

The Body Snatcher was produced by Val Lewton, who is one of the few producers to have survived the advent of the Auteur theory and emerge better remembered than many of the men who directed his films. A novelist, screenwriter, and producer, Lewton was a talented purveyor of horror and dread. He methods were suggestion and atmosphere, and he avoided cheap shocks and grotesque makeup. His monsters didn’t look like monsters, and the terror his films conveyed was largely psychological. And when horrific events did occur in his films, they did so mostly off screen. They delivered chills through the power of suggestion, and occasionally a stream of blood flowing under a door.

Prior to making The Body Snatcher, which was directed by Robert Wise, Lewton had a string of low-budget horror hits for RKO, all of which are currently available on DVD and are considered minor classics; Cat People (1942, directed by Jacques Tourneur), I Walked With a Zombie (1943, dir. Jacques Tourneur), The Leopard Man (1943, dir. Jacques Tourneur), The Seventh Victim (1943, dir. Mark Robson), The Ghost Ship (1943, dir. Mark Robson), and The Curse of the Cat People (1944, dir. Gunther von Fritsch and Robert Wise), which was originally supposed to be called Amy and Her Friend, and has only a tangential connection to the original Cat People. He had also produced two non-horror films, Mademoiselle Fifi (1944, dir. Robert Wise) and Youth Runs Wild (1944, dir. Mark Robson).

Lewton was under a few strict edicts from RKO when making his famous horror films; each had to come in at under 80 minutes long, each had to cost no more than $150,000, and the title of each would be provided by Lewton’s supervisors, which could explain why an intelligent, understated, and artful film like I Walked With a Zombie has the lurid title that it does. After the success of Cat People, however, which was made for $134,000 and grossed nearly $4 million, the studio interfered little with Lewton’s scripts and productions, generally allowing him to make exactly the kind of picture he wanted, as long as he brought it in under budget. I’ve felt for a long time that Lewton, who was a mostly unsuccessful novelist and journalist before he got into the movie business, felt as if he was better than the cheapjack films he produced. He may have been a master of the power of suggestion, but sometimes his films just feel too removed from the world of horror that they depict. I’m not saying that Lewton’s pictures would be better if they were awash in blood and guts, but sometimes they feel clinical and distant.

Along with I Walked With a Zombie, The Body Snatcher is one of my favorite Lewton pictures, due in no small part to Karloff’s brilliant performance. While the film itself can be stagy, Karloff’s performance is not. Each line he speaks drips with malevolence, while still showing the twisted humanity hidden somewhere deep inside. Gray is a man past redemption. One of the first things he does in the film is use a shovel to kill a little dog who is guarding its young master’s grave. That Karloff can create a somewhat sympathetic character from what he’s given is nothing short of phenomenal. I can think of few actors who are able to do what Karloff does with monstrous characters. (Anthony Hopkins in The Silence of the Lambs is the only person who immediately springs to mind.) Part of the success of Karloff’s performance lies in its nuances. He interacts with nearly every character in the film–Dr. MacFarlane, his young assistant, a little crippled girl (played by Sharyn Moffett), a pathetic servant named Joseph (played by Bela Lugosi)–and is a subtly different person in each scene.

The Clock is the first film Judy Garland made in which she did not sing. She had specifically requested to star in a dramatic role, since the strenuous shooting schedules of lavish musicals were beginning to fray her nerves. Producer Arthur Freed approached her with the script for The Clock (also known as Under the Clock), which was based on an unpublished short story by Paul and Pauline Gallico. Originally Fred Zinnemann was set to direct, but Garland felt they had no chemistry, and she was disappointed by early footage. Zinnemann was removed from the project, and she requested that Vincente Minnelli be brought in to direct.

The Clock is the first film Judy Garland made in which she did not sing. She had specifically requested to star in a dramatic role, since the strenuous shooting schedules of lavish musicals were beginning to fray her nerves. Producer Arthur Freed approached her with the script for The Clock (also known as Under the Clock), which was based on an unpublished short story by Paul and Pauline Gallico. Originally Fred Zinnemann was set to direct, but Garland felt they had no chemistry, and she was disappointed by early footage. Zinnemann was removed from the project, and she requested that Vincente Minnelli be brought in to direct. Mary Beth Hughes appeared in dozens of films from 1939 onward as a second- or third-billed actress (including films in the Charlie Chan, Cisco Kid, and Michael Shayne series), but in director Sam Newfield’s P.R.C. production The Lady Confesses she gets to strut her limited but charming stuff in a lead role. A natural redhead, Hughes usually appeared onscreen as a platinum blonde. Her round cheeks, big eyes, and moxie made up for what she lacked as a thespian.

Mary Beth Hughes appeared in dozens of films from 1939 onward as a second- or third-billed actress (including films in the Charlie Chan, Cisco Kid, and Michael Shayne series), but in director Sam Newfield’s P.R.C. production The Lady Confesses she gets to strut her limited but charming stuff in a lead role. A natural redhead, Hughes usually appeared onscreen as a platinum blonde. Her round cheeks, big eyes, and moxie made up for what she lacked as a thespian. French director Jean Renoir directed this adaptation of George Sessions Perry’s novel Hold Autumn in Your Hand, which won the first National Book Award in 1941. (The novel was adapted by screenwriter Hugo Butler, with uncredited contributions from Nunnally Johnson and William Faulkner.)

French director Jean Renoir directed this adaptation of George Sessions Perry’s novel Hold Autumn in Your Hand, which won the first National Book Award in 1941. (The novel was adapted by screenwriter Hugo Butler, with uncredited contributions from Nunnally Johnson and William Faulkner.) On August 8, 1944, The Hollywood Reporter announced that director Kurt Neumann was looking for 48 athletic, six-feet tall women to portray Amazons in the next Tarzan movie.

On August 8, 1944, The Hollywood Reporter announced that director Kurt Neumann was looking for 48 athletic, six-feet tall women to portray Amazons in the next Tarzan movie. James Cagney made a big splash in William A. Wellman’s The Public Enemy (1931). It was his first starring role. Some people claim that when Cagney first walked on screen in that picture, it was the beginning of “modern acting.” Whether or not you believe that claim, there’s no denying the impact Cagney had on Hollywood, especially gangster films. The scene in which he shoves a grapefruit half into Mae Clarke’s face is iconic. Late in his life, Cagney claimed that people still sent grapefruits to his table in restaurants, with a wink and a nod. The Public Enemy ushered in a new era of onscreen violence, and an icon was born.

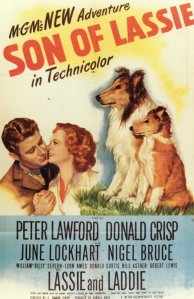

James Cagney made a big splash in William A. Wellman’s The Public Enemy (1931). It was his first starring role. Some people claim that when Cagney first walked on screen in that picture, it was the beginning of “modern acting.” Whether or not you believe that claim, there’s no denying the impact Cagney had on Hollywood, especially gangster films. The scene in which he shoves a grapefruit half into Mae Clarke’s face is iconic. Late in his life, Cagney claimed that people still sent grapefruits to his table in restaurants, with a wink and a nod. The Public Enemy ushered in a new era of onscreen violence, and an icon was born. Son of Lassie could just as easily have been called Laddie Goes to War! In this follow-up to Lassie Come Home (1943), which starred Roddy McDowall and Elizabeth Taylor, Lassie has a son, named Laddie. Laddie grows ups, as does young Joe Carraclough, who was played by McDowall in the first film, but is here replaced by future Rat Pack member and Kennedy spouse Peter Lawford, whose slightly deformed arm kept him out of World War II. Joe joins the army, and Laddie tries to join up with him, but he cringes the first time blank cartridges are fired at his face, which disqualifies him as a canine soldier. When Joe is taken prisoner of war in Norway, however, Laddie … well, I don’t want to give anything away. (But if you’ve ever seen a “boy and his dog” movie before, you can probably predict what will happen.)

Son of Lassie could just as easily have been called Laddie Goes to War! In this follow-up to Lassie Come Home (1943), which starred Roddy McDowall and Elizabeth Taylor, Lassie has a son, named Laddie. Laddie grows ups, as does young Joe Carraclough, who was played by McDowall in the first film, but is here replaced by future Rat Pack member and Kennedy spouse Peter Lawford, whose slightly deformed arm kept him out of World War II. Joe joins the army, and Laddie tries to join up with him, but he cringes the first time blank cartridges are fired at his face, which disqualifies him as a canine soldier. When Joe is taken prisoner of war in Norway, however, Laddie … well, I don’t want to give anything away. (But if you’ve ever seen a “boy and his dog” movie before, you can probably predict what will happen.) Edgar G. Ulmer was born in 1904 in Olmütz, Moravia, Austria-Hungary (now part of the Czech Republic). Like a number of talented German and Austrian directors, he moved to the United States in the ’20s and began working in Hollywood. Unlike better-known directors like Billy Wilder or Fritz Lang, however, Ulmer toiled in obscurity for most of his career, cranking out no-budget films. At least part of this was due to the fact that he was blackballed after he had an affair with Shirley Castle, who was the wife of B-picture producer Max Alexander, a nephew of powerful Universal president Carl Laemmle. Castle divorced Alexander and married Ulmer (becoming Shirley Ulmer), but the damage to Ulmer’s career was done. He spent most of the rest of his career churning out product for P.R.C. (Producers Releasing Corporation) Studios, one of the financially strapped Hollywood studios collectively referred to as “Poverty Row.”

Edgar G. Ulmer was born in 1904 in Olmütz, Moravia, Austria-Hungary (now part of the Czech Republic). Like a number of talented German and Austrian directors, he moved to the United States in the ’20s and began working in Hollywood. Unlike better-known directors like Billy Wilder or Fritz Lang, however, Ulmer toiled in obscurity for most of his career, cranking out no-budget films. At least part of this was due to the fact that he was blackballed after he had an affair with Shirley Castle, who was the wife of B-picture producer Max Alexander, a nephew of powerful Universal president Carl Laemmle. Castle divorced Alexander and married Ulmer (becoming Shirley Ulmer), but the damage to Ulmer’s career was done. He spent most of the rest of his career churning out product for P.R.C. (Producers Releasing Corporation) Studios, one of the financially strapped Hollywood studios collectively referred to as “Poverty Row.” The western genre may be moribund, but it refuses to kick the bucket. Singing cowboys, on the other hand, are deader than vaudeville. There was a time, however, when Gene Autry and Roy Rogers were two of the biggest film stars in America.

The western genre may be moribund, but it refuses to kick the bucket. Singing cowboys, on the other hand, are deader than vaudeville. There was a time, however, when Gene Autry and Roy Rogers were two of the biggest film stars in America.