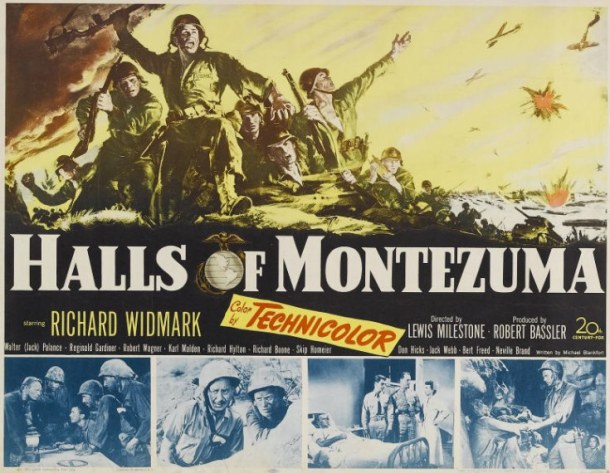

Halls of Montezuma (1951)

Directed by Lewis Milestone

20th Century-Fox

The American public never really loses its appetite for war movies, it just gets full sometimes and needs to take a nap. That was the situation in 1950. After a few impressive World War II movies were released in 1949, like Battleground and Twelve O’Clock High, the only World War II movie I can think of from 1950 that wasn’t a comedy, or a postwar drama like Fred Zinnemann’s The Men, was Fritz Lang’s American Guerrilla in the Philippines.

But the beginning of 1951 saw several war movies hit American movie theaters. Within a month of the premiere of Halls of Montezuma, at least two more war films were released; Operation Pacific, a film about World War II submarine warfare starring John Wayne, and Samuel Fuller’s The Steel Helmet, the first film about the Korean War.

No matter which war a film depicts, it’s always going to reflect the time when it was made. So while The Steel Helmet might have been the first film to explicitly depict the Korean conflict, the specter of that war hangs over Halls of Montezuma.

Like Battleground and Twelve O’Clock High, Halls of Montezuma is largely about the terrible toll of combat — what used to be called “shell shock” or “battle fatigue” and what is commonly called “PTSD” today.

Halls of Montezuma stars Richard Widmark as Anderson, a former schoolteacher who is now a lieutenant in the Marine Corps. He suffers from crippling psychosomatic migraines, and his only relief comes when he gets another little white pill from Doc (Karl Malden).

When the film begins, Lt. Anderson is tired of death. He led a company of Marines through the bloody battles of Tarawa and Iwo Jima, and only seven men in his original command are still alive. (Halls of Montezuma might be meant to depict the battle on Okinawa, but I don’t think it’s ever directly stated where it takes place.)

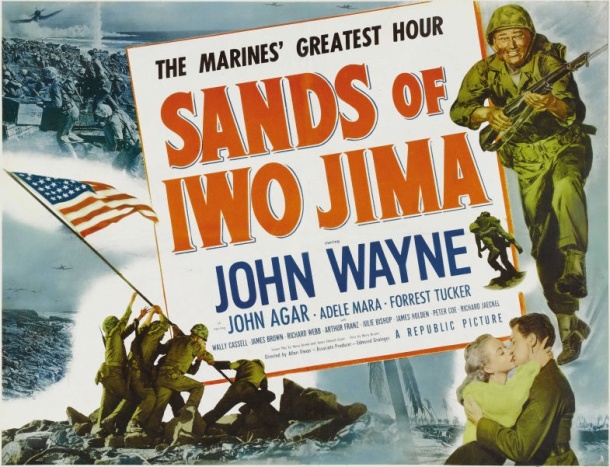

Just like Allan Dwan’s Sands of Iwo Jima (1949), Halls of Montezuma integrates real footage of the war. Unlike Sands of Iwo Jima, the documentary footage in Halls of Montezuma is in color to match the Technicolor of the film, and while it often looks spectacular, it always took me out of the narrative, which is the same problem I had with Sands of Iwo Jima.

For instance, early in the film there’s a scene where the Marines are blasting Japanese sniper’s nests and pillboxes with tank-mounted flamethrowers. Lt. Anderson gives a command into his radio, “Spray the whole hill, it’s lousy with Nips.” We see huge arcs of fire hitting a ridge, then real footage of a (presumably Japanese) soldier running, his body on fire. Halls of Montezuma is an impressively staged film, but nothing in it can quite pass for reality when laid side-by-side with documentary footage.

I’m sure that some of my recognition of the fakery of the film is based on the passage of time. In Bosley Crowther’s review of Halls of Montezuma in the January 6, 1951, issue of The New York Times, he praised the film’s documentary realism and called it “A remarkably real and agonizing demonstration of the horribleness of war, with particular reference to its impact upon the men who have to fight it on the ground.” After enough time passes it’s easier to see how a movie has been constructed. No matter how “agonizingly real” a film might look at the time of its release, it just won’t fool anyone 64 years later.

Lewis Milestone also directed All Quiet on the Western Front (1930), about the First World War, and A Walk in the Sun (1945), about American soldiers fighting in Italy during World War II. Halls of Montezuma is similar in some ways to A Walk in the Sun, including the use of occasional voiceover narration to tell the audience what various characters are thinking.

Halls of Montezuma is an earnest and well-made war movie, but it had too many clichés and inauthentic moments for me to call it a great war movie.

The interior sets look like sets, too many of the exteriors look like Southern California (which they are), the Japanese soldiers don’t look Japanese, and too many of the characters seem like “types” rather than real people, like the British interpreter played by Reginald Gardiner or the sadistic and gun-crazy punk “Pretty Boy,” played by Skip Homeier.

There are some great performances in Halls of Montezuma, though. Widmark is completely convincing as a battle-weary officer, and Richard Boone (in his first feature film role) is brilliant as Lt. Col. Gilfillan. When he asks combat correspondent Dickerman (Jack Webb) if he can fire an M1 Garand and then sends him out on a mission to take Japanese prisoners, Boone says with resignation, “I suppose I’ll be the villain of your great American war novel.” It’s one of those moments that would seem too “written” coming from another actor, but Boone sells it.