Here’s the countdown of my 10 favorite films from 1949.

Agree? Disagree? Leave a comment…

10. The Window

Ted Tetzlaff’s The Window is a film noir version of “the boy who cried wolf” in which no one believes a boy who claims to have witnessed a murder. The Window is a wonderful suspense thriller with great performances all around.

In Joseph L. Mankiewicz’s A Letter to Three Wives, a trio of women nervously wait to find out which of their husbands has run away with the town hussy. Told mostly in flashback, it’s one of the smartest and funniest films I’ve seen from the 1940s about marriage and the American class structure.

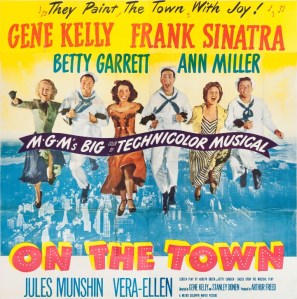

8. On the Town

Frank Sinatra and Gene Kelly’s third all-singing, all-dancing collaboration is the enduring classic of the bunch. On the Town is a joyful, whirlwind journey through New York City about three sailors with 24 hours of shore leave who paint the town red.

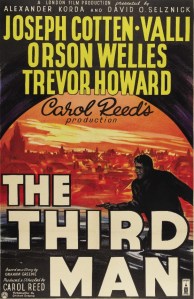

Director Carol Reed’s second collaboration with writer Graham Greene stars Joseph Cotten as a writer lost in a labyrinth of secrets and lies in postwar Vienna. Orson Welles has a relatively small amount of screen time, but his character dominates the film like a specter. The Third Man is a haunting, beautifully filmed thriller.

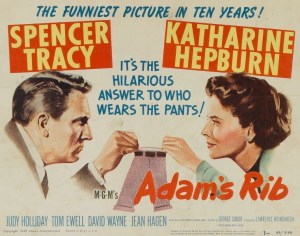

6. Adam’s Rib

It’s hard to imagine a better vehicle for the talents of Spencer Tracy and Katharine Hepburn than Adam’s Rib, a hilarious comedy written by Garson Kanin and Ruth Gordon whose take on the war between the sexes is still relevant.

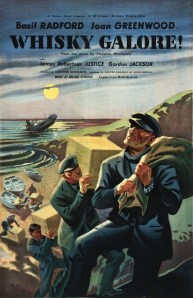

Whisky Galore is a hilarious British film about a group of islanders who “liberate” hundreds of cases of liquor from a shipwreck. It’s a great film that wrings humor out of more than just forced sobriety and drunken revelry. It’s an extremely well-crafted film about small-town life that’s warm and deeply human.

4. Stray Dog

Akira Kurosawa’s police procedural Stray Dog is the tale of an older, experienced detective (Takashi Shimura) and a younger, more impulsive detective (Toshirô Mifune) on the trail of the younger detective’s stolen pistol, which is being used in a series of increasingly violent crimes. It’s one of Kurosawa’s earliest masterpieces, and a film I can watch over and over.

3. White Heat

Raoul Walsh’s White Heat ended the classic cycle of Warner Bros. gangster movies with speed and fury, and featured a blistering performance by James Cagney as one of Hollywood’s most memorable psychopathic criminals.

2. Late Spring

Yasujiro Ozu’s tale of a father emotionally letting go of his beloved adult daughter is beautifully filmed, wonderfully acted, and quietly devastating. Ozu is the acknowledged master of the understated Japanese domestic drama, and his films are treasures to be discovered and rediscovered.

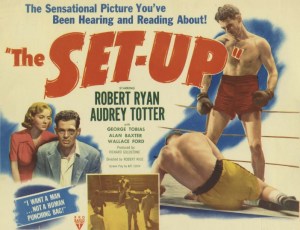

1. The Set-Up

In 1949, the Kirk Douglas vehicle Champion was the boxing movie that got all the praise, but the truly enduring classic is Robert Wise’s lean, mean The Set-Up. A masterpiece of brutal efficiency, it’s one of the all-time great noirs, without a single slack moment.

Honorable Mentions:

All the King’s Men

Battleground

Blood of the Beasts

Border Incident

Criss Cross

I Shot Jesse James

Kind Hearts and Coronets

Knock on Any Door

Mighty Joe Young

Side Street

Tension

Thieves’ Highway

Twelve O’Clock High