It has become clear to me that John Ford does something for others that he doesn’t do for me. Active from the silent era through the ’60s, Ford is regularly listed as one of the greatest American directors of all time, as well as one of the most influential.

It has become clear to me that John Ford does something for others that he doesn’t do for me. Active from the silent era through the ’60s, Ford is regularly listed as one of the greatest American directors of all time, as well as one of the most influential.

It’s not that I don’t like his films. I’ve enjoyed most that I’ve seen. But aside from The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance (1962), I haven’t loved any of them. Ford’s influence on the western is hard to overstate, and I respect what films like Stagecoach (1939) and The Searchers (1956) did to elevate the genre, but I wouldn’t count either as one of my favorite westerns.

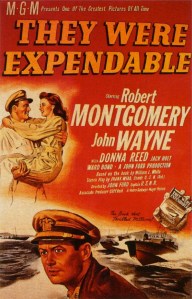

They Were Expendable was Ford’s first war movie. It is a fictionalized account of the exploits of Motor Torpedo Boat Squadron 3 in the early, disastrous days of America’s war in the Pacific. Based on the book by William L. White, the film stars Robert Montgomery as Lt. John Brickley, who believes that small, light PT (patrol torpedo) boats are the perfect crafts to use against the much-larger ships in the Japanese fleet. Despite the speed and maneuverability of PT boats, the top Naval brass reject Lt. Brickley’s plan, but he persists in equipping the boats and training his men, and they eventually launch attacks against the Japanese, and even use PT boats to evacuate Gen. Douglas MacArthur and his family when the situation in the Philippines goes from bad to worse.

They Were Expendable is a product of its time. When the actor playing MacArthur is shown (he is never named and has no lines, but it’s clear who he is supposed to be), the musical score is so overblown that it elevates MacArthur to the level of Abraham Lincoln, or possibly Jesus Christ. The bona fides of the film’s star are asserted in the credits; he is listed as “Robert Montgomery, Comdr. U.S.N.R.” (Montgomery really was a PT skipper in World War II, and did some second unit direction on the film.) And in keeping with the film’s patriotic tone, the combat efficacy of PT boats against Japanese destroyers is probably overstated. (This is also the case in White’s book, which was based solely on interviews with the young officers profiled.)

None of this was a problem for me. What was a problem was the inconsistent tone of the picture, exemplified by the two main characters. Montgomery underplays his role, but you can see the anguish behind his stoic mask. He demonstrates the value of bravery in the face of almost certain defeat. On the other hand, John Wayne, as Lt. (J.G.) “Rusty” Ryan, has swagger to spare, and is hell-bent for leather the whole time. He even finds time to romance a pretty nurse, 2nd Lt. Sandy Davyss (played by Donna Reed). Wayne doesn’t deliver a bad performance, but it’s a performance that seems better suited to a western than a film about the darkest days of America’s war against the Japanese.

Maybe we can blame Ford and Wayne’s previous work together, and their comfort with a particular genre. Reports that Ford (who served in the navy in World War II and made combat documentaries) constantly berated Wayne during the filming of They Were Expendable for not serving in the war don’t change the fact that the two men made many westerns together before this, and would make many after it. Several scenes in They Were Expendable feel straight out of a western. Determined to have an Irish wake for one of his fallen brothers, Wayne forces a Filipino bar owner to stay open, even though the bar owner is trying to escape with his family in the face of reports that the Japanese are overrunning the islands. Even more out of place is the scene in which the old shipwright who repairs the PT boats, “Dad” Knowland (Russell Simpson), refuses to leave the shack where he’s lived and worked in the Philippines since the turn of the century. Wayne eventually gives up trying to persuade him to evacuate, and leaves him on his front porch with a shotgun across his lap and a jug of moonshine next to him, as “Red River Valley” plays in the background.

The scenes of combat in They Were Expendable are well-handled, and the picture looks great. Montgomery is particularly good in his role. As war movies from the ’40s go, it’s not bad, but far from the best I’ve seen.

Abbott and Costello were one of the most popular comedy teams of the ’40s. They’re still famous for their “Who’s on first?” routine, and a lot of their film and radio work is still funny, as long as you’re in the mood for their old-fashioned brand of burlesque antics. If you’re not in the mood for them, or if one of their bits falls flat, Lou Costello is the most irritating man on earth.

Abbott and Costello were one of the most popular comedy teams of the ’40s. They’re still famous for their “Who’s on first?” routine, and a lot of their film and radio work is still funny, as long as you’re in the mood for their old-fashioned brand of burlesque antics. If you’re not in the mood for them, or if one of their bits falls flat, Lou Costello is the most irritating man on earth. I don’t generally like musicals, but I loved Anchors Aweigh. It probably doesn’t hurt that I really like both Frank Sinatra and Gene Kelly, and this movie uses both of them to wonderful effect. Kelly’s dance sequences are all high points, and even Sinatra comports himself well in the one dance in which he has to match Kelly step-for-step. Although I can only imagine how many takes it took to get it right. Unlike today’s hyperkinetic editing styles, most of the dance sequences in Anchors Aweigh are done in what appear to be one take, or just a few at most.

I don’t generally like musicals, but I loved Anchors Aweigh. It probably doesn’t hurt that I really like both Frank Sinatra and Gene Kelly, and this movie uses both of them to wonderful effect. Kelly’s dance sequences are all high points, and even Sinatra comports himself well in the one dance in which he has to match Kelly step-for-step. Although I can only imagine how many takes it took to get it right. Unlike today’s hyperkinetic editing styles, most of the dance sequences in Anchors Aweigh are done in what appear to be one take, or just a few at most. The Clock is the first film Judy Garland made in which she did not sing. She had specifically requested to star in a dramatic role, since the strenuous shooting schedules of lavish musicals were beginning to fray her nerves. Producer Arthur Freed approached her with the script for The Clock (also known as Under the Clock), which was based on an unpublished short story by Paul and Pauline Gallico. Originally Fred Zinnemann was set to direct, but Garland felt they had no chemistry, and she was disappointed by early footage. Zinnemann was removed from the project, and she requested that Vincente Minnelli be brought in to direct.

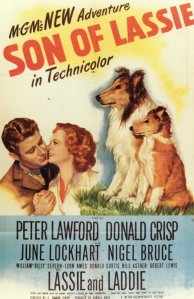

The Clock is the first film Judy Garland made in which she did not sing. She had specifically requested to star in a dramatic role, since the strenuous shooting schedules of lavish musicals were beginning to fray her nerves. Producer Arthur Freed approached her with the script for The Clock (also known as Under the Clock), which was based on an unpublished short story by Paul and Pauline Gallico. Originally Fred Zinnemann was set to direct, but Garland felt they had no chemistry, and she was disappointed by early footage. Zinnemann was removed from the project, and she requested that Vincente Minnelli be brought in to direct. Son of Lassie could just as easily have been called Laddie Goes to War! In this follow-up to Lassie Come Home (1943), which starred Roddy McDowall and Elizabeth Taylor, Lassie has a son, named Laddie. Laddie grows ups, as does young Joe Carraclough, who was played by McDowall in the first film, but is here replaced by future Rat Pack member and Kennedy spouse Peter Lawford, whose slightly deformed arm kept him out of World War II. Joe joins the army, and Laddie tries to join up with him, but he cringes the first time blank cartridges are fired at his face, which disqualifies him as a canine soldier. When Joe is taken prisoner of war in Norway, however, Laddie … well, I don’t want to give anything away. (But if you’ve ever seen a “boy and his dog” movie before, you can probably predict what will happen.)

Son of Lassie could just as easily have been called Laddie Goes to War! In this follow-up to Lassie Come Home (1943), which starred Roddy McDowall and Elizabeth Taylor, Lassie has a son, named Laddie. Laddie grows ups, as does young Joe Carraclough, who was played by McDowall in the first film, but is here replaced by future Rat Pack member and Kennedy spouse Peter Lawford, whose slightly deformed arm kept him out of World War II. Joe joins the army, and Laddie tries to join up with him, but he cringes the first time blank cartridges are fired at his face, which disqualifies him as a canine soldier. When Joe is taken prisoner of war in Norway, however, Laddie … well, I don’t want to give anything away. (But if you’ve ever seen a “boy and his dog” movie before, you can probably predict what will happen.)