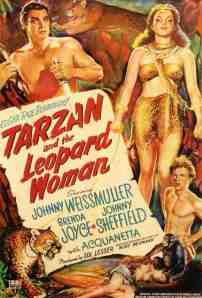

A lot of fans of Johnny Weissmuller’s work as Tarzan in the MGM series of the ’30s like to beat up on the RKO Radio Pictures Tarzan pictures of the ’40s. They’re campier, the production values are cheaper, and Weissmuller was older when he made them. I say, so what? They’re still great Saturday-matinee entertainment, especially this one. Tarzan and the Leopard Woman moves at a good pace, it’s loony without being over-the-top, and Weissmuller is in better shape than he was in the previous few entries in the series.

A lot of fans of Johnny Weissmuller’s work as Tarzan in the MGM series of the ’30s like to beat up on the RKO Radio Pictures Tarzan pictures of the ’40s. They’re campier, the production values are cheaper, and Weissmuller was older when he made them. I say, so what? They’re still great Saturday-matinee entertainment, especially this one. Tarzan and the Leopard Woman moves at a good pace, it’s loony without being over-the-top, and Weissmuller is in better shape than he was in the previous few entries in the series.

Weissmuller was a big guy; 6’3″ and 190 pounds in his prime. Like a lot of athletes, he had a tendency to gain weight when he wasn’t competing professionally (when he was making the Jungle Jim series in the ’50s, he was reportedly fined $5,000 for every pound he was overweight). In Tarzan and the Leopard Woman, however, he was 41 years old, and looked better than he had in years. His face looks older and his eyes are a little pouchy, but three divorces (including one from the physically abusive Lupe Velez) will do that do a guy. Even though he was nearing middle age when he made this picture, Weissmuller was still a sight to behold. When he jumps into a river to save four winsome Zambesi maidens (played by Iris Flores, Helen Gerald, Lillian Molieri, and Kay Solinas) from crocodiles, he knifes through the water, and it’s not hard to see why he won five Olympic gold medals for swimming, and was the first man to swim the 100-meter freestyle in less than a minute.

When Tarzan and the Leopard Woman begins, the local commissioner (Dennis Hoey) is speaking to Dr. Ameer Lazar (Edgar Barrier), a native who has been educated and “civilized.” The commissioner is concerned about a spate of attacks by what seem to be leopards. Dr. Lazar appears to share his concern, but we soon learn that Lazar is a wolf in sheep’s clothing. Privately he spouts anti-Western doctrine that sounds suspiciously like Marxism, and is the leader of a tribe of men who worship leopards and wear their skins. Tarzan believes that the “leopard” attacks are really the work of men, so to throw off suspicion, Lazar releases a trio of actual leopards as cannon fodder. Their attack against the caravan is repelled, the leopards are killed, and everyone is satisfied that the terror has passed. Everyone, that is, except Tarzan, who still smells a rat.

The original shooting title of Tarzan and the Leopard Woman was Tarzan and the Leopard Men, which is probably a more accurate title, but definitely a less sexy one, especially once you see the leopard men. The eponymous leopard woman is Dr. Lazar’s sister, Lea, high priestess of the leopard cult. Played by the exotic-looking actress Acquanetta, Lea makes a few memorable appearances in the beginning of the film with her voluptuous breasts barely concealed behind a gauzy wrap, but after the halfway mark she wears a more concealing leopard-print dress, and spends most of her time standing on an altar, goading on the leopard men’s dastardly acts. For the most part, the leopard men are paunchy, pigeon-chested, middle-aged men whose poorly choreographed ritual “dancing” never stops being unintentionally hilarious.

Acquanetta was born Mildred Davenport in Ozone, Wyoming, in 1921. She changed her name to “Burnu Acquanetta,” then to just “Acquanetta,” and starred in films like Rhythm of the Islands (1943), Captive Wild Woman (1943), and Jungle Woman (1944). The raison d’être of most island pictures and jungle movies in the ’40s was to show a whole lot more skin than was considered appropriate in any other genre of the ’40s, and on that count, Tarzan and the Leopard Woman succeeds. Weissmuller’s loincloth is as skimpy as it ever was, and the scene in which he’s scratched all over by the leopard men’s metal claws, then tied tightly to a pillar and menaced by Lea surely excited plenty of future little sadomasochists in the audience.

Former model Brenda Joyce, in her second outing as Jane, has really grown into the role, and looks great. I missed Maureen O’Sullivan when she left the franchise, but Joyce has really grown on me since Tarzan and the Amazons (1945). She’s pretty and charming, not to mention stacked.

There’s a subplot in Tarzan and the Leopard Woman that I’m going to call “Battle of the Boys.” Johnny Sheffield is still playing Tarzan and Jane’s adopted son, “Boy,” but he’s quickly outgrowing the moniker. Sheffield was 14 when he made this film, but he looks older. Unlike a lot of cute child stars to whom puberty was unkind, Sheffield looks like he’s in better shape than anyone else in the movie, and he’s good-looking. Unfortunately, the same cannot be said for Tommy Cook, who’s a year older than Sheffield, but looks younger and weirder. The last time I saw Cook, he played the cute little sidekick named “Kimbu” in the 1941 Republic serial The Jungle Girl. Here, in an enormous thespic stretch, he plays Lea’s younger brother “Kimba,” who insinuates himself into the lives of Tarzan, Jane, and Boy. He might as well have been named “Bad Boy,” since he’s Boy’s evil doppelgänger. Jane takes pity on Kimba and cares for him, but his true intention is to cut out her heart in order to become a full-fledged warrior among the leopard men.

I don’t think I’ll be giving anything away if I say that Tarzan, Jane, Boy, and their pet chimp Cheetah make it through the proceedings relatively unscathed, while the bad guys all die horrible, gruesome deaths. Tarzan and the Leopard Woman might not be the greatest entry in the Tarzan franchise, but it’s far from the worst, and packs plenty of action and thrills into its 72-minute running time.

Republic Pictures is the unassailable king of the cliffhangers after the silent era. Most of the best chapterplays of the ’30s and ’40s were Republic productions. Dick Tracy (1937), The Lone Ranger (1938), Zorro’s Fighting Legion (1939), Adventures of Red Ryder (1940), Mysterious Doctor Satan (1940), Adventures of Captain Marvel (1941), Jungle Girl (1941), Spy Smasher (1942), Perils of Nyoka (1942), The Masked Marvel (1943), and Captain America (1944) are just a few of the more than sixty serials produced by Republic Pictures, most of which are still incredibly entertaining. The best Republic serials combined wild action and elaborate stunts with nicely paced stories that could be strung out over 12 to 15 weekly installments with a few subplots here and there, but nothing too complicated or that viewers couldn’t pick up with in the middle. Each chapter ended with a cliffhanger (like Captain Marvel flying toward a woman falling off a dam, or a wall of fire rushing down a tunnel toward Spy Smasher). The next week’s chapter would begin with a minute or two of the previous week’s climax and the resolution, and the cycle would repeat until the final chapter.

Republic Pictures is the unassailable king of the cliffhangers after the silent era. Most of the best chapterplays of the ’30s and ’40s were Republic productions. Dick Tracy (1937), The Lone Ranger (1938), Zorro’s Fighting Legion (1939), Adventures of Red Ryder (1940), Mysterious Doctor Satan (1940), Adventures of Captain Marvel (1941), Jungle Girl (1941), Spy Smasher (1942), Perils of Nyoka (1942), The Masked Marvel (1943), and Captain America (1944) are just a few of the more than sixty serials produced by Republic Pictures, most of which are still incredibly entertaining. The best Republic serials combined wild action and elaborate stunts with nicely paced stories that could be strung out over 12 to 15 weekly installments with a few subplots here and there, but nothing too complicated or that viewers couldn’t pick up with in the middle. Each chapter ended with a cliffhanger (like Captain Marvel flying toward a woman falling off a dam, or a wall of fire rushing down a tunnel toward Spy Smasher). The next week’s chapter would begin with a minute or two of the previous week’s climax and the resolution, and the cycle would repeat until the final chapter. The first film serial featuring Secret Agent X-9 was made by Universal in 1937, and starred Scott Kolk as Agent X-9, a.k.a. “Dexter,” who sought to recover the crown jewels of Belgravia from a master thief called “Blackstone.” The second featured a boyish-looking 32-year-old Lloyd Bridges as Agent X-9, a.k.a. “Phil Corrigan.” Made toward the end of World War II, the 1945 iteration of the character focused on wartime intrigue and Corrigan’s cat-and-mouse games with Axis spies. Taking a cue from Casablanca (1942), the serial was set in a neutral country called “Shadow Island,” in which Americans, Japanese, Chinese, French, Germans, Australians, and the seafaring riffraff of the world freely intermingle. A fictional island nation off the coast of China, “Shadow Island” has a de facto leader named “Lucky Kamber” (Cy Kendall) who owns a bar called “House of Shadows” and has a finger in every pie, including gambling and espionage. Various German and Japanese military officers, secret agents, and thugs run amuck in this serial, but the one who most stands out is the unfortunately made-up and attired Victoria Horne as “Nabura.” In her role as a Japanese spymaster, Horne is outfitted with eyepieces that cover her upper eyelids, appearing to drag them down from sheer weight. She doesn’t look Asian, she just looks as if her eyes are closed.

The first film serial featuring Secret Agent X-9 was made by Universal in 1937, and starred Scott Kolk as Agent X-9, a.k.a. “Dexter,” who sought to recover the crown jewels of Belgravia from a master thief called “Blackstone.” The second featured a boyish-looking 32-year-old Lloyd Bridges as Agent X-9, a.k.a. “Phil Corrigan.” Made toward the end of World War II, the 1945 iteration of the character focused on wartime intrigue and Corrigan’s cat-and-mouse games with Axis spies. Taking a cue from Casablanca (1942), the serial was set in a neutral country called “Shadow Island,” in which Americans, Japanese, Chinese, French, Germans, Australians, and the seafaring riffraff of the world freely intermingle. A fictional island nation off the coast of China, “Shadow Island” has a de facto leader named “Lucky Kamber” (Cy Kendall) who owns a bar called “House of Shadows” and has a finger in every pie, including gambling and espionage. Various German and Japanese military officers, secret agents, and thugs run amuck in this serial, but the one who most stands out is the unfortunately made-up and attired Victoria Horne as “Nabura.” In her role as a Japanese spymaster, Horne is outfitted with eyepieces that cover her upper eyelids, appearing to drag them down from sheer weight. She doesn’t look Asian, she just looks as if her eyes are closed.