Roy William Neill’s The Woman in Green is the eleventh film Basil Rathbone and Nigel Bruce made together in which they played Sherlock Holmes and Dr. Watson, respectively. It’s perhaps not the best in the series, but it presents an excellent mystery, and offers everything fans of the previous Sherlock Holmes films will look for. There are gruesome yet puzzling clues, a pretty young woman who comes to Holmes for help, a bewitching femme fatale, a clever blackmailing scheme that involves hypnosis, and Professor Moriarty behind it all.

Roy William Neill’s The Woman in Green is the eleventh film Basil Rathbone and Nigel Bruce made together in which they played Sherlock Holmes and Dr. Watson, respectively. It’s perhaps not the best in the series, but it presents an excellent mystery, and offers everything fans of the previous Sherlock Holmes films will look for. There are gruesome yet puzzling clues, a pretty young woman who comes to Holmes for help, a bewitching femme fatale, a clever blackmailing scheme that involves hypnosis, and Professor Moriarty behind it all.

This was only the third time that Moriarty, Holmes’s archenemy and “the Napoleon of crime,” showed up in the series. The first time was in The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes (1939), when he was played by George Zucco. The second time was in Sherlock Holmes and the Secret Weapon (1943), when he was played by Lionel Atwill. Somewhat confusingly, all three men also appeared in different roles in Universal Pictures’ Sherlock Holmes series. Zucco and Daniell even appeared together as cooperating villains in Sherlock Holmes in Washington (1943). If I had my druthers, Zucco would have played Moriarty in all three films, since he’s my personal favorite, but we can’t always get what we want. And apparently Rathbone named Daniell as his favorite Moriarty, so clearly it’s just a matter of taste. Daniell was certainly one of the more dependable Hollywood villains of the ’40s. He was smooth and sophisticated with just the right touch of menace.

When The Woman in Green begins, Moriarty is presumed dead, since he is believed to have been hanged in Montevideo. Meanwhile, Holmes has his hands full in London with a series of mysterious murders. Young women are being killed, and in each case one finger is missing from the corpse. Aside from that one detail, however, there is no connection between any of the murders, and Scotland Yard can’t make heads or tails of the case. When a young woman named Maude Fenwick (Eve Amber) comes to Holmes for help, however, things start falling into place. She’s worried about her father, Sir George Fenwick (Paul Cavanagh), who has been acting very strangely ever since he took up with an alluring and mysterious woman named Lydia (Hillary Brooke). When Maude catches her father trying to bury a finger in his garden, she realizes it’s time to enlist the help of the great detective.

The way the mystery unfolds is satisfying, if somewhat fanciful. One has to suspend some disbelief in order to go along for the ride, but what else is new?

Media tie-ins are nothing new. Radio’s Boston Blackie, a long-running syndicated show about a (mostly) reformed jewel thief and amateur sleuth, got its start as a series of short stories, then silent films, then talkies, before being adapted for radio. And big-screen adaptations of radio series were commonplace. The Whistler, The Great Gildersleeve, Fibber McGee & Molly, The Green Hornet, The Lone Ranger, and I Love a Mystery all led to multiple film adaptations, not to mention the many radio series that were adapted from other media, like dime novels or the daily comic strips, that went on to be films.

Media tie-ins are nothing new. Radio’s Boston Blackie, a long-running syndicated show about a (mostly) reformed jewel thief and amateur sleuth, got its start as a series of short stories, then silent films, then talkies, before being adapted for radio. And big-screen adaptations of radio series were commonplace. The Whistler, The Great Gildersleeve, Fibber McGee & Molly, The Green Hornet, The Lone Ranger, and I Love a Mystery all led to multiple film adaptations, not to mention the many radio series that were adapted from other media, like dime novels or the daily comic strips, that went on to be films.

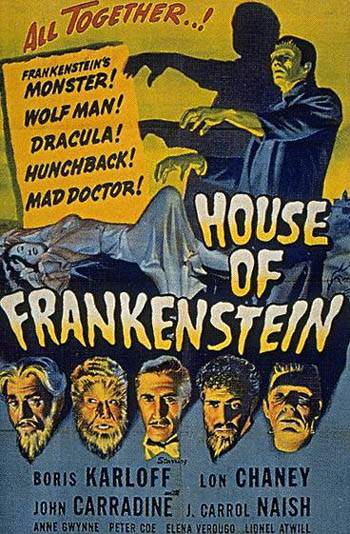

In an effort to more deeply penetrate the pop culture of the 1940s and 1950s, I’ve been listening to radio shows and watching old movies pretty much in the order they were released. I’ve been doing this for awhile, but since we have to start somewhere, we’re starting on December 1st, 1944. World War II was in full swing in both Europe and the Pacific, and a little film called House of Frankenstein was released in theaters in the United States.

In an effort to more deeply penetrate the pop culture of the 1940s and 1950s, I’ve been listening to radio shows and watching old movies pretty much in the order they were released. I’ve been doing this for awhile, but since we have to start somewhere, we’re starting on December 1st, 1944. World War II was in full swing in both Europe and the Pacific, and a little film called House of Frankenstein was released in theaters in the United States.