In the grand tradition of singing cowboys, Monte Hale plays a character in Out California Way named “Monte Hale.”

In the grand tradition of singing cowboys, Monte Hale plays a character in Out California Way named “Monte Hale.”

Out California Way is filmed in “Trucolor,” a two-color film process owned by Republic Pictures, and throws Hale into a metafictional world that pulls back the curtain and allows boys and girls at the Saturday matinée to see what might be going on behind the scenes at Republic with all of their favorite cowboy stars.

Hale doesn’t sit quite as tall in the saddle as Republic’s big boys, Gene Autry and Roy Rogers, but he’s self-effacing and charming enough to be believable when he says he’s “just a plain cowboy trying to break in” to the movies.

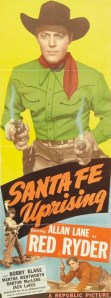

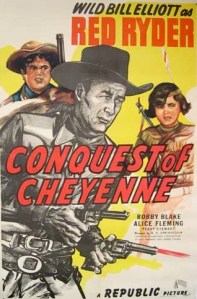

He’s assisted by little Danny McCoy (Bobby Blake, famous for playing Little Beaver in the Red Ryder series), who’s trying to get his horse Pardner into the movies.

Opposing them is the prima donna Rod Mason (John Dehner), who’s a big radio star as the “Robin Hood of the Range,” and has a career in pictures, too. Little Danny McCoy is president of the Rod Mason Fan Club, but that changes pretty fast after he actually meets the guy. Not only is Mason temperamental and nasty to his co-stars, but he hates children and animals. After threatening to whip Pardner if Danny doesn’t get him off the set, it’s clear that Danny has room in his heart for another cowboy actor. For that matter, so does his young, pretty mother, Gloria (played by Lorna Gray, who’s just 16 years older than Blake).

Hale’s an expert horse trainer, and together he and Pardner form a great team. Originally cast as stunt actors on one of Rod Mason’s pictures, they do such a good job that every rewrite comes back with a bigger role for Hale and a smaller part for Mason.

Mason and his sidekick, stunt rider Ace Hanlon (Fred Graham), are typical black hats, so they stop at nothing to foil Hale and Pardner’s success. While performing a stunt, Ace throws short-fuse dynamite at Hale that doesn’t kill him, but totally blows Pardner’s nerves.

Hale takes time off to retrain Pardner and help him over his trauma, but Mason and Ace immediately undo his hard work by sneaking into the corral at night and freaking out Pardner all over again by repeatedly firing a revolver near his head.

On his journey from “plain cowboy” to movie star, Hale is joined by special guest stars Allan Lane, Don “Red Barry,” Dale Evans, Roy Rogers, and horse Trigger, all members of Republic Pictures’ stable of western stars, and all playing themselves in the sequence in which Hale gives Gloria a tour of the studios. Roy and Dale perform a nice rendition of “Ridin’ Down the Sunset Trail” for them. Not bad for a first date.

John Dehner, who would later be a recurring actor on Gunsmoke (both the radio and TV versions), was a fine actor and makes for a great villain in this picture. While Out California Way isn’t substantively different from any of the hundreds of other oaters put out by Republic Pictures, it was fun to see a slightly different plot than the dependable old “evil land baron makes a grab for smaller ranchers’ land.”