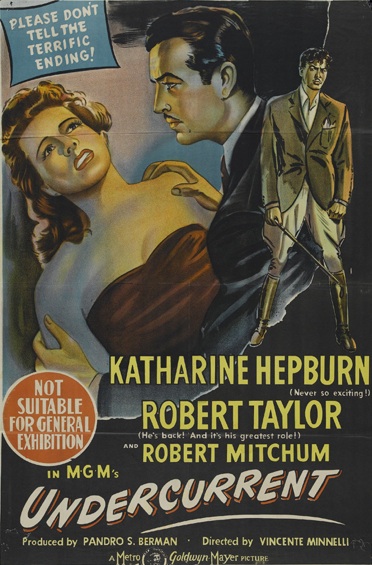

Undercurrent (1946)

Directed by Vincente Minnelli

Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer

The next time you and a friend see a turgid, overlong thriller with too many twists and turns, bogus storytelling, and good actors wasted, and your friend says, “They don’t make ’em like they used to,” you can show your friend Undercurrent and prove that they make ’em exactly like they used to.

Pound for pound, Undercurrent might have boasted more talent than any other mystery melodrama in 1946. Director Vincente Minnelli and cinematographer Karl Freund were both gifted craftsmen with numerous acclaimed films under their belts. Herbert Stothart’s music is moody and evocative, especially the film’s haunting theme. Actors Robert Taylor and Katharine Hepburn were both stars of the highest magnitude, and hadn’t been seen onscreen for some time. Taylor had just finished his term of service as a flying instructor in the U.S. Naval Air Corps and Hepburn hadn’t appeared in a movie for a year and a half.

So what’s the problem? While studio tinkering could have played some part, the problem seems to mostly be Edward Chodorov’s screenplay, which was based on a story by Thelma Strabel. In a word, it’s silly. As soon as a promising situation is established, the story goes in a different direction, which serves to undercut the tension. The review of the film in the November 11, 1946, issue of Time called the plot “indigestible,” and said it was like “a woman’s magazine serial consumed at one gulp.”

Hepburn plays a young woman named Ann Hamilton who lives with her father, chemistry professor “Dink” Hamilton (Edmund Gwenn). Ann is herself chemically inclined, and prefers to spend time tinkering in the laboratory than entertaining proposals from eligible young men. All that changes when the handsome, mustachioed, and fabulously wealthy Alan Garroway (Taylor) enters her life. Alan is the inventor of the Garroway Distance Controller, which helped win the war.

Alan and Ann marry, and he takes her away with him to Washington, D.C., where she feels completely out of her depth in high society. Meanwhile, Alan starts making sinister insinuations about his brother Michael, who supposedly went missing years earlier with a large sum of money embezzled from the family business, and who is offscreen for most of the picture. The film seems to be setting up “What happened to Michael Garroway?” as the central mystery, but if you’ve looked at a cast list with character names, this plot thread won’t be that mysterious for you.

When Alan takes Ann away to his lovely country home in Middleburg, Virginia, the film threatens to settle down and become a solid Gothic melodrama. The estate has no phone line, and Alan’s behavior is increasingly bizarre. And as one critic noted, the central theme of Gothic fiction seems to be, “Someone is trying to kill me, and I think it may be my husband.”

True to form, however, the film goes in yet another direction, with Ann going off to explore Michael Garroway’s ludicrously appointed mansion-cum-bachelor pad, where she explores his musical instruments and books of poetry with copious underlinings, and seems to be falling in love with a man she has never met. I’m sure a good film could be made about a love triangle with one-third of the equation missing for most of the film’s running time, but this isn’t it. As Bosley Crowther said in his review of Undercurrent in the November 29, 1946, issue of the NY Times, “And if that also sounds a trifle senseless, let us hasten to assure you that it is.”

Robert Mitchum — one of my favorite actors of all time, ever since I saw him host Saturday Night Live in 1987 and asked my mom, “Who is that?” — is also in Undercurrent, but he doesn’t show up until more than halfway through the film’s running time, and only has a few scenes.

I may have made Undercurrent sound terrible. It’s not. It’s mediocre popcorn entertainment, and I had fun watching it. And it’s no worse than most of the “neo-noirs” that littered multiplexes throughout the 1990s … it’s just not much better, either.

Pingback: Cry Wolf (July 18, 1947) « OCD Viewer

Pingback: High Wall (Dec. 17, 1947) « OCD Viewer

Pingback: Secret Beyond the Door (Dec. 29, 1947) « OCD Viewer

Pingback: Act of Violence (Dec. 21, 1948) | OCD Viewer