Snitches get stitches.

Snitches get stitches.

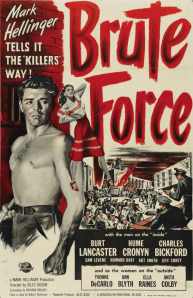

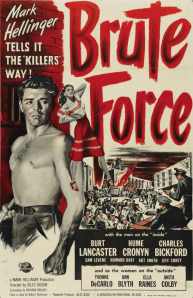

Or, in the case of Jules Dassin’s Brute Force, they get forced into a giant machine press by a group of cons wielding acetylene torches. They also get tied screaming to the front of a mining cart and used as a human shield during a massive prison break.

Westgate Penitentiary is hell on earth. All the cells are filled to double capacity. The warden is a weak-willed jellyfish who cedes all authority to the sadistic Capt. Munsey (Hume Cronyn). There are punishing make-work assignments in the dreaded “drainpipe.” Capt. Munsey plants contraband on prisoners just to send them to solitary confinement. And worst of all, on movie night the cons are forced to watch The Egg and I.

Brute Force is director Dassin’s first film noir (and still one of his best). It’s also producer Mark Hellinger’s second great film to star Burt Lancaster (the first was The Killers, in 1946).

In 1947, Lancaster wasn’t the versatile superstar he would eventually become. He was mostly known for playing “The Swede” in The Killers. The Swede was a lovesick former prizefighter; a big, dumb brute who feels pain, but little else. Brute Force allows Lancaster to stretch a little as an actor. The character he plays, Joe Collins, is the biggest, toughest man in Westgate — on the surface, not that different from The Swede — but he’s also a canny tactician who is ruthlessly efficient at getting what he wants. Collins doesn’t have a lot of dialogue, but Lancaster’s physical performance is phenomenal, and would have been at home in a silent film.

It’s a cliche to say that an actor’s body is his “instrument,” but it’s true of Lancaster, a former circus performer who expresses more with his body and his eyes in Brute Force than words ever could.

It’s a cliche to say that an actor’s body is his “instrument,” but it’s true of Lancaster, a former circus performer who expresses more with his body and his eyes in Brute Force than words ever could.

Collins is the de facto leader of the men in cell R17. He wants out of Westgate Penitentiary, but unlike all the daydreaming, hard-luck sad sacks who are behind bars with him, Collins has a plan, and it’s a good one. But for his plan to work, he has to have the support of the other five men in cell R17, as well as the cooperation and support of a hardened old convict named Gallagher (played with grumpy gravitas by the great Charles Bickford). Gallagher is up for parole, and he’s not sure if he wants to endanger his chances of release by throwing his lot in with Collins.

Brute Force is a film as lean and mean as Joe Collins himself, which makes the sentimental back stories of the convicts feel especially unnecessary. I’ve seen Brute Force at least three times now, and every time I see it I hate the flashback portions of the film more and more. I don’t think Dassin was fully committed to them either, and the abrupt tonal shifts they force on the movie are irritating and unnecessary.

They’re unnecessary because in a prison film about a sadistic captain of the guards and his unfair treatment of the prisoners, the audience will naturally identify with the prisoners without really caring about how they ended up in prison. (Imagine a flashback sequence in Cool Hand Luke that shows Paul Newman saving children from a burning orphanage — what would be the point?)

The fact that the audience knows from the outset of the film that Capt. Munsey arranged to have a shiv planted on Joe Collins in order to throw him into solitary is upsetting enough to most people’s sense of decency and fair play. We don’t also need a ridiculous subplot about Joe’s girl on the outside, Ruth (Ann Blyth), who has cancer and refuses to get the operation she needs unless Joe is with her.

The fact that the audience knows from the outset of the film that Capt. Munsey arranged to have a shiv planted on Joe Collins in order to throw him into solitary is upsetting enough to most people’s sense of decency and fair play. We don’t also need a ridiculous subplot about Joe’s girl on the outside, Ruth (Ann Blyth), who has cancer and refuses to get the operation she needs unless Joe is with her.

Ditto for the backstory of “Soldier” (Howard Duff, in his first film role — he’s listed in the opening credits as “Radio’s Sam Spade,” the role he was best known for at the time). Duff’s boyish face and incongruously deep, soothing voice do more to elicit the audience’s sympathy than the smarmy flashback in which he’s captured by MPs in Italy and falsely accused of murder while distributed food to the hungry.

Not every backstory in the film is sentimental, nor does every backstory paint its criminal protagonist in a great light. But they are all, in their own way, unnecessary. For instance, the audience doesn’t need to see the flashback in which Tom Lister (Whit Bissell) gives his wife a fur coat with money he’s embezzled to know that he’s a white collar criminal. (Although it’s always nice to see the beautiful Ella Raines, who plays his wife.) Lister’s eyeglasses, his effete appearance, and Munsey’s line — “You’re no hoodlum, like the others in this cell. Why protect them?” — tell us all we need to know about Tom Lister.

The only flashback I enjoyed and would be sad to see excised from the film is the whimsical story Spencer (John Hoyt) tells about the beautiful girl named Flossie who helped him out of a tough jam only to turn around and take off with his money. Not only is the flashback funny and mercifully brief, it ends with the wonderful line, “I wonder who Flossie’s fleecing now.”

In fairness to producer Hellinger, who was largely responsible for the flashbacks, he knew what it took to get a picture made, and how to make a picture that would lead to another picture. The top brass at Universal probably wouldn’t have been crazy about a grim prison movie with no female characters, so the backstories of the prisoners allowed for several beautiful actresses under contract with Universal to draw people into the theater. (And even though I don’t like the flashbacks, I never mind seeing the aforementioned Raines or the beautiful Yvonne De Carlo, who plays Soldier’s Italian femme fatale.)

Also, Hellinger’s skill at wheeling and dealing helped him negotiate the film’s violence around the production code, and helped Dassin get away with things other directors might not have been able to. Brute Force is an extraordinarily violent film for 1947. Of course, it doesn’t show what really happens to human bodies blasted by Thompson submachine guns or .30 caliber machine guns, but it implies enough.

I haven’t said a lot about Hume Cronyn’s performance as Capt. Munsey, and I’d be remiss if I didn’t praise him. The diminutive, soft-voiced Cronyn is one of the most memorable villains in the film noir pantheon. Cronyn gives “Napoleon complex” a whole new meaning, and he gives lines like “I get quite a kick out of censoring the mail” a creepy, sociopathic edge.

I haven’t said a lot about Hume Cronyn’s performance as Capt. Munsey, and I’d be remiss if I didn’t praise him. The diminutive, soft-voiced Cronyn is one of the most memorable villains in the film noir pantheon. Cronyn gives “Napoleon complex” a whole new meaning, and he gives lines like “I get quite a kick out of censoring the mail” a creepy, sociopathic edge.

It’s pretty clear that Dassin is using Munsey to make a statement about creeping fascism in America. Munsey is a homegrown little Hitler, and just in case you don’t immediately get the connection when Munsey professes his simplistic, Social Darwinist philosophy, Dassin drives the point home with the set design of Munsey’s office, which includes a giant framed photograph of himself, enormous shotguns that he relishes stroking and polishing, and sculptures and paintings that scream homosexual body worship, not to mention a phonograph on which he plays the overture to Wagner’s “Tannhäuser” while brutally beating a hapless inmate (Sam Levene) with a length of rubber hose for information.

Despite a few missteps here and there, Brute Force is a great film, and should be seen by anyone who appreciates prison movies, film noir, violence in the cinema, finely crafted black and white cinematography, or the brilliant film scores of Miklós Rózsa.

A note about Jules Dassin: because of his French-sounding surname, and the fact that one of his best and most well-known pictures, Rififi (1955), is a French-language film, a lot of people are under the mistaken impression that Jules Dassin was French. He wasn’t. He was an American who was born in Connecticut in 1911 to Russian-Jewish immigrant parents. He immigrated to Europe after he was blacklisted following testimony about him that was given to HUAC in 1951.

Every student of film noir knows that the genre owes its style to German Expressionism, and to the influx of European directors to the U.S. during World War II.

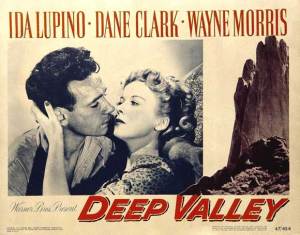

Every student of film noir knows that the genre owes its style to German Expressionism, and to the influx of European directors to the U.S. during World War II. One day, she discovers a crew of prisoners working on a chain gang along the ocean, excavating and dynamiting the coastline in preparation for a highway. This destruction and remaking of the natural world will bring a steady flow of people past the Sauls’ farm, and radically change Libby’s life.

One day, she discovers a crew of prisoners working on a chain gang along the ocean, excavating and dynamiting the coastline in preparation for a highway. This destruction and remaking of the natural world will bring a steady flow of people past the Sauls’ farm, and radically change Libby’s life.