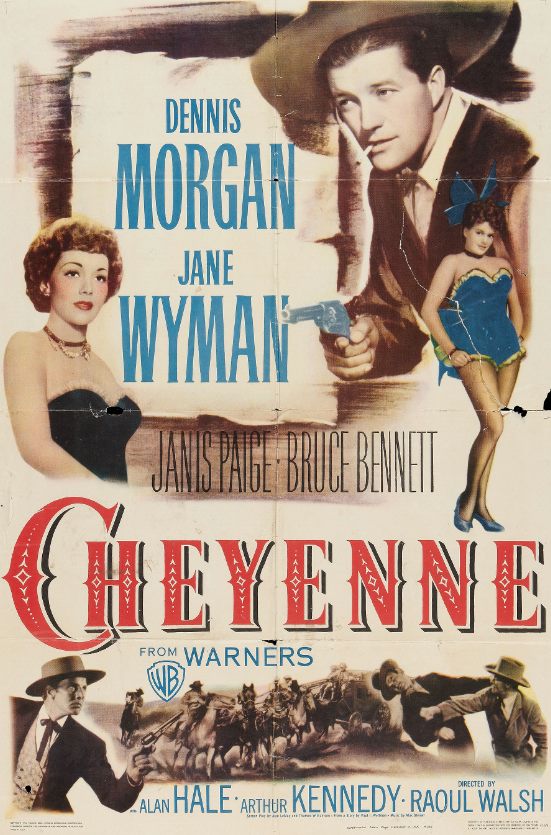

Cheyenne (1947)

Directed by Raoul Walsh

Warner Bros.

Most of the time, when people say “adult western,” they’re talking about the more psychologically realistic western dramas that stood apart from the fray of Saturday matinee singing cowboys. They’re talking about the films of John Ford and Anthony Mann, and TV series like Gunsmoke (1955-1975). Raoul Walsh’s Cheyenne is a different kind of adult western.

While tame by the standards of today’s R-rated movies and cable TV, Cheyenne is a feast of double entendres and sexually suggestive scenes and dialogue. The film stars Dennis Morgan — doing his best impression of George Sanders — as James Wylie, a gentleman gambler who’s impressed into the service of the law by private detective Webb Yancey (Barton MacLane).

Yancey offers to cut Wylie in on the $20,000 reward being offered for “The Poet,” who’s responsible for a series of stagecoach robberies along the Wells Fargo line. Wherever the Poet strikes, he leaves a piece of paper with a few lines of verse, such as “I’m happy the frontier is settling down / With a thriving bank in every town / Let the riders and nesters deposit their pay / So I and my gun can take it away.”

Cheyenne co-stars Jane Wyman (back when she was still Mrs. Ronald Reagan) as a woman named Ann Kincaid. Ann is married to a Wells Fargo banker named Ed Landers (Bruce Bennett), but their marriage is on the rocks, and she’s clearly attracted to the dashing and roguish Wylie. Of course, for the sake of propriety (and the Hays Code), she acts as though she can’t stand Wylie.

There’s plenty of lighthearted, sexy banter, and great lines like, “How did I know she was the sheriff’s daughter? I couldn’t find a badge.” Or my personal favorite, “You know how women are. Like bears. They never get enough honey.”

Ann and Wylie’s situation is complicated when they fall in with a gang led by the Sundance Kid (Arthur Kennedy). Kennedy plays his role with brio. Sundance is a snarling badass who shoots first and thinks later. When a young punk in his gang stands up to him, and says that the Sundance Kid may have all the other members of his gang buffaloed but he doesn’t fool him, Sundance kicks him to the ground and shoots him dead.

Wylie tells Sundance that he is in fact the Poet, and offers to cut him in on the take from his robberies. He also claims that Ann is his wife, which leads to some sexy playacting. Maybe too sexy. As one of Sundance’s gang says, “He kissed the gal like he liked it. That ain’t like no husband.”

When they go to bed in the same room because some of Sundance’s gang are outside watching, Wylie says, “I’ll sleep with one eye open.” Ann responds, “What do you think I’m gonna do?”

The sexual suggestions aren’t limited to the dialogue. The old spinster housekeeper’s look of regret when Ann says “You know how men are” is priceless. And even I couldn’t believe the scene in which Ann complains about back pain after the night she spends with Wylie.

The sexiness doesn’t stop with Jane Wyman. Janis Paige gives a good performance as a voluptuous saloon singer named Emily Carson. The two songs she performs in a black bustier, dark stockings, and high heels — M.K. Jerome & Ted Koehler’s “I’m So in Love” and Max Steiner & Ted Koehler’s “Going Back to Old Cheyenne” — were a high point of the picture for me.

I enjoyed Cheyenne quite a bit, but it’s not as interesting as Raoul Walsh’s previous western, Pursued (1947), and it suffers from wild shifts in tone. Most of the film is sexy and playful, but the action scenes are surprisingly dark and violent.

Cheyenne is definitely worth seeing for fans of westerns and aficionados of its prolific and talented director. The actors are all fun to watch, especially Arthur Kennedy, and Max Steiner’s bombastic score does a nice job of propelling the action during the film’s shootouts and chase scenes.