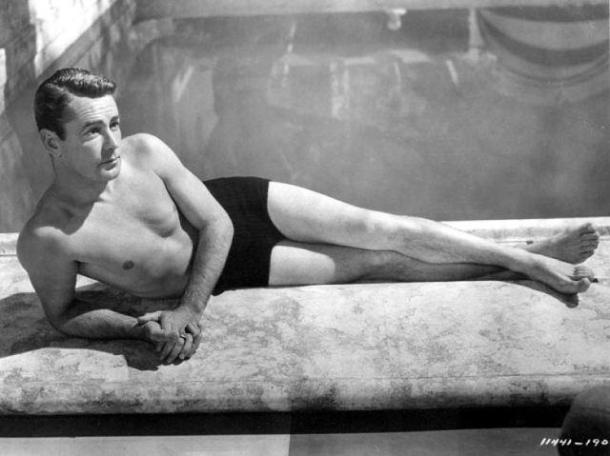

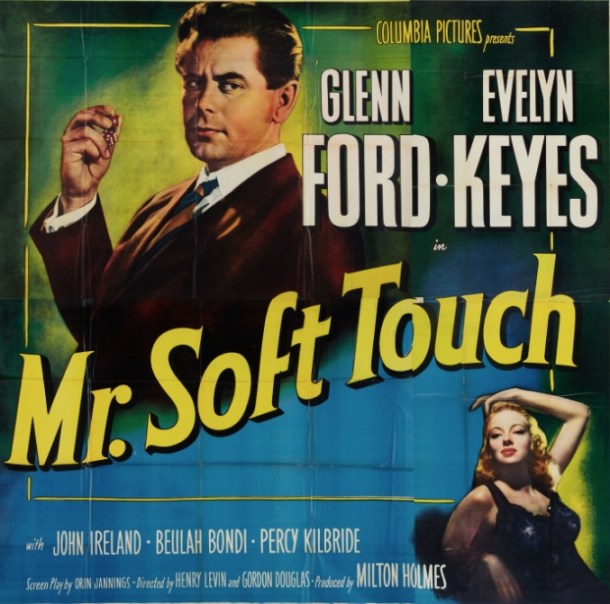

Mr. Soft Touch (1949)

Directed by Gordon Douglas and Henry Levin

Columbia Pictures

I saw Mr. Soft Touch two weeks ago at the Music Box Theatre, and I loved everything about it.

I couldn’t find many reviews of Mr. Soft Touch online, but most of the reviews I found were lukewarm, and criticized its dichotomous nature. “It can’t make up its mind if it wants to be a film noir or a comedy” seems to be the consensus. Another refrain I saw was “Could have been a holiday classic but misses the mark.”

Most of those reviews blame the fact that the film has two directors.

Well, for once in my life I don’t care what went on behind the scenes, or which director contributed to what parts of the film, because I loved Mr. Soft Touch and I’ll sing its praises from the rooftops.

It probably helped that I saw it on the big screen in a real theater on a gloomy winter afternoon. If it wasn’t a pristine and fully restored 35mm print then it was a damned good facsimile of one. I watch most of the movies I review on DVD (occasionally Blu-ray) or on a streaming service, but that’s out of necessity. If you love classic films there is simply no substitute for the theatrical experience.

Mr. Soft Touch stars Glenn Ford as Joe Miracle, a shady character who’s running from the law with a bag full of cash when the movie begins. The opening sequence is suspenseful and features some great San Francisco location shooting. Joe Miracle uses his wits to get through a series of close shaves and eventually winds up hiding out for several days in a settlement house run by a woman named Jenny Jones (Evelyn Keyes).

The settlement house is staffed by Jenny and a group of older women, including actresses Beulah Bondi and Clara Blandick. They tend to the needs of homeless men, juvenile delinquents, and poor immigrants.

For the first reel or two of Mr. Soft Touch I kept waiting for a flashback sequence that would show how Joe Miracle wound up with a bag full of cash, fleeing for his life, and biding his time until he can hop on a steamer bound for Japan. A flashback like that would have been a classic film noir device, but the story unfolds in a linear fashion, and everything is explained along the way.

A bunch of gangland toughs are on Joe’s tail, and they’re led by the always entertaining mug Ted de Corsia. There’s also a muckraking radio reporter, Henry “Early” Byrd (played by a bespectacled John Ireland), who sends warnings to Joe over the airwaves but who might not have Joe’s best interests at heart.

Significantly, Mr. Soft Touch takes place at Christmastime, and adds the layer of “holiday film” to the already rare blending of hard-boiled noir, romantic comedy, and “social issues” picture.

I got very involved with the story and characters in Mr. Soft Touch. I tend to dislike movies that have an inconsistent tone. Despite the blending of genres, I never felt like the tone of Mr. Soft Touch shifted uncomfortably from one genre to another. It was unpredictable, but it all worked.

I don’t know which director did what, but I never had the sense that there were two different films fighting each other for supremacy. Mr. Soft Touch is all about dualities, though, so perhaps having two directors works in the film’s favor. Joe Miracle’s last name is an Americanization of a much longer Polish surname that starts with the letter M. But it also symbolizes the unexpected gifts of the holiday season, and the element of the unexpected that he brings to Jenny’s settlement house. The title of the film has a double meaning, too. Joe Miracle has hands that can make the dice in a craps game come up the way he wants them, but the title of the film also refers to the goodness lurking behind his tough exterior that Jenny helps expose.

It’s a somewhat odd film, but a thoroughly enjoyable one.