Nothing spices up a love triangle like murder.

Nothing spices up a love triangle like murder.

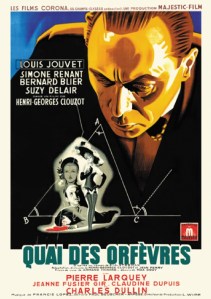

And nothing elevates a routine police procedural like the sure hand of director Henri-Georges Clouzot, who is ultimately less interested in the mechanics of unraveling a murder mystery than he is in showing human life in all of its sordid glory.

Quai des Orfèvres is based on Stanislas-André Steeman’s 1942 novel Légitime défense, which Clouzot adapted from memory when he was unable to locate a copy.

The plot isn’t hard to summarize. What is hard to convey is the richness of its characters and its evocation of the messiness of real life.

Quai des Orfèvres is a film in which a woman complains about a nail in her shoe poking her foot, in which a tense police interview takes place next to a pair of cops inspecting and discussing a fishing pole, in which a police inspector who comes round asking questions ends up shuffling around on carpet slippers because the floors have just been waxed, and in which a man opens his veins in a jail cell on Christmas Eve while the prostitute in the cell next to him natters on about inconsequential matters, not realizing what’s going on right next to her.

The film demonstrates a sense of the movement of time that few films do. It begins in early December and marches on inexorably toward Christmas. At first, Paris looks cold and damp, but toward the end of the picture we see fat flakes of snow beginning to fall slowly outside the windows of the police station.

The aforementioned plot involves a bald, chubby pianist-accompanist named Maurice Martineau (Bernard Blier) and his coquettish wife, a music-hall singer whose stage name is Jenny Lamour (Suzy Delair). The two couldn’t be less alike, and Maurice is constantly jealous of his wife. The two share a friendship with their neighbor, Dora Monier (Simone Renant), a photographer who is as perceptive and close-lipped as Maurice and Jenny are hot-tempered and argumentative.

Things come to a head when Jenny begins meeting with a dirty-old-man producer named Georges Brignon (Charles Dullin, a legend of the French stage, in his last film role). She wants a part in a movie. Maurice wants Brignon to stay far, far away from his wife.

On the night when Jenny is set to go to Brignon’s house for a romantic dinner, Maurice cooks up a half-baked scheme. He’ll go to the theater for a show and be seen by his friends in the business before and after the show, but during the show, he’ll quietly slip out with his revolver in his pocket and drive to Brignon’s house.

It’s never made clear whether he plans to kill both Brignon and his wife or just Brignon, and we never find out, because when he arrives at Brignon’s house, Brignon has already been killed.

And worse, when he flees the scene, he finds his car has been stolen, which means he barely gets back to the theater in time to shuffle out with the stragglers, which pokes a few holes in his alibi.

Meanwhile, Jenny admits to her friend Dora that she hit Brignon over the head with a bottle when he became too amorous, and Dora goes to Brignon’s house to clean up the scene.

Enter Inspector Antoine of the Paris police (Louis Jouvet).

Enter Inspector Antoine of the Paris police (Louis Jouvet).

Inspector Antoine is no Sherlock Holmes. He’s a detective for a homicide department that currently has a 48% clearance rate. But he is a dogged investigator, and as any Columbo fan knows, beware a hangdog police detective with a runny nose who never, ever gives up.

The character of Antoine — perfectly played by Jouvet — is a great example of how Clouzot injects little unexpected moments to make characters three-dimensional. For instance, Antoine is a single father raising a mixed-race son. When he learns that his son has failed one of his final exams — that pesky geometry — Antoine is upset, and mutters that he’ll just have to give his son the Meccano set he already bought him as a Christmas present instead.

Oh, and remember that love triangle I referred to in the lede? At first it seems that Dora has feelings for Maurice, but it very quickly becomes clear that her feelings are for Jenny. The fact that she is a lesbian is handled delicately, but is confirmed late in the film when Antoine tells her, “When it comes to women, we’ll never have a chance.”

Quai des Orfèvres is a remarkable film. It doesn’t have the heart-stopping suspense of some of Clouzot’s more famous later pictures, like Le salaire de la peur (The Wages of Fear) (1953) and Diabolique (1955), but it’s an extraordinarily well-made, well-acted, richly textured, and involving movie that I couldn’t wait to see again as soon as it was over.