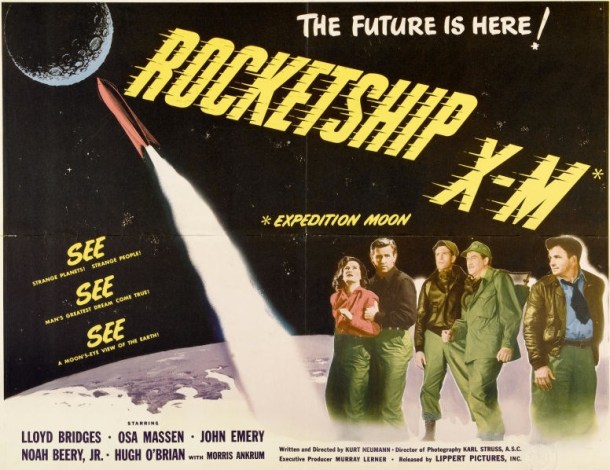

Rocketship X-M (1950)

Directed by Kurt Neumann

Lippert Pictures

The classic era of Hollywood science fiction begins here.

There were science fiction from the very birth of the medium. One of the earliest narrative films ever made was Georges Méliès’s A Trip to the Moon (1902), and the silent era saw science-fiction masterworks like Fritz Lang’s Metropolis (1927).

In the 1930s, sci-fi ranged from the Saturday-matinee action of Flash Gordon to the serious-minded speculations of Things to Come (1936).

During World War II, sci-fi all but disappeared from movie screens. (Although it always flourished in the pulp magazines no matter what Hollywood was doing.) But the 1950s were an incredible time for cinematic sci-fi, and that era started with Rocketship X-M and Destination Moon (1950).

Kurt Neumann’s Rocketship X-M came out just a month earlier than producer George Pal’s Destination Moon, which was a lavish and much anticipated Technicolor extravaganza. Rocketship X-M, on the other hand, was shot in less than three weeks with a budget of less than $100,000, which was how it was able to beat Pal’s production into theaters. (Apparently the similarity of the two films led Lippert Pictures to include the disclaimer “This is not ‘Destination Moon'” in the promotional material they sent to distributors.)

Just like Destination Moon, this film takes many elements from Robert A. Heinlein’s “boys’ adventure” novel Rocket Ship Galileo, which was published in 1947. Unlike Destination Moon, it’s not an official adaptation, which might account for the decision to have unforeseen circumstances lead to the crew of the Rocketship X-M (which stands for “expedition moon”) badly overshooting the mark and winding up on Mars.

The equipment seen in the film was provided by the Allied Aircraft Company of North Hollywood, so it doesn’t look particularly cheap or overly “fake,” but you’ll run out of fingers if you start counting all the inaccuracies in Rocketship X-M — the crew give a press conference with less than 15 minutes to go until launch, meteoroids fly in a tight cluster and smash into the ship at one point, there is sound in space, and so on.

Some of the scientific inaccuracies can be chalked up to the low budget. The film acknowledges that weightlessness is a part of space travel, but only partway. Small objects float up into the air and enormous fuel tanks are easy for the crew members to lift and maneuver, but their bodies all stay firmly in place.

Despite the budgetary limitations and scientific inaccuracies, I thought Rocketship X-M was a phenomenal sci-fi movie. All the things that money can’t buy — good performances, exciting story, crisp dialogue, imaginative use of earthbound locations to suggest other planets — are up there on screen.

The script for Rocketship X-M was mostly written by the great Dalton Trumbo. Because he was blacklisted, Trumbo’s name doesn’t appear in the credits. The sharply drawn characters, the believable dialogue, and the progressive politics are all Trumbo trademarks. Several of the male characters in the film say and do sexist things, but the script itself is not sexist. For instance, after the crew has had their medical examinations, Col. Floyd Graham (Lloyd Bridges) points to Dr. Lisa Van Horn (Osa Massen) and wryly says, “The ‘weaker sex.’ The only one whose blood pressure is normal.” Later in the film, a male scientist confidently tells her to recheck her calculations because they don’t jibe with his and she apologizes — but it turns out later that hers are correct, and his insistence that he is right has dire consequences for the mission.

Most significantly, the film imagines a Mars devastated by a long-ago nuclear war. The possibly cataclysmic consequences of atomic war is a science-fiction concept that can be found in E.C. Comics (specifically Weird Fantasy #13) published around the same time that Rocketship X-M was released, and even earlier in a radio show written by Arch Oboler, but it was a new concept for a Hollywood film.

The 1950s would see plenty of politically reactionary sci-fi movies in which square-jawed American he-men faced alien menaces and came out on top, but there were a fair number of ’50s sci-fi movies that took a dimmer view of America’s growing nuclear arsenal and burgeoning militarism, like The Day the Earth Stood Still (1951). Rocketship X-M was the first of these type of sci-fi movies, and it still stands up as superior entertainment.

Republic Pictures is the unassailable king of the cliffhangers after the silent era. Most of the best chapterplays of the ’30s and ’40s were Republic productions. Dick Tracy (1937), The Lone Ranger (1938), Zorro’s Fighting Legion (1939), Adventures of Red Ryder (1940), Mysterious Doctor Satan (1940), Adventures of Captain Marvel (1941), Jungle Girl (1941), Spy Smasher (1942), Perils of Nyoka (1942), The Masked Marvel (1943), and Captain America (1944) are just a few of the more than sixty serials produced by Republic Pictures, most of which are still incredibly entertaining. The best Republic serials combined wild action and elaborate stunts with nicely paced stories that could be strung out over 12 to 15 weekly installments with a few subplots here and there, but nothing too complicated or that viewers couldn’t pick up with in the middle. Each chapter ended with a cliffhanger (like Captain Marvel flying toward a woman falling off a dam, or a wall of fire rushing down a tunnel toward Spy Smasher). The next week’s chapter would begin with a minute or two of the previous week’s climax and the resolution, and the cycle would repeat until the final chapter.

Republic Pictures is the unassailable king of the cliffhangers after the silent era. Most of the best chapterplays of the ’30s and ’40s were Republic productions. Dick Tracy (1937), The Lone Ranger (1938), Zorro’s Fighting Legion (1939), Adventures of Red Ryder (1940), Mysterious Doctor Satan (1940), Adventures of Captain Marvel (1941), Jungle Girl (1941), Spy Smasher (1942), Perils of Nyoka (1942), The Masked Marvel (1943), and Captain America (1944) are just a few of the more than sixty serials produced by Republic Pictures, most of which are still incredibly entertaining. The best Republic serials combined wild action and elaborate stunts with nicely paced stories that could be strung out over 12 to 15 weekly installments with a few subplots here and there, but nothing too complicated or that viewers couldn’t pick up with in the middle. Each chapter ended with a cliffhanger (like Captain Marvel flying toward a woman falling off a dam, or a wall of fire rushing down a tunnel toward Spy Smasher). The next week’s chapter would begin with a minute or two of the previous week’s climax and the resolution, and the cycle would repeat until the final chapter. The first film serial featuring Secret Agent X-9 was made by Universal in 1937, and starred Scott Kolk as Agent X-9, a.k.a. “Dexter,” who sought to recover the crown jewels of Belgravia from a master thief called “Blackstone.” The second featured a boyish-looking 32-year-old Lloyd Bridges as Agent X-9, a.k.a. “Phil Corrigan.” Made toward the end of World War II, the 1945 iteration of the character focused on wartime intrigue and Corrigan’s cat-and-mouse games with Axis spies. Taking a cue from Casablanca (1942), the serial was set in a neutral country called “Shadow Island,” in which Americans, Japanese, Chinese, French, Germans, Australians, and the seafaring riffraff of the world freely intermingle. A fictional island nation off the coast of China, “Shadow Island” has a de facto leader named “Lucky Kamber” (Cy Kendall) who owns a bar called “House of Shadows” and has a finger in every pie, including gambling and espionage. Various German and Japanese military officers, secret agents, and thugs run amuck in this serial, but the one who most stands out is the unfortunately made-up and attired Victoria Horne as “Nabura.” In her role as a Japanese spymaster, Horne is outfitted with eyepieces that cover her upper eyelids, appearing to drag them down from sheer weight. She doesn’t look Asian, she just looks as if her eyes are closed.

The first film serial featuring Secret Agent X-9 was made by Universal in 1937, and starred Scott Kolk as Agent X-9, a.k.a. “Dexter,” who sought to recover the crown jewels of Belgravia from a master thief called “Blackstone.” The second featured a boyish-looking 32-year-old Lloyd Bridges as Agent X-9, a.k.a. “Phil Corrigan.” Made toward the end of World War II, the 1945 iteration of the character focused on wartime intrigue and Corrigan’s cat-and-mouse games with Axis spies. Taking a cue from Casablanca (1942), the serial was set in a neutral country called “Shadow Island,” in which Americans, Japanese, Chinese, French, Germans, Australians, and the seafaring riffraff of the world freely intermingle. A fictional island nation off the coast of China, “Shadow Island” has a de facto leader named “Lucky Kamber” (Cy Kendall) who owns a bar called “House of Shadows” and has a finger in every pie, including gambling and espionage. Various German and Japanese military officers, secret agents, and thugs run amuck in this serial, but the one who most stands out is the unfortunately made-up and attired Victoria Horne as “Nabura.” In her role as a Japanese spymaster, Horne is outfitted with eyepieces that cover her upper eyelids, appearing to drag them down from sheer weight. She doesn’t look Asian, she just looks as if her eyes are closed. Apparently populist rage against pharmaceutical giants is nothing new. In Strange Confession, the fifth of six “Inner Sanctum Mysteries” produced by Universal Pictures and released from 1943 to 1945, Lon Chaney, Jr. plays a brilliant chemist named Jeff Carter whose life goes from bad to worse when he twice accepts employment from the unscrupulous owner of the largest medical distributing company in an unnamed American city.

Apparently populist rage against pharmaceutical giants is nothing new. In Strange Confession, the fifth of six “Inner Sanctum Mysteries” produced by Universal Pictures and released from 1943 to 1945, Lon Chaney, Jr. plays a brilliant chemist named Jeff Carter whose life goes from bad to worse when he twice accepts employment from the unscrupulous owner of the largest medical distributing company in an unnamed American city.