Complaining that William A. Wellman’s Magic Town is built on a faulty premise is kind of like complaining that Cadbury Creme Eggs are too sweet, but I’m going to do it anyway.

Complaining that William A. Wellman’s Magic Town is built on a faulty premise is kind of like complaining that Cadbury Creme Eggs are too sweet, but I’m going to do it anyway.

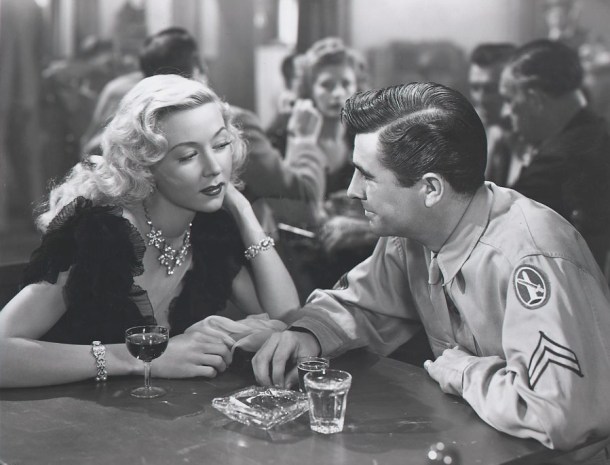

Magic Town, which is written by frequent Frank Capra collaborator Robert Riskin, is about a public opinion pollster named Lawrence “Rip” Smith (James Stewart) whose small polling company has just gone out of business because of high overhead costs. To stay afloat, Rip starts looking for a mathematical miracle in order to conduct public opinion polls without nationwide coverage.

He finds the shortcut he’s been looking for in a little town called Grandview.

You see, Grandview has the exact same distribution of Republicans and Democrats, men and women, old and young, farmers and laborers, and so on, as the nation as a whole. In other words, Grandview thinks exactly the same way the entire United States does. Instead of exhaustive telephone polling of representative swaths of the nation, all Rip will need to do is find out what people in Grandview think, and he’ll be able to extrapolate the results.

The catch is that the people of Grandview can’t know what Rip is up to, otherwise they’ll become self-conscious, and it’ll kill the goose that lays golden eggs. So Rip and his partners, Ike (Ned Sparks) and Mr. Twiddle (Donald Meek), head for Grandview, where they pass themselves off as insurance men from Hartford, Connecticut. They’ll engage in stealth polling, pretending to offer insurance policies while they’re really making note of the current issues the citizens of Grandview are all too willing to sound off about.

Rip’s plan hits a snag as soon as he hits town, where he reconnects with an old friend from his days in the service — Mr. Hoopendecker (Kent Smith) — who is now principal of Grandview High School. The snag is pretty local girl Mary Peterman (Jane Wyman), who’s a civic crusader, and is constantly pushing to modernize the town and build a new civic center.

Rip’s “perfect” town and its “perfect” demographics can’t be altered in any way for his covert polling operation to work, so he opposes Mary’s plans. He tells the city council that Grandview is “A sturdy challenge to the evils of the modern era.” He encourages them not to modernize anything and not to change anything.

And herein lies the problem, and the reason I said that Magic Town is built on a faulty premise. Grandview supposedly perfectly mirrors the demographics of the United States as a whole, but it’s consistently represented as an idyllic Utopia, unchanging, and a refuge from the outside world. (It’s also oddly free of blacks and Jews.)

So Magic Town is less about a town that represents America in miniature than it is about one of the most enduring American myths — the sanctity and perfection of small-town life. Grandview doesn’t represent what America actually is, it’s what America wishes it was.

Rip finds happiness in Grandview. He and Mary fall in love. He and Hoopendecker relive old times. Rip coaches the boys’ basketball team and turns them into winners.

All this could have been funny, romantic, and charming, but the film persists with its idiotic plot about opinion polling. Eventually Mary finds out what Rip is really up to and “outs” him in the press. There follows a nationwide rush to move to this “mathematically perfect” town. The civic center is approved and the citizens of Grandview become full of themselves and start forming and selling their own opinions.

And just as Rip predicted, their self-consciousness destroys everything, and results in the following newspaper headline: “GRANDVIEW COMPLETES FIRST POLL. 79% Favor Woman for President. ‘RESULT RIDICULOUS!’ SAYS EXPERT.”

All the newcomers move out of the now not-so-magic town, but things don’t go back to normal. Grandview is in shambles, and it’s up to Rip to fix things.

Despite the weak story, I enjoyed all of the actors in Magic Town, especially Stewart. He’s been parodied and impersonated so many times that it’s easy to forget what a good actor he was. He didn’t always play good guys, but when he did, no one projected the same kind of sweetness, generosity, and earnestness.

Magic Town is sort of a “greatest hits” compilation of earlier, better films that Stewart starred in. There’s the same celebration of small-town life found in It’s a Wonderful Life (1946) and there’s even a scene in which Stewart gives an impassioned speech while being supported by a bunch of kids, just like in Mr. Smith Goes to Washington (1939). It’s nowhere near as good as either of those films, but it’s not without its modest pleasures, as long as you don’t think about it too hard.