Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger, the talented pair of writers, producers, and directors whose early collaborations included One of Our Aircraft Is Missing (1942), The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp (1943), and A Canterbury Tale (1944), worked together under the name “The Archers” throughout the 1940s and 1950s, and produced some of the most enduring films in British history. Powell was a native-born Englishman. Pressburger was a Hungarian Jew who found refuge in London and who prided himself on being “more English than the English.”

Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger, the talented pair of writers, producers, and directors whose early collaborations included One of Our Aircraft Is Missing (1942), The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp (1943), and A Canterbury Tale (1944), worked together under the name “The Archers” throughout the 1940s and 1950s, and produced some of the most enduring films in British history. Powell was a native-born Englishman. Pressburger was a Hungarian Jew who found refuge in London and who prided himself on being “more English than the English.”

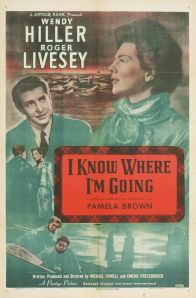

I Know Where I’m Going, which premiered in London on November 16, 1945, is a warm, romantic drama. The film stars Wendy Hiller as Joan Webster, a stubborn young woman who, according the narrator, “always knew where she was going.” After a montage that shows Joan’s growth from headstrong toddler to headstrong teenager to headstrong 25-year-old, we see her dressed in smart clothes, meeting her father (played by George Carney) at a nightclub, where she blithely informs him that she plans to travel to Kiloran island in Scotland to marry Sir Robert Bellinger, a wealthy, middle-aged industrialist whom she has never met. Her father is aghast, but, as always, Joan knows exactly where she’s going and what she’s doing.

Handled differently, this setup could lead to a grim, Victorian melodrama, but I Know Where I’m Going is a playful film with touches of magical realism. On her trek to the Hebrides, Powell and Pressburger delight in each leg of her long journey (and there are many), and pepper the montage with fanciful touches, such as a map with hills made of tartan plaid, a dream sequence in which Joan’s father marries her to the chemical company owned by Bellinger (literally), and an old man’s top hat that becomes the whistling chimney of a steam engine.

On the last leg of her journey, she is forced to put up in the Isle of Mull, as weather conditions do not permit water travel to Kiloran. Joan stays in touch with Bellinger, who is never seen, only heard (as a stuffy voice on the other end of a telephone). While cooling her heels in Mull, Joan meets a charming, soft-spoken serviceman named Torquil MacNeil, who is on an eight-day leave. (Torquil is played by Roger Livesey, in a role originally intended for James Mason.)

The joke implicit in the title becomes more and more clear as Joan and Torquil begin to fall for each other. The closer they become, the more determined she is to reach Kiloran. Eventually willing to risk life and limb to get there, it becomes clear that at least when it comes to love, she has no idea where she is going, and is too hard-headed to see anything clearly.

Livesey, who was in his late thirties when this film was made, was originally told that he was too old and too heavy to play the role of the 33-year-old Torquil, but he very quickly slimmed down to get the part, and he cuts a dashing figure, although not a classically handsome one. Interestingly, Livesey never set foot in the Western Isles of Scotland, where most of the film’s exteriors were shot. He was starring in a play in the West End during filming, so Powell and Pressburger made clever use of a body double for long shots, and filmed all of Livesey’s interior scenes at Denham Studios, in England.

Besides its fine performances and its involving love story, I Know Where I’m Going is enjoyable to watch simply because Powell and Pressburger show such incredible attention to detail. The interiors may be shot on a soundstage, but it’s easy to forget that with effects that perfectly marry them to the location footage, such as rain lashing the windows, subtle lighting, and the shadows of tree branches moving back and forth on the walls of the houses and cottages on the island. There are no short cuts or cut corners in this film. Joan’s dreams don’t appear in a cloud of dry ice or in soft focus, they swirl kaleidoscopically around her head. And elements that might seem silly in another film, such as an ancient curse hanging over Torquil’s head, seem palpably real when they’re embodied by shadowy, decrepit, and glorious real-world locations like Moy Castle.

French film director Robert Bresson is famous for his use of non-professional actors. Prior to watching Les Dames du Bois de Boulogne, I had only seen one Bresson film, Pickpocket (1959), whose protagonist was most certainly not a professional actor. He shambled through the proceedings like a man on a heavy dose of tranquilizers, his movements slow, his eyes haunted. It was an interesting film, and one I may watch again some day, but it didn’t move me.

French film director Robert Bresson is famous for his use of non-professional actors. Prior to watching Les Dames du Bois de Boulogne, I had only seen one Bresson film, Pickpocket (1959), whose protagonist was most certainly not a professional actor. He shambled through the proceedings like a man on a heavy dose of tranquilizers, his movements slow, his eyes haunted. It was an interesting film, and one I may watch again some day, but it didn’t move me. Barbara Stanwyck was a superstar of screwball comedies, and she created one of the all-time great femmes fatales in Billy Wilder’s Double Indemnity (1944). Christmas in Connecticut is one of her minor efforts, but it’s amusing enough, and if you’re specifically looking for a holiday film, you could do a lot worse.

Barbara Stanwyck was a superstar of screwball comedies, and she created one of the all-time great femmes fatales in Billy Wilder’s Double Indemnity (1944). Christmas in Connecticut is one of her minor efforts, but it’s amusing enough, and if you’re specifically looking for a holiday film, you could do a lot worse. I don’t generally like musicals, but I loved Anchors Aweigh. It probably doesn’t hurt that I really like both Frank Sinatra and Gene Kelly, and this movie uses both of them to wonderful effect. Kelly’s dance sequences are all high points, and even Sinatra comports himself well in the one dance in which he has to match Kelly step-for-step. Although I can only imagine how many takes it took to get it right. Unlike today’s hyperkinetic editing styles, most of the dance sequences in Anchors Aweigh are done in what appear to be one take, or just a few at most.

I don’t generally like musicals, but I loved Anchors Aweigh. It probably doesn’t hurt that I really like both Frank Sinatra and Gene Kelly, and this movie uses both of them to wonderful effect. Kelly’s dance sequences are all high points, and even Sinatra comports himself well in the one dance in which he has to match Kelly step-for-step. Although I can only imagine how many takes it took to get it right. Unlike today’s hyperkinetic editing styles, most of the dance sequences in Anchors Aweigh are done in what appear to be one take, or just a few at most. The Clock is the first film Judy Garland made in which she did not sing. She had specifically requested to star in a dramatic role, since the strenuous shooting schedules of lavish musicals were beginning to fray her nerves. Producer Arthur Freed approached her with the script for The Clock (also known as Under the Clock), which was based on an unpublished short story by Paul and Pauline Gallico. Originally Fred Zinnemann was set to direct, but Garland felt they had no chemistry, and she was disappointed by early footage. Zinnemann was removed from the project, and she requested that Vincente Minnelli be brought in to direct.

The Clock is the first film Judy Garland made in which she did not sing. She had specifically requested to star in a dramatic role, since the strenuous shooting schedules of lavish musicals were beginning to fray her nerves. Producer Arthur Freed approached her with the script for The Clock (also known as Under the Clock), which was based on an unpublished short story by Paul and Pauline Gallico. Originally Fred Zinnemann was set to direct, but Garland felt they had no chemistry, and she was disappointed by early footage. Zinnemann was removed from the project, and she requested that Vincente Minnelli be brought in to direct.