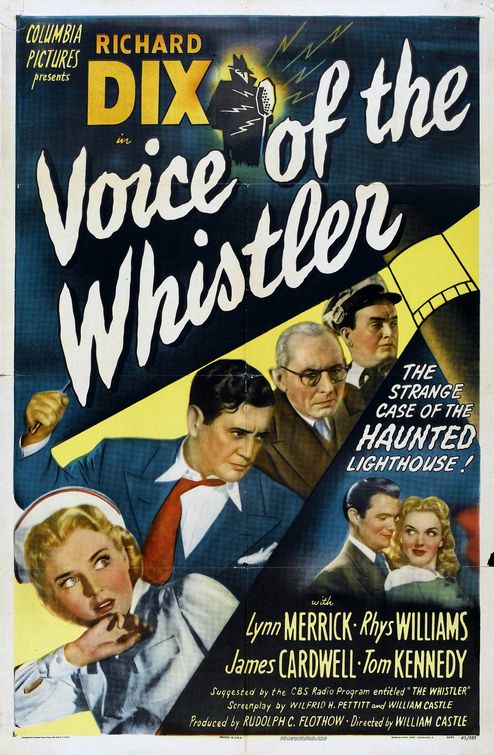

Voice of the Whistler (1945)

Directed by William Castle

Columbia Pictures

The Whistler, which was first heard on the Columbia Broadcasting System on May 16, 1942, ran for more than 13 years and was one of the best mystery and suspense programs on the radio. It didn’t feature the well-known Hollywood stars of Suspense (also broadcast on CBS), but its scripts were some of the most clever and intriguing that old-time radio had to offer, and its final twists were always satisfying, whether or not you saw them coming.

The program was hosted by a mysterious character embodied only by the sounds of footsteps and an eerie, whistled theme song. Each program began the same way, with the narrator saying, “I am the Whistler and I know many things, for I walk by night. I know many strange tales hidden in the hearts of men and women who have stepped into the shadows. Yes, I know the nameless terrors of which they dare not speak.” There were no recurring characters, but the situations were fairly similar from week to week. Greedy or vengeful people driven by dark impulses endeavored to commit perfect crimes, but were undone by a single overlooked detail or their own overreaching. Quite often, each story would contain more twists than just the one at the end. For instance, one program from October 1945 told the story of a man who killed his underworld partner and got away with it. He always wanted to reveal to the police the details of his clever scheme, but of course could not do so and remain a free man. After inadvertently faking his own death when a drifter steals his car and identification, crashes, dies, and is believed to be him, he changes his name and moves out of town. He then writes a mocking letter to the authorities laying out all the details of how he got away with murder. Immediately after mailing it, he hears on the radio that the police have determined that the body in the car wasn’t him after all, so he goes on a furious chase through the state in an attempt to retrieve the letter. He eventually attracts the attention of the police for tampering with the mail and is caught and confesses, only to find out at the end of the program that his letter was returned to his boarding house because it had incorrect postage.

Like Inner Sanctum Mysteries (another popular CBS suspense program), The Whistler was adapted as a series of B movies after it had been on the air for a couple of years. Starting with The Whistler (1944), which was directed by William Castle, the series continued with The Mark of the Whistler (1944), also directed by Castle, and The Power of the Whistler (1945), which was directed by Lew Landers. Each film starred Richard Dix, although he played a different role in each. The films did a great job of capturing the essence of the radio show. The Whistler was seen only in the shadows, just a man in a coat and a hat haunting alleyways and the dark parts of the city at night. Like the radio show, the Whistler’s voiceover often addressed the characters in the story, speaking in the second person, although he never interacted with them directly. (A typical bit might go, “You’ve really done it now, haven’t you? If you leave, they’ll see you, but if stay here, you’ll perish along with your victim. What are you going to do, George? What are you going to do?”)

Voice of the Whistler, which was directed by William Castle and written by Wilfred H. Petitt and Castle, working from a story by Allan Radar, tells the sad story of a successful industrialist named John Sinclair (Dix), whose fabulous wealth failed to provide him with either friends or health. After a breakdown, Sinclair changes his name to “John Carter” and goes away to lose himself. He sees a doctor who advises him to go to the sea coast, get some fresh air, a job, and enjoy himself. “And above everything, try to make friends,” the doctor tells him. “And never forget, Mr. Carter, that loneliness is a disease that can destroy a man’s mind.”

Sinclair moves to the coast of Maine and takes up residence in a lighthouse that has been converted into a private dwelling. Believing he doesn’t have long to live, he convinces a beautiful young nurse named Joan Martin (Lynn Merrick) to marry him. In exchange for her companionship during his last months, she will inherit all of his wealth. Although Joan is in love with a handsome young intern named Fred Graham (James Cardwell), they have been engaged for four years, and have no plans to be married until Fred can make enough money. Against Fred’s protests, Joan marries John, partly because she likes him and pities him, but mostly because his money can give her and Fred the life they’ve always wanted. After John and Joan have been married and living in the lighthouse with their jovial friend Ernie Sparrow (Rhys Williams) for several months, John’s health dramatically improves, and it looks as if Joan might have trouble collecting on their bargain. Meanwhile, John falls more and more in love with her. Eventually Fred shows up for a friendly visit that will have murderous consequences.

Richard Dix, a Hollywood star since the silent era, is great in each Whistler film I’ve seen him in so far. His glory days were behind him, but he was still a fine actor, and was equally adept at playing sympathetic protagonists and villains.

Pursuit to Algiers, the twelfth film to star Basil Rathbone as Sherlock Holmes and Nigel Bruce as his boon companion Dr. John H. Watson, is a minor entry in the series, but a thoroughly enjoyable one. It’s the ninth Holmes picture directed by Roy William Neill, and his sure hand and professionalism are fully in evidence.

Pursuit to Algiers, the twelfth film to star Basil Rathbone as Sherlock Holmes and Nigel Bruce as his boon companion Dr. John H. Watson, is a minor entry in the series, but a thoroughly enjoyable one. It’s the ninth Holmes picture directed by Roy William Neill, and his sure hand and professionalism are fully in evidence.

If you’ve only seen the film adaptation of James M. Cain’s 1941 novel Mildred Pierce, you’re forgiven for never wondering whether the striking murder set piece that opens the film and informs the entire picture was an invention of the producer and the screenwriters that never occurred in the novel.

If you’ve only seen the film adaptation of James M. Cain’s 1941 novel Mildred Pierce, you’re forgiven for never wondering whether the striking murder set piece that opens the film and informs the entire picture was an invention of the producer and the screenwriters that never occurred in the novel. Republic Pictures is the unassailable king of the cliffhangers after the silent era. Most of the best chapterplays of the ’30s and ’40s were Republic productions. Dick Tracy (1937), The Lone Ranger (1938), Zorro’s Fighting Legion (1939), Adventures of Red Ryder (1940), Mysterious Doctor Satan (1940), Adventures of Captain Marvel (1941), Jungle Girl (1941), Spy Smasher (1942), Perils of Nyoka (1942), The Masked Marvel (1943), and Captain America (1944) are just a few of the more than sixty serials produced by Republic Pictures, most of which are still incredibly entertaining. The best Republic serials combined wild action and elaborate stunts with nicely paced stories that could be strung out over 12 to 15 weekly installments with a few subplots here and there, but nothing too complicated or that viewers couldn’t pick up with in the middle. Each chapter ended with a cliffhanger (like Captain Marvel flying toward a woman falling off a dam, or a wall of fire rushing down a tunnel toward Spy Smasher). The next week’s chapter would begin with a minute or two of the previous week’s climax and the resolution, and the cycle would repeat until the final chapter.

Republic Pictures is the unassailable king of the cliffhangers after the silent era. Most of the best chapterplays of the ’30s and ’40s were Republic productions. Dick Tracy (1937), The Lone Ranger (1938), Zorro’s Fighting Legion (1939), Adventures of Red Ryder (1940), Mysterious Doctor Satan (1940), Adventures of Captain Marvel (1941), Jungle Girl (1941), Spy Smasher (1942), Perils of Nyoka (1942), The Masked Marvel (1943), and Captain America (1944) are just a few of the more than sixty serials produced by Republic Pictures, most of which are still incredibly entertaining. The best Republic serials combined wild action and elaborate stunts with nicely paced stories that could be strung out over 12 to 15 weekly installments with a few subplots here and there, but nothing too complicated or that viewers couldn’t pick up with in the middle. Each chapter ended with a cliffhanger (like Captain Marvel flying toward a woman falling off a dam, or a wall of fire rushing down a tunnel toward Spy Smasher). The next week’s chapter would begin with a minute or two of the previous week’s climax and the resolution, and the cycle would repeat until the final chapter. The first film serial featuring Secret Agent X-9 was made by Universal in 1937, and starred Scott Kolk as Agent X-9, a.k.a. “Dexter,” who sought to recover the crown jewels of Belgravia from a master thief called “Blackstone.” The second featured a boyish-looking 32-year-old Lloyd Bridges as Agent X-9, a.k.a. “Phil Corrigan.” Made toward the end of World War II, the 1945 iteration of the character focused on wartime intrigue and Corrigan’s cat-and-mouse games with Axis spies. Taking a cue from Casablanca (1942), the serial was set in a neutral country called “Shadow Island,” in which Americans, Japanese, Chinese, French, Germans, Australians, and the seafaring riffraff of the world freely intermingle. A fictional island nation off the coast of China, “Shadow Island” has a de facto leader named “Lucky Kamber” (Cy Kendall) who owns a bar called “House of Shadows” and has a finger in every pie, including gambling and espionage. Various German and Japanese military officers, secret agents, and thugs run amuck in this serial, but the one who most stands out is the unfortunately made-up and attired Victoria Horne as “Nabura.” In her role as a Japanese spymaster, Horne is outfitted with eyepieces that cover her upper eyelids, appearing to drag them down from sheer weight. She doesn’t look Asian, she just looks as if her eyes are closed.

The first film serial featuring Secret Agent X-9 was made by Universal in 1937, and starred Scott Kolk as Agent X-9, a.k.a. “Dexter,” who sought to recover the crown jewels of Belgravia from a master thief called “Blackstone.” The second featured a boyish-looking 32-year-old Lloyd Bridges as Agent X-9, a.k.a. “Phil Corrigan.” Made toward the end of World War II, the 1945 iteration of the character focused on wartime intrigue and Corrigan’s cat-and-mouse games with Axis spies. Taking a cue from Casablanca (1942), the serial was set in a neutral country called “Shadow Island,” in which Americans, Japanese, Chinese, French, Germans, Australians, and the seafaring riffraff of the world freely intermingle. A fictional island nation off the coast of China, “Shadow Island” has a de facto leader named “Lucky Kamber” (Cy Kendall) who owns a bar called “House of Shadows” and has a finger in every pie, including gambling and espionage. Various German and Japanese military officers, secret agents, and thugs run amuck in this serial, but the one who most stands out is the unfortunately made-up and attired Victoria Horne as “Nabura.” In her role as a Japanese spymaster, Horne is outfitted with eyepieces that cover her upper eyelids, appearing to drag them down from sheer weight. She doesn’t look Asian, she just looks as if her eyes are closed.

Abbott and Costello were one of the most popular comedy teams of the ’40s. They’re still famous for their “Who’s on first?” routine, and a lot of their film and radio work is still funny, as long as you’re in the mood for their old-fashioned brand of burlesque antics. If you’re not in the mood for them, or if one of their bits falls flat, Lou Costello is the most irritating man on earth.

Abbott and Costello were one of the most popular comedy teams of the ’40s. They’re still famous for their “Who’s on first?” routine, and a lot of their film and radio work is still funny, as long as you’re in the mood for their old-fashioned brand of burlesque antics. If you’re not in the mood for them, or if one of their bits falls flat, Lou Costello is the most irritating man on earth. Apparently populist rage against pharmaceutical giants is nothing new. In Strange Confession, the fifth of six “Inner Sanctum Mysteries” produced by Universal Pictures and released from 1943 to 1945, Lon Chaney, Jr. plays a brilliant chemist named Jeff Carter whose life goes from bad to worse when he twice accepts employment from the unscrupulous owner of the largest medical distributing company in an unnamed American city.

Apparently populist rage against pharmaceutical giants is nothing new. In Strange Confession, the fifth of six “Inner Sanctum Mysteries” produced by Universal Pictures and released from 1943 to 1945, Lon Chaney, Jr. plays a brilliant chemist named Jeff Carter whose life goes from bad to worse when he twice accepts employment from the unscrupulous owner of the largest medical distributing company in an unnamed American city.