Are there any fans of the old ABC TV series 77 Sunset Strip (1958-1964) out there?

Are there any fans of the old ABC TV series 77 Sunset Strip (1958-1964) out there?

If you have fond memories of that hepper than hep private eye show, you might be interested to know that this little mystery programmer is where it all started.

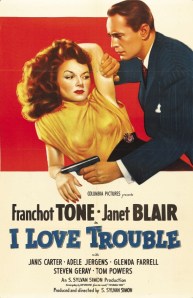

S. Sylvan Simon’s I Love Trouble is based on Roy Huggins’s novel The Double Take, and stars Franchot Tone as Stuart Bailey, a pencil-necked P.I. with a high forehead and an eye for the ladies.

Bailey was later (and more famously) played by Efrem Zimbalist Jr. — first in “Anything for Money,” an episode of the ABC series Conflict (1956-1957), and then in the ongoing series 77 Sunset Strip, where he was paired with a partner, Jeff Spencer (Roger Smith).

I haven’t read any novels by Roy Huggins, but if I Love Trouble is any indication, he was a writer firmly in the mold of Dashiell Hammett and Raymond Chandler. With a title like I Love Trouble, I was expecting a lighthearted mystery-comedy, so I was pleasantly surprised when it turned out to be a hard-boiled mystery with crisp dialogue and a well-rendered Los Angeles backdrop.

Ralph Johnston (Tom Powers), a wealthy gentleman who used to run with “a pretty rugged crowd,” hires Stuart Bailey to find out more about his wife Jane, who has been receiving threatening letters. Johnston says Jane is sheltered, unaccustomed to trouble, and couldn’t possibly be mixed up with anything shady. He believes one of his old friends resents Jane, got plastered, and sent her a threatening letter. Bailey responds that Jane spotted him tailing her, and that’s pretty uncommon for someone who was just a “nice quiet sorority girl at UCLA.”

Although he suspects there’s more to the story than Johnston is telling him, Bailey heads for Portland, Jane’s hometown, where he finds out that a high school diploma wasn’t the only piece of paper she picked up. She also got a work permit to dance at “Keller’s Carousel,” a seedy little club on South Broadway.

Keller (Steven Geray) and his henchman Reno (John Ireland) don’t take kindly to snoopers, and they send Bailey home with a few black-and-blue souvenirs.

Back in Los Angeles, Bailey is approached by a woman named Norma Shannon (Janet Blair), who claims to be Jane’s sister from Portland. But she doesn’t recognize the theatrical head shot of Jane sitting in Bailey’s apartment. What’s going on?

I Love Trouble is a solid B movie from Columbia Pictures. It’s chock-full of beautiful actresses (Adele Jergens doesn’t even rate a mention in my plot summary, but I sure was happy to see her in a swimsuit). It’s sometimes hard to distinguish one from another, but if you’re paying attention (and have ever read Chandler’s Lady in the Lake), you’ll realize why that actually works in the film’s favor.

As played by Tone, Stuart Bailey isn’t a very memorable character. Tone is simply too gangly and effete to be fully believable as a hard-boiled P.I, but the story is good, the dialogue is hard-boiled, and the action is tough and fast-paced. I especially enjoyed Bailey’s wisecracking secretary, Hazel “Bix” Bixby (Glenda Farrell).