Henry King’s Captain From Castile premiered on Christmas day in New York and Los Angeles, and went into wide release in January 1948.

Henry King’s Captain From Castile premiered on Christmas day in New York and Los Angeles, and went into wide release in January 1948.

It’s a lavish, Technicolor epic marred by a handful of flaws. The biggest flaw is that it doesn’t have an ending, and just sort of stops halfway through. The journey to the non-ending is uneven but generally entertaining and occasionally spectacular, which makes its abruptness all the more frustrating.

Captain From Castile is based on Samuel Shellabarger’s novel of the same name, which was published in early 1945. It was originally serialized, and was incredibly popular even before its publication in book form. Darryl F. Zanuck paid $100,000 for the rights, which was a lot of cabbage in the ’40s.

The film version only covers the first half of Shellabarger’s novel. Zanuck originally planned to exhibit Captain From Castile as a roadshow presentation with an intermission, so I’m not sure if the unsatisfying end was due to budget concerns or a flawed script. Three and a half months of shooting in Mexico wasn’t cheap, and the bottom kind of dropped out of movie-going in 1947 (after 1946, which was the biggest movie-going year of all time). Captain From Castile made its money back and then some, but it wasn’t a runaway success due to its incredibly high budget.

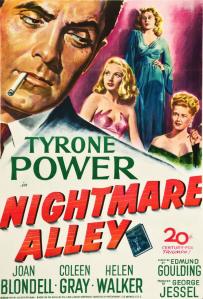

The film begins in Spain in the spring of 1518, and follows the progression of a young Castilian named Pedro de Vargas (played by Tyrone Power) from callow youth to victim of the Inquisition to seasoned soldier under the command of Hernando Cortés in Mexico. (Cortés is played to the laughing, mustache-twirling, swaggering hilt by Cesar Romero.)

The film begins in Spain in the spring of 1518, and follows the progression of a young Castilian named Pedro de Vargas (played by Tyrone Power) from callow youth to victim of the Inquisition to seasoned soldier under the command of Hernando Cortés in Mexico. (Cortés is played to the laughing, mustache-twirling, swaggering hilt by Cesar Romero.)

Despite the presence of swashbuckling superstar Tyrone Power, Captain From Castile isn’t really a swashbuckling adventure film. It’s a historical epic in which narrative tension is nonexistent for long stretches. All sequences involving the Cortés expedition were filmed in Mexico, and often on the location associated with the actual event. Captain From Castile always looks fantastic, but its story isn’t always up to the high standards of the visuals.

I really love Tyrone Power, though, and with all due respect to Errol Flynn, I think Power is the greatest swashbuckling star of all time. I also think he’s a much better actor than he’s given credit for, and he turns in a strong performance in Captain From Castile.

I really love Tyrone Power, though, and with all due respect to Errol Flynn, I think Power is the greatest swashbuckling star of all time. I also think he’s a much better actor than he’s given credit for, and he turns in a strong performance in Captain From Castile.

But moments of real power in the film are few and far between.

There’s one sequence, however, that I think stands as one of the best of Power’s career. After Pedro de Vargas is imprisoned by the Inquisition and his roguish friend Juan Garcia (Lee J. Cobb) has secreted weapons in his cell, his mortal enemy Diego de Silva (John Sutton) — the man responsible for Pedro’s sister’s death by torture — enters to taunt Pedro. This leads to a fast, brutal sword fight in close quarters that’s one of the best and most exciting I’ve ever seen.

Pedro’s romance with the servant girl Catana (played by the very inexperienced actress Jean Peters) is romantic and sexy — especially the scene in which Pedro dances with her in front of Cortés’s entire camp. The musical score by Alfred Newman is fantastic, and was one of the first film scores to be released as a soundtrack album.

The film looks amazing. The Technicolor cinematography is great, and the Mexican locations were so cooperative that the Paricutin volcano even agreed to erupt during filming to stand in for the eruption of Popocatepetl in the 16th century.

But there’s ultimately something a little slack and unsatisfying about Captain From Castile, and it’s not just the anticlimactic ending. I’d recommend Captain From Castile to all fans of bloated historical epics, but if you’ve never seen a Tyrone Power film, it’s not the best place to start.