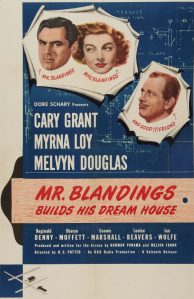

I don’t know about you, but comedies like H.C. Potter’s Mr. Blandings Builds His Dream House really stress me out.

I don’t know about you, but comedies like H.C. Potter’s Mr. Blandings Builds His Dream House really stress me out.

When the subject of “things I could never laugh at” comes up, most people think of things like the death of a beloved family pet or ethnic cleansing, but while I don’t find either of those subjects fertile ground for comedy, one subject stands above all others as something I can never laugh at — chasing good money after bad.

I don’t know if Mr. Blandings Builds His Dream House is the first comedy in which most of the “comedy” involves someone making terrible decision after terrible decision and throwing vast sums of money into a disastrous project, but it’s one of the best-known and most well-loved.

The first movie like this I saw was the 1986 Tom Hanks “comedy” The Money Pit, which even as a kid I found stressful and unfunny.

The second was the Joe McDoakes “comedy” short So You Want to Move (1950), in which every bad decision the main character makes and every accident he has is flashed on screen in dollar amounts. As the one-reeler continues, and he drops things and crashes into things, his financial responsibility grows and grows. As an argument for using professional movers, So You Want to Move is a persuasive infomercial, but as a comedy it’s totally devoid of laughs. At least for me.

At least Mr. Blandings Builds His Dream House is enjoyable in the early going, and stars Cary Grant and Myrna Loy, who previously starred together in Wings in the Dark (1935) and The Bachelor and the Bobby-Soxer (1947), and who are both attractive, charming, and a lot of fun to watch.

Grant plays Jim Blandings, a college graduate who lives in Manhattan, works in advertising, and makes about $15,000 a year. We learn all this from the film’s omniscient narrator, who also calls Mr. Blandings a “modern-day cliff dweller,” since he lives in a high-rise apartment building with his beautiful wife Muriel (Myrna Loy), their two daughters, and their housekeeper Gussie (Louise Beavers).

Grant plays Jim Blandings, a college graduate who lives in Manhattan, works in advertising, and makes about $15,000 a year. We learn all this from the film’s omniscient narrator, who also calls Mr. Blandings a “modern-day cliff dweller,” since he lives in a high-rise apartment building with his beautiful wife Muriel (Myrna Loy), their two daughters, and their housekeeper Gussie (Louise Beavers).

Here’s a case where inflation doesn’t tell you everything, since $15,000 is roughly $145,000 in 2012 dollars, but I don’t think even that salary today would be nearly enough to support a wife who doesn’t work, two kids in private school, and a Manhattan apartment big enough to fit a family and a live-in servant.

Granted, the Blandings live in cramped quarters. Everything in their apartment is full to bursting and ready to explode like Fibber McGee’s hall closet, and as the narrator tells us, “just getting shaved in the morning entitles a man to the Purple Heart.” But that’s just Manhattan living, folks. Even for the relatively well-to-do.

One day Mr. Blandings is enticed by a brochure from a Connecticut real estate firm that encourages him to “trade city soot for sylvan charm.”

I can’t even talk about what happens next. It’s just too painful.

I will say this, however. Mr. Blandings Builds His Dream House was funny enough to entertain even someone like me, and Mr. Blandings is presented as just enough of a screwball idiot to make his terrible decisions a little easier to laugh at. For instance, when his lawyer Bill Cole (Melvyn Douglas) asks what his engineer said about the foundation of the house he just purchased, Mr. Blandings responds, “Who needs engineers? This isn’t a train, you know.”