Detour (1945)

Directed by Edgar G. Ulmer

P.R.C.

There should be a picture of Tom Neal from the first few minutes of Detour next to the word “dejected” in the dictionary.

Unshaven, tie loosened, hat and suit rumpled, he walks along a California highway with his hands in his pockets, looking as though he just watched the world burn down to a cinder and he doesn’t know why he’s still standing.

Like a lot of film noirs, Edgar G. Ulmer’s Detour is told through flashback and voiceover narration. Sitting at a counter, a cup of coffee in front of him, Al Roberts (Neal) recalls his nothing-special but decent job playing piano in a Manhattan nightclub called the Break o’ Dawn, back when he had a clean jaw, a sharp tuxedo, and brilliantined hair.

“All in all I was a pretty lucky guy,” he says, recalling his romance with Sue Harvey (Claudia Drake), the singer in the club. Al has dreams of Carnegie Hall that he downplays with cynicism, while Sue dreams of making it in Hollywood. When she leaves New York to fulfill her dream, Al is still stuck in the club, performing virtuoso pieces for the occasional sawbuck tip from a drunk.

When Al decides he’s going to travel to Los Angeles to marry Sue, he has so little money that the only way he can do it is by thumbing rides. Hitchhiking in Detour isn’t the transcendent experience Jack Kerouac described in On the Road, it’s a grim necessity. “Ever done any hitchhiking? It’s not much fun, believe me,” Al says. “Oh, yeah, I know all about how it’s an education and how you get to meet a lot of people and all that, but me? From now on I’ll take my education in college, or in P.S. Sixty-Two, or I’ll send a dollar ninety-eight in stamps for ten easy lessons. Thumbing rides may save you bus fare, but it’s dangerous. You never know what’s in store for you when you hear the squeal of brakes. If only I’d known what I was getting into that day in Arizona.”

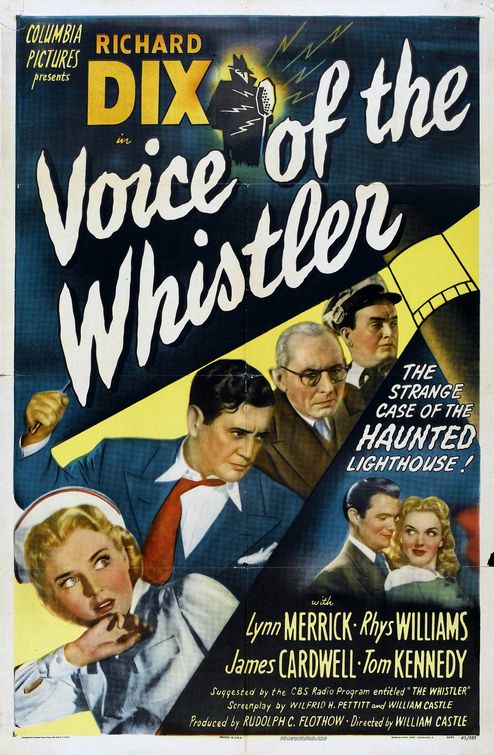

What’s in store for Al is one of the most brilliant film noirs ever made. The plot of Detour is not that different from any number of 30-minute radio plays produced for Suspense or The Whistler, and any devotee of the pulp novels of Cornell Woolrich or Jim Thompson will feel right at home while watching this film. So what is it that makes Detour so unique?

First, it’s phenomenal that such a finely crafted film was produced in just six days, and mostly in two locations; a hotel room and a car in front of a rear projection screen. Furthermore, it’s stunning how easy it is to suspend one’s disbelief during all of the driving scenes. Usually rear projection is a technique that draws attention to itself, and looks incredibly fake, but in Detour it’s just part of the background. It helps that the performances in the film are hypnotic. When Al is picked up by a man named Haskell (Edmund MacDonald), Haskell pops pills from his glove compartment and tells Al the story of how he got the deep scratches on his hand. “You know, there oughtta be a law against dames with claws,” he says. “I tossed her out of the car on her ear. Was I wrong? Give a lift to a tomato, you expect her to be nice, don’t you? After all, what kind of dames thumb rides? Sunday school teachers? The little witch. She must have thought she was riding with some fall guy.” As Haskell speaks, Al responds with noncommital little “Yep”s in a way that will be familiar to anyone who’s hitchhiked, or who’s had to sit next to a talkative creep on a Greyhound bus.

When Haskell drops dead under mysterious circumstances, Al is convinced he’ll be blamed for the murder if he reports it to the police, so he hides the corpse, switches clothes with Haskell, and takes his identification and money. His luck goes from bad to worse when he picks up a slovenly hitchhiker the next day named Vera (Ann Savage), who looks as if she’s “just been thrown off the crummiest freight train in the world.” Despite her plain looks, Al is immediately attracted to her. Unfortunately for him, Vera turns out to be the woman Haskell threw out of his car. She doesn’t recognize the car at first, and takes a nap after exchanging a few sullen words with Al. But after a minute or two, she bolts awake and says, “Where did you leave his body? Where did you leave the owner of this car? You’re not fooling anyone. This buggy belongs to a guy named Haskell. That’s not you, mister.”

The heartless Vera blackmails Al, forcing him to give her all of Haskell’s money and promise to get his hands on more, or she’ll turn him in to the cops. The two of them hole up in a lousy hotel room with a bedroom and a living room with a Murphy bed. Vera plays Al like a fiddle while getting drunk off cheap liquor and flinging abuse at him. Even so, the sexual tension between them is unbearable, which is even more remarkable considering that Savage is no great beauty, and plays the scene in which she attempts to seduce Al while wearing a bathrobe and a headscarf.

Like everything else in Detour, Neal and Savage’s performances are not Oscar-caliber, but they have an eerie power that can’t be fully explained. Neal, who was born into a wealthy family in Evanston, Illinois, was a former boxer with a Harvard law degree who played mostly tough guys in the movies. A troubled man, he was blackballed in Hollywood in 1951 after beating Franchot Tone to a pulp and giving him a concussion in a quarrel over the affections of Barbara Payton. And in 1965, Neal was tried in the shooting death of his wife Gale, and did time in prison for manslaughter.

Neal’s performance in this film is haunting, and invites a subjective judgment from the viewer. Are the things Al tells us about the deaths in the film accurate? Were they, as he claims, purely accidental? Or is he like every other murderer who pleads for clemency because it “wasn’t really my fault”? How real are the things we’re shown? Is Al really the unappreciated piano virtuoso he seems to be, or is this just another part of an elaborate fantasy world in which life refuses to hand him any breaks? This sense of nightmarish uncertainty and the pervading sense of doom make Detour one of the all-time great noirs. Edgar G. Ulmer was probably the best director who made films for the Poverty Row studio P.R.C., but Detour is head and shoulders above anything else I’ve ever seen of his.

If you’ve only seen the film adaptation of James M. Cain’s 1941 novel Mildred Pierce, you’re forgiven for never wondering whether the striking murder set piece that opens the film and informs the entire picture was an invention of the producer and the screenwriters that never occurred in the novel.

If you’ve only seen the film adaptation of James M. Cain’s 1941 novel Mildred Pierce, you’re forgiven for never wondering whether the striking murder set piece that opens the film and informs the entire picture was an invention of the producer and the screenwriters that never occurred in the novel. When The House on 92nd Street was released on DVD in 2005, it was as part of the “Fox Film Noir” collection. This is misleading, since it’s more of a docudrama than it is a noir. It’s a historically important film, however, since it was one of the first to feature location shooting for nearly all the exteriors, and one of the first to skillfully blend fact with fiction while presenting itself as essentially factual. (Charles G. Booth won an Academy Award for best original story for his work on this film.)

When The House on 92nd Street was released on DVD in 2005, it was as part of the “Fox Film Noir” collection. This is misleading, since it’s more of a docudrama than it is a noir. It’s a historically important film, however, since it was one of the first to feature location shooting for nearly all the exteriors, and one of the first to skillfully blend fact with fiction while presenting itself as essentially factual. (Charles G. Booth won an Academy Award for best original story for his work on this film.) Deanna Durbin is an absolute delight in this farcical murder mystery. Durbin, a native of Winnipeg, Manitoba, was once one of the biggest stars in Hollywood, but never made a movie after 1948. (She currently lives in a small village in France, grants no interviews, and is reportedly very happy.) In Lady on a Train, she plays a young woman named Nicki Collins. When the film begins, Collins is sitting by herself in a compartment on a train entering New York on an elevated line. She has come from San Francisco to spend the holidays with her wealthy businessman father, and is currently engrossed in a mystery novel called The Case of the Headless Bride. When the train is briefly delayed, she looks out the window of her train car and witnesses a murder. Through a lighted window, she sees a young man beat an older man to death with a crowbar. She never sees the murderer’s face, however, and when she reports the murder to the police, the desk sergeant dismisses her report as the product of the overheated imagination of a girl who loves murder mysteries and can provide no real specifics of where she was when she saw the murder. Also, it’s Christmas Eve, and who want to traipse around looking for a murder that may or may not have occurred somewhere in Manhattan north of Grand Central Station?

Deanna Durbin is an absolute delight in this farcical murder mystery. Durbin, a native of Winnipeg, Manitoba, was once one of the biggest stars in Hollywood, but never made a movie after 1948. (She currently lives in a small village in France, grants no interviews, and is reportedly very happy.) In Lady on a Train, she plays a young woman named Nicki Collins. When the film begins, Collins is sitting by herself in a compartment on a train entering New York on an elevated line. She has come from San Francisco to spend the holidays with her wealthy businessman father, and is currently engrossed in a mystery novel called The Case of the Headless Bride. When the train is briefly delayed, she looks out the window of her train car and witnesses a murder. Through a lighted window, she sees a young man beat an older man to death with a crowbar. She never sees the murderer’s face, however, and when she reports the murder to the police, the desk sergeant dismisses her report as the product of the overheated imagination of a girl who loves murder mysteries and can provide no real specifics of where she was when she saw the murder. Also, it’s Christmas Eve, and who want to traipse around looking for a murder that may or may not have occurred somewhere in Manhattan north of Grand Central Station? Lady on a Train is part mystery, part musical, part noir, part comedy, and part romance. The most surprising thing about this movie is that each element works perfectly, and they all complement one another. (Calling this film a noir is stretching it, but the final chase in a warehouse contains some striking chiaroscuro shot constructions, and is as tense as one could ask for.) Lady on a Train is also a delight for Durbin fetishists, since she has a different outfit and hairstyle in literally every scene. Sometimes the changes are subtle, but occasionally they’re impossible to miss, such as the scene in which she comes in out of the rain and is suddenly wearing gravity-defying, Pippi Longstocking-style braided pigtails.

Lady on a Train is part mystery, part musical, part noir, part comedy, and part romance. The most surprising thing about this movie is that each element works perfectly, and they all complement one another. (Calling this film a noir is stretching it, but the final chase in a warehouse contains some striking chiaroscuro shot constructions, and is as tense as one could ask for.) Lady on a Train is also a delight for Durbin fetishists, since she has a different outfit and hairstyle in literally every scene. Sometimes the changes are subtle, but occasionally they’re impossible to miss, such as the scene in which she comes in out of the rain and is suddenly wearing gravity-defying, Pippi Longstocking-style braided pigtails. Mary Beth Hughes appeared in dozens of films from 1939 onward as a second- or third-billed actress (including films in the Charlie Chan, Cisco Kid, and Michael Shayne series), but in director Sam Newfield’s P.R.C. production The Lady Confesses she gets to strut her limited but charming stuff in a lead role. A natural redhead, Hughes usually appeared onscreen as a platinum blonde. Her round cheeks, big eyes, and moxie made up for what she lacked as a thespian.

Mary Beth Hughes appeared in dozens of films from 1939 onward as a second- or third-billed actress (including films in the Charlie Chan, Cisco Kid, and Michael Shayne series), but in director Sam Newfield’s P.R.C. production The Lady Confesses she gets to strut her limited but charming stuff in a lead role. A natural redhead, Hughes usually appeared onscreen as a platinum blonde. Her round cheeks, big eyes, and moxie made up for what she lacked as a thespian. Edgar G. Ulmer was born in 1904 in Olmütz, Moravia, Austria-Hungary (now part of the Czech Republic). Like a number of talented German and Austrian directors, he moved to the United States in the ’20s and began working in Hollywood. Unlike better-known directors like Billy Wilder or Fritz Lang, however, Ulmer toiled in obscurity for most of his career, cranking out no-budget films. At least part of this was due to the fact that he was blackballed after he had an affair with Shirley Castle, who was the wife of B-picture producer Max Alexander, a nephew of powerful Universal president Carl Laemmle. Castle divorced Alexander and married Ulmer (becoming Shirley Ulmer), but the damage to Ulmer’s career was done. He spent most of the rest of his career churning out product for P.R.C. (Producers Releasing Corporation) Studios, one of the financially strapped Hollywood studios collectively referred to as “Poverty Row.”

Edgar G. Ulmer was born in 1904 in Olmütz, Moravia, Austria-Hungary (now part of the Czech Republic). Like a number of talented German and Austrian directors, he moved to the United States in the ’20s and began working in Hollywood. Unlike better-known directors like Billy Wilder or Fritz Lang, however, Ulmer toiled in obscurity for most of his career, cranking out no-budget films. At least part of this was due to the fact that he was blackballed after he had an affair with Shirley Castle, who was the wife of B-picture producer Max Alexander, a nephew of powerful Universal president Carl Laemmle. Castle divorced Alexander and married Ulmer (becoming Shirley Ulmer), but the damage to Ulmer’s career was done. He spent most of the rest of his career churning out product for P.R.C. (Producers Releasing Corporation) Studios, one of the financially strapped Hollywood studios collectively referred to as “Poverty Row.” Dick Powell was known as a song-and-dance man when he was cast as hard-boiled dick Philip Marlowe in this adaptation of Raymond Chandler’s novel Farewell, My Lovely.

Dick Powell was known as a song-and-dance man when he was cast as hard-boiled dick Philip Marlowe in this adaptation of Raymond Chandler’s novel Farewell, My Lovely.