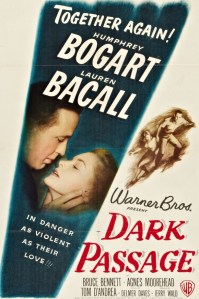

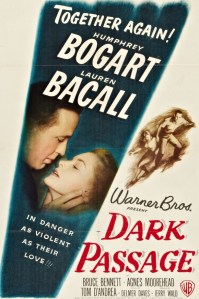

Delmer Daves’s Dark Passage is the red-headed stepchild of the Bogie-Bacall movies.

Delmer Daves’s Dark Passage is the red-headed stepchild of the Bogie-Bacall movies.

Humphrey Bogart and Lauren Bacall were married in 1945, and stayed married until Bogart’s death in 1957. They made four movies together — To Have and Have Not (1944), The Big Sleep (1946), Dark Passage, and Key Largo (1948). Of these four, Dark Passage is the strangest and the least widely acclaimed.

It was a bit of a critical and box office disappointment at the time of its release, possibly because Bogart’s face doesn’t actually appear on-screen until the picture is more than half over, and possibly because of Bogart’s involvement with the Committee for the First Amendment.

The Committee for the First Amendment was an organization that was formed to protest the treatment of Hollywood figures by the House Un-American Activities Committee. (Bogart later recanted his involvement with the organization in a letter published in the March 1948 issue of Photoplay entitled “I’m No Communist.”)

Dark Passage is based on a book by oddball crime novelist David Goodis. The film does a good job of bringing Goodis’s strong characterizations and nightmarish, occasionally surreal demimonde to the big screen.

For better or for worse, it also does a good job of bringing to life some of Goodis’s less powerful aspects, like his convoluted plots and his reliance on coincidence.

But just like the best of Goodis’s novels, the film version of Dark Passage doesn’t need to be plausible to work. It plays by its own rules, and when it works, boy does it work.

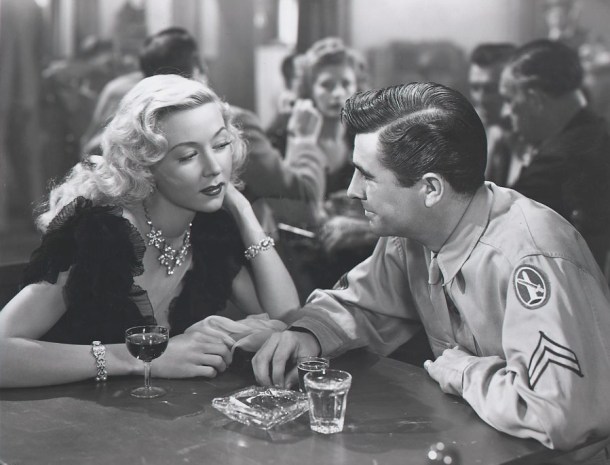

In Dark Passage, Bogart plays Vincent Parry, a man convicted of killing his wife who breaks out of San Quentin by hiding in a 55-gallon drum on the back of a flatbed truck. He manages to roll himself off the truck and into a ditch somewhere in Marin County. He strips down to his undershirt, buries his prison-issue shirt, and takes to the highway to thumb a ride. He’s picked up, first by a guy named Baker (Clifton Young), and then — when that little ride goes sour — by a beautiful artist named Irene Jansen (Lauren Bacall).

She hides him under her canvases and wet paint so they can make it through a roadblock at the entrance of the Golden Gate Bridge, then she takes him to her luxurious bachelorette pad in North Beach. Why is she helping him? Because her own father was unjustly imprisoned for a murder he didn’t commit, and because she followed Parry’s trial, even writing letters to the editor protesting his treatment by the press.

For the first 37 minutes of Dark Passage, Bogart’s face is never shown, for reasons we’ll get to in a moment. This P.O.V. style of filmmaking was pioneered by Robert Montgomery in his film Lady in the Lake (1947), but the technique works much better in Dark Passage, for a variety of reasons. First, the editing is more aggressive than in Lady in the Lake, which was essentially one long tracking shot designed to put the viewer in the shoes of the protagonist but that never quite worked. Second, there are third-person shots of Bogart in which his back is turned or his face is in shadows, which helps to break things up and make them more visually palatable.

Once Parry makes it to San Francisco, Dark Passage gets really weird. Irene gives him $1,000, new clothes and a hat, and a place to stay, but if you thought that qualified Parry as the luckiest escaped convict in history, you ain’t seen nothing yet.

He’s picked up one night by a cabbie named Sam (Tom D’Andrea), who not only recognizes him but believes Parry got a raw deal from the court system, and hooks him up with his buddy, Dr. Walter Coley, a plastic surgeon who can change his face.

Nervous about staying with Irene, Parry goes to see his friend George Fellsinger (Rory Mallinson), a trumpet player who gives Parry a key to his place. Incidentally, we get our first shot of Parry’s “real” face on the front of a newspaper laid across his friend George’s chest as he lies in bed. The real Parry has a mustache, and doesn’t look much like Bogart.

But he looks exactly like Bogart after his trip to see Dr. Coley, who’s played by 67-year-old actor Houseley Stevenson. Dr. Coley is the most ghoulishly fun character in Dark Passage. Wrinkled, liver-spotted, and chain-smoking, Dr. Coley asks Vincent if he’s ever seen a botched plastic surgery job right before he puts him under, and the kaleidoscopic nightmare Parry has while undergoing plastic surgery is a real standout.

Even after the surgery, we don’t fully see Bogart’s face until more than an hour into the picture.

Even after the surgery, we don’t fully see Bogart’s face until more than an hour into the picture.

Until then, he’s covered with bandages, smoking cigarettes with long filters and communicating with Irene using pencil and paper. (Throw a pair of shades on him and he’d look like Claude Rains in The Invisible Man).

While the plot may be contrived and coincidence-laden, the characterizations are sharp, and the actors are all really good. Lauren Bacall has to carry the film for much of the first hour, and she delivers a really good performance. She’s much better at interacting with the camera than any of the actors in Lady in the Lake were. Consequently, the P.O.V. technique draws less attention to itself, and works fairly well.

When the bandages finally come off, Parry looks at himself in the mirror and remarks, “Same eyes, same nose, same hair. Huh. Everything else seems to be in a different place. I sure look older. That’s all right, I’m not. And if it’s all right with me it oughtta be all right with you.”

When the bandages finally come off, Parry looks at himself in the mirror and remarks, “Same eyes, same nose, same hair. Huh. Everything else seems to be in a different place. I sure look older. That’s all right, I’m not. And if it’s all right with me it oughtta be all right with you.”

The fact that Bogart and Bacall were married in real life gives this line a little humorous subtext.

Hidden behind his new face, Parry is faced with another murder to solve, cops on his tail, a chiseler who hopes to blackmail Irene after he finds out she’s been shielding Parry, the presence of Irene’s old beau Bob (Bruce Bennett), and her shrill friend Madge Rapf (Agnes Moorehead), who keeps dropping by and nosing around.

That Parry goes about solving his problems in a haphazard, roundabout way should come as a surprise to no one who’s familiar with the fiction of David Goodis.

Dark Passage may not be a perfect film, but it’s an intriguing and involving one. Sid Hickox’s cinematography is gorgeous, and the location shooting in San Francisco is really effective. It’s worth seeing at least once, and if you’re like me, you’ll probably want to see it again.

The last of RKO’s four Dick Tracy pictures employs horror icon Boris Karloff to tell a hard-boiled crime story with a sci-fi twist.

The last of RKO’s four Dick Tracy pictures employs horror icon Boris Karloff to tell a hard-boiled crime story with a sci-fi twist.