A lot of people make a big deal of the fact that Black Narcissus was released the same year that India became an independent nation. The film, which was written, produced, and directed by Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger, is a sensuous, beautifully lensed Technicolor production. (Black Narcissus won two Academy Awards. Alfred Junge took home the award for best art direction and set direction in the color category and Jack Cardiff won the Oscar for best color cinematography.)

A lot of people make a big deal of the fact that Black Narcissus was released the same year that India became an independent nation. The film, which was written, produced, and directed by Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger, is a sensuous, beautifully lensed Technicolor production. (Black Narcissus won two Academy Awards. Alfred Junge took home the award for best art direction and set direction in the color category and Jack Cardiff won the Oscar for best color cinematography.)

The reason a lot of people make a big deal of its 1947 release is because a major theme of Black Narcissus is the inability of the British heart and mind to penetrate the mysteries of the Indian subcontinent. Deborah Kerr plays a young Anglican nun, Sister Clodagh, who is appointed Sister Superior of the Convent of the Order of the Servants of Mary, Calcutta. Not only does the convent occupy an abandoned harem high in the Himalaya mountains, but Sister Clodagh will be the youngest Sister Superior in the history of her order.

The plot of Black Narcissus isn’t as important as the mood the film creates, its scenery, or its overwhelming sense of lush sensuality.

Michael Powell wrote of Black Narcissus that it was the most erotic film he ever made. “It is all done by suggestion, but eroticism is in every frame and image, from the beginning to the end.”

None of this is to say that the eroticism of Black Narcissus is the only thing that makes it worth watching. It’s a fine character study and a well-acted story of the clash between fantasy and reality. But its visual textures, breathtaking scenery, and exquisite attention to detail are overwhelming.

Remarkably, Powell and Pressburger — who produced films together under the name “The Archers” — created all of their majestic Himalaya settings on the soundstages of Pinewood Studios. Usually matte paintings call attention to themselves and fool no one. In Black Narcissus they are seamlessly integrated into the rest of the film and are good enough to create a sense of vertigo in the scenes in which Sister Clodagh rings the enormous bell that hangs near the precipice on one side of the convent.

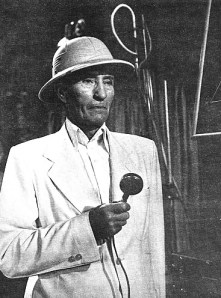

Black Narcissus is not a perfect film. While the performances are generally good, especially from Kerr as Sister Clodagh, David Farrar as the insouciant and charming British agent Mr. Dean, and Kathleen Byron as the unhinged Sister Ruth, the native characters are mostly played by British actors, which doesn’t always work. The 18-year-old English actress Jean Simmons is beautiful and beguiling as the dancing girl, Kanchi, but her light-colored eyes clash with her brown face makeup. Much less effective is May Hallatt as the deranged Angu Ayah, a servant inherited by the convent. Her screeching Cockney line delivery was so confusing that for most of the picture I wasn’t sure where her character was supposed to be from. (The only Indian actor in the film, Sabu, who plays the Young General, is from southern India, not northern India, where the film takes place.)

But these are minor quibbles. Black Narcissus is a stunningly beautiful film that I look forward to seeing again some day. Despite its sometimes outlandish story and its melodramatic elements, it’s a meticulously crafted piece of art from the greatest British directors of all time.