Jack Armstrong! Jack Armstrong! Jack Armstrong!

Jack Armstrong! Jack Armstrong! Jack Armstrong!

Jack Armstrong! The aaaaaaaaaaaaaaall-American boy!

If those words stir something deep within you, you’re probably either a child of the Depression or a freak like me who’s always liked to live in the past.

Beginning in 1933, the eponymous hero of Jack Armstrong, the All-American Boy traveled around the world with his uncle, Jim Fairfield, and his cousins, Betty and Billy Fairfield. The globetrotting quartet battled pirates, evil scientists, gangsters, and restive natives for 15 minutes on the radio every weekday. Sponsored by Wheaties, “the breakfast of champions,” Jack Armstrong gripped the nation’s youth with its blend of high adventure, glacial pacing, and repetitive storytelling until August 22, 1947, when it moved from a quarter-hour, five-day-a-week format to a 30-minute, twice-a-week broadcast.

Beginning in 1945, Jack, Betty, Billy, and Uncle Jim locked horns with the Silencer, a gangland leader who was at war with another crime lord, the Black Avenger. Eventually the Silencer was unmasked and revealed to be Victor Hardy, a brilliant scientist and inventor until a bout of amnesia led him to a life of evildoing (sort of like the Crime Doctor in reverse). After Hardy’s memory was restored, his lent his unique understanding of the criminal mind to Jack Armstrong and his crew. Uncle Jim was phased out of the program, and Vic Hardy became the adult overseer of the group, as well as head of the “Scientific Bureau of Investigation,” or SBI. In 1950, the Jack Armstrong program finally ended and Jack, Betty, and Billy were suddenly grown-ups, heard in a new 30-minute, twice-a-week series called Armstrong of the SBI. The all-American adult version of Jack didn’t last long, though, and Armstrong of the SBI went off the air June 28, 1951.

Wallace Fox’s Jack Armstrong is a 15-part serial from Columbia Pictures. All the major characters from the radio play are present (including both Uncle Jim and Vic Hardy), but after a promising first chapter, the serial devolves into repetitious tangles with “natives” on an island somewhere. I don’t know where the island is supposed to be, but I imagine it’s flying distance from California, since Jack Armstrong and the gang get there in a twin-engine plane. One of the bad guys refers to it as “point X,” and the third chapter of Jack Armstrong is called “Island of Deception,” but I think those are both descriptors, not proper names, so let’s just call it “Crazy Island,” shall we?

Wallace Fox’s Jack Armstrong is a 15-part serial from Columbia Pictures. All the major characters from the radio play are present (including both Uncle Jim and Vic Hardy), but after a promising first chapter, the serial devolves into repetitious tangles with “natives” on an island somewhere. I don’t know where the island is supposed to be, but I imagine it’s flying distance from California, since Jack Armstrong and the gang get there in a twin-engine plane. One of the bad guys refers to it as “point X,” and the third chapter of Jack Armstrong is called “Island of Deception,” but I think those are both descriptors, not proper names, so let’s just call it “Crazy Island,” shall we?

In this serial, Jack Armstrong is an all-American “boy” in name only, since the actor who plays him, John Hart, was 28 or 29 during filming, and looked about 30. Hart’s dark good looks and slicked-back hair make him look as if he’d be more comfortable romancing a movie producer’s wife on the dance floor of the Cocoanut Grove nightclub than building a nifty jet engine car with his little buddy Billy (Joe Brown), which is what he’s doing when we meet him in the first chapter of the serial, “Mystery of the Cosmic Ray.”

Billy Fairfield is the obligatory horse-faced, comic-relief sidekick. With his bug eyes and big teeth, Brown looks like Mickey Rooney standing in a wind tunnel. He’s obsessed with food, and most of the “humor” in Jack Armstrong comes from his “But when are we going to eat?” quips. Billy’s sister Betty is played by Miss America 1941, Rosemary La Planche, whom I’ve found delightful in every role I’ve seen her in prior to this. In Jack Armstrong, however, she has the same consternated look on her face in every scene, and is forced to wear an unflattering gray sweat suit that makes her look as if she’s suffering through Army PT.

Jack’s jet engine car has no carburetor, no cylinders, no distributor, and can go 50 miles per hour faster than any other car on the road. Jack never explains why it’s riveted, not welded, or how he can hang outside of it during a high-speed chase without getting his hair mussed, but the action in the first chapter is fast-paced enough that I didn’t really care. (And for my money, sped-up films of car chases never get old.)

I was hoping for lots more high-speed action, but after Uncle Jim (Pierre Watkin), the owner of the Fairfield Aviation Co., announces that they’ve picked up unknown cosmic rays, possibly from another country, he and Jack, Betty, and Billy are off to Crazy Island in the second chapter of the serial, “The Far World,” and things get pretty dull.

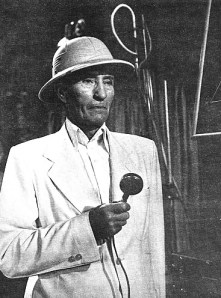

Most of Jack’s time on Crazy Island is spent squaring off against evil mastermind Jason Grood, who’s played by Charles Middleton, the man who played Ming the Merciless in the Flash Gordon serials of the ’30s. Remarkably, he’s just as odd-looking without any of his Ming makeup.

Grood kidnaps Vic Hardy (Hugh Prosser) and forces him to work with his henchman, Prof. Hobart Zorn (Wheeler Oakman), who’s discovered a power “several steps above atomic energy,” which they use to create a “cosmic beam annihilator.” Grood sends the cosmic beam into space as part of his “aeroglobe,” which he explains in the following, 100% scientific fashion: “Where the pull of gravity from the sun and outer solar planets equalizes the pull of earth gravity, there you have ‘zero gravity,’ creating a ‘space platform.’ On this, our aeroglobe rests.”

With the ability to train his cosmic beam annihilator at any spot on earth, Grood plans to hold all the nations of the world hostage. While attempting to foil Grood on Crazy Island, Jack, Uncle Jim, Billy, and Betty face the Pit of Everlasting Fire, escape from quicksand, tangle with angry natives, and are helped by friendly natives led by the sexy and beautiful Princess Alura (Claire James). I honestly couldn’t tell the unfriendly natives from the friendly natives. They all have black page-boy haircuts, wear Madras shirts and sarongs, and look about as “native” as Boris Karloff.

Jack Armstrong suffers from poorly staged action and several cliffhangers that are truly awful. In one, bad guy Gregory Pierce (John Merton) is zapped by an intruder alert field. Are we supposed to care about him? Another chapter ends with Jack and a bad guy rolling down a gentle incline while hitting each other. Not exactly “the jaws of death.”

Plausibility, scientific accuracy, and believable dialogue were never requirements for a good serial, but excitement and fun were, and Jack Armstrong suffers from a lack of both.