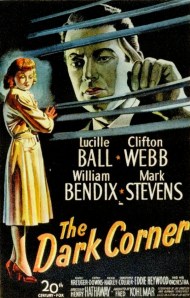

If someone were to say to me, “What exactly is a film noir? I don’t think I’ve ever seen one,” I might direct them to Henry Hathaway’s The Dark Corner. Not because it’s the greatest noir I’ve ever seen, but because it contains so many “noir” elements; a tough-talking P.I. and his sexy secretary, blackmail, frame-ups, violence, creative use of shadows and low-angle shots, and a plethora of quotable tough-guy dialogue like “I can be framed easier than Whistler’s mother.” It’s also not a picture that’s attained the status of a true “classic” like Double Indemnity (1944) or The Big Sleep (1946), so no one’s going to be distracted by great acting, iconic characterizations, or a brilliant storyline. This is pulp. Pure and unvarnished.

If someone were to say to me, “What exactly is a film noir? I don’t think I’ve ever seen one,” I might direct them to Henry Hathaway’s The Dark Corner. Not because it’s the greatest noir I’ve ever seen, but because it contains so many “noir” elements; a tough-talking P.I. and his sexy secretary, blackmail, frame-ups, violence, creative use of shadows and low-angle shots, and a plethora of quotable tough-guy dialogue like “I can be framed easier than Whistler’s mother.” It’s also not a picture that’s attained the status of a true “classic” like Double Indemnity (1944) or The Big Sleep (1946), so no one’s going to be distracted by great acting, iconic characterizations, or a brilliant storyline. This is pulp. Pure and unvarnished.

I love pulpy noir, so I really enjoyed The Dark Corner. On the other hand, I first saw this movie less than a decade ago, and only remembered one scene, in which one character pushes another out of a skyscraper window and then calmly walks to his dentist appointment. I have pretty good recall, especially when it comes to films, but I didn’t remember anything about this movie, not even after watching it again. Nothing came back. And I have a feeling that I won’t remember much about it 10 years from now, either.

But that doesn’t change the fact that I enjoyed the heck out of it while I was watching it. Mark Stevens isn’t an actor who ever made a big impression on me, but he’s a passable lead. As private investigator Bradford Galt, he delivers his lines with the speed and regularity of a gal in the steno pool pounding the keys of a Smith Corona typewriter. Galt is the kind of guy who makes himself a cocktail by grabbing two bottles with one hand and pouring them into a highball glass together. He’s also the kind of guy who probably wouldn’t do well in today’s litigious corporate environment. When he tells his newly hired secretary Kathleen Stewart (Lucille Ball) that he’s taking her out on a date, she asks, “Is this part of the job?” He responds, “It is tonight.”

It turns out that he’s (mostly) telling the truth, and the reason he’s taking her out on the town is to draw out a tail he’s spotted; a big mug in a hard-to-miss white suit played by William Bendix. Their date was one of my favorite sequences in the movie. There’s a lot of great location footage of New York in The Dark Corner, but the scenes in the Tudor Penny Arcade take the cake. I don’t know if any of the scenes in the arcade were shot in back lots, but the batting cages, the Skeebowl, and the coin-operated Mutoscopes with titles like “Tahitian Nights” and “The Virgin of Bagdad” all looked pretty authentic.

Once Galt gets his hands on the guy tailing him and roughs him up for information, the plot kicks into gear. Bendix’s character, “Fred Foss,” is a heavy who claims to have been hired by a man named Jardine. Galt starts to panic as soon as he hears the name. Jardine was Galt’s partner when he was a P.I. in San Francisco. Jardine had Galt framed, which led to Galt doing two years in the pokey. Jardine (played by the blond, German-accented Kurt Kreuger) is now in New York, but still up to his old tricks, seducing married women and running blackmail schemes. The current object of his affection, Mari Cathcart (Cathy Downs), is married to the effete art dealer Hardy Cathcart, who is played by Clifton Webb. In The Dark Corner, Webb essentially reprises his role from Otto Preminger’s Laura (1944); another film noir in which a painting of a beautiful brunette played a major role.

I won’t summarize the Byzantine plot any further, but it should go without saying that all the pieces tie together. As I said, The Dark Corner isn’t the greatest noir I’ve ever seen, but it’s pretty enjoyable to watch, and it looks fantastic. The dialogue is especially cracking, and consistently verges on the ridiculous. For instance, when Cathcart tells Foss (who is on the phone with Galt) to tell Galt that he wants $200 to leave town, Foss repeats the information to Galt by saying, “I need two yards. Powder money.”