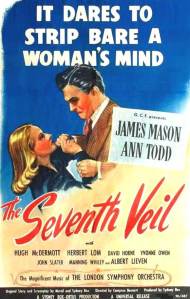

Compton Bennett’s film The Seventh Veil premiered in London on October 18, 1945. It was the biggest box office success of the year in Britain. The first record of its showing in the United States I can find is on Christmas day, 1945, in New York City. It went into wide release in the U.S. on February 15, 1946, and won an Academy Award the next year for best original screenplay. The story and script were by Sydney and Muriel Box. Sydney Box also produced the film.

Compton Bennett’s film The Seventh Veil premiered in London on October 18, 1945. It was the biggest box office success of the year in Britain. The first record of its showing in the United States I can find is on Christmas day, 1945, in New York City. It went into wide release in the U.S. on February 15, 1946, and won an Academy Award the next year for best original screenplay. The story and script were by Sydney and Muriel Box. Sydney Box also produced the film.

The title refers to the seven veils that Salomé peeled away in history’s most famous striptease. As Dr. Larsen (Herbert Lom) explains to his colleagues, “The human mind is like Salomé at the beginning of her dance, hidden from the outside world by seven veils. Veils of reserve, shyness, fear. Now, with friends the average person will drop first one veil, then another, maybe three or four altogether. With a lover, she will take off five. Or even six. But never the seventh. Never. You see, the human mind likes to cover its nakedness, too, and keep its private thoughts to itself. Salomé dropped her seventh veil of her own free will, but you will never get the human mind to do that.”

The mind Dr. Larsen is attempting to strip bare is that of Francesca Cunningham (Ann Todd), a concert pianist who has lost the will to live, and who has been hospitalized after a suicide attempt. For the first hour of the film, her psychoanalytic sessions with Dr. Larsen act mostly as a framing device for Francesca’s flashbacks, but by the end, the high-minded hooey is laid on nearly as thick as it is in Alfred Hitchcock’s contemporaneous film Spellbound.

In her first flashback, Francesa recalls her schoolgirl days with her friend Susan Brook (Yvonne Owen). Susan’s insouciance towards academics is responsible for both of them being late to class one too many times. If Susan is punished, we don’t see it. Francesca’s punishment, however, will have dire ramifications. Brutally beaten across the backs of her hands with a ruler on the morning of her scholarship recital, she blows it completely, and is so devastated she gives up the piano.

When she is orphaned at the age of 17, Francesca is taken in by her uncle Nicholas (James Mason), a man whom she barely knows. She learns that the term “uncle” is a misnomer, since Nicholas is actually her father’s second cousin. Interestingly, both Mason and Todd were 36 years old when they appeared in this film. Their lack of an age difference isn’t too distracting, though. Todd has a wan, ethereal visage that lends itself to playing young, and Mason’s dark, Mephistophelian countenance is eternally middle-aged and handsome.

Nicholas is a confirmed bachelor who walks with a slight limp and hates women. He is also a brilliant music teacher, although his own skills as a musician are only average. Under his sometimes cruel tutelage, Francesca practices four to five hours a day, and eventually becomes an accomplished musician. Nicholas’s control over her comes at a cost. While she is studying at the Royal College of Music, Francesca falls in love with an American swing band leader named Peter Gay (Hugh McDermott). When Francesca tells Nicholas that she is engaged, he refuses to give his consent, since she has not yet reached her age of majority (in this case, 21), and tells her she will leave with him for Paris immediately. She does so, and continues her education in Europe.

For a melodrama, The Seventh Veil manages to be fairly gripping, especially if you find depictions of live performances stressful. When Francesca makes her debut with the London Symphony Orchestra (conducted by Muir Mathieson), performing Rachmaninoff’s Piano Concerto No. 2 in C minor and Grieg’s Piano Concerto in A minor, the film cuts between Francesca sitting at the piano, her hands (doubled by the pianist Eileen Joyce), Nicholas standing offstage, and her old friend Susan, who is in the front row. Not only does Susan, now a wealthy socialite, enter late and talk during the performance, but her mere presence reminds Francesca so strongly of the brutal whipping her hands received as a girl that the act of playing becomes almost too much to bear. She makes it through the performance, but when she rises to bow, she collapses from sheer exhaustion.

Francesca’s next trial — and the one that will result in her institutionalization — comes when Nicholas hires an artist named Maxwell Leyden (Albert Lieven) to paint her portrait. Francesca and Maxwell fall in love and go away to live together, despite Nicholas’s violent objections, but after a car accident, Francesca becomes convinced that her hands are irreparably damaged and she will never play again. Dr. Larsen, however, tells her there is nothing physically wrong with her, and he makes it his mission to cure her.

In the end, it is a recording of the simple, beautiful melody of the second movement of Beethoven’s Piano Sonata No. 8, “Pathétique,” along with a good old-fashioned session of hypnosis, that frees Francesca from her mental prison. The climax of the film does not hinge on whether or not she will perform again, however. It hinges on which of the three men in her life she will end up with; Peter, Maxwell, or Nicholas.

As soon as her choice is made, the film ends. There is no depiction of consequences. How satisfying the viewer finds the ending partly depends on which male character they like best, I suppose, although there are other considerations, such as how one feels about the question of whether it is better to be a great artist or to be happy, or even if Francesca can have one without the other. Personally, I found it all a bit ridiculous, but I enjoyed the film overall.

Pursuit to Algiers, the twelfth film to star Basil Rathbone as Sherlock Holmes and Nigel Bruce as his boon companion Dr. John H. Watson, is a minor entry in the series, but a thoroughly enjoyable one. It’s the ninth Holmes picture directed by Roy William Neill, and his sure hand and professionalism are fully in evidence.

Pursuit to Algiers, the twelfth film to star Basil Rathbone as Sherlock Holmes and Nigel Bruce as his boon companion Dr. John H. Watson, is a minor entry in the series, but a thoroughly enjoyable one. It’s the ninth Holmes picture directed by Roy William Neill, and his sure hand and professionalism are fully in evidence. Republic Pictures is the unassailable king of the cliffhangers after the silent era. Most of the best chapterplays of the ’30s and ’40s were Republic productions. Dick Tracy (1937), The Lone Ranger (1938), Zorro’s Fighting Legion (1939), Adventures of Red Ryder (1940), Mysterious Doctor Satan (1940), Adventures of Captain Marvel (1941), Jungle Girl (1941), Spy Smasher (1942), Perils of Nyoka (1942), The Masked Marvel (1943), and Captain America (1944) are just a few of the more than sixty serials produced by Republic Pictures, most of which are still incredibly entertaining. The best Republic serials combined wild action and elaborate stunts with nicely paced stories that could be strung out over 12 to 15 weekly installments with a few subplots here and there, but nothing too complicated or that viewers couldn’t pick up with in the middle. Each chapter ended with a cliffhanger (like Captain Marvel flying toward a woman falling off a dam, or a wall of fire rushing down a tunnel toward Spy Smasher). The next week’s chapter would begin with a minute or two of the previous week’s climax and the resolution, and the cycle would repeat until the final chapter.

Republic Pictures is the unassailable king of the cliffhangers after the silent era. Most of the best chapterplays of the ’30s and ’40s were Republic productions. Dick Tracy (1937), The Lone Ranger (1938), Zorro’s Fighting Legion (1939), Adventures of Red Ryder (1940), Mysterious Doctor Satan (1940), Adventures of Captain Marvel (1941), Jungle Girl (1941), Spy Smasher (1942), Perils of Nyoka (1942), The Masked Marvel (1943), and Captain America (1944) are just a few of the more than sixty serials produced by Republic Pictures, most of which are still incredibly entertaining. The best Republic serials combined wild action and elaborate stunts with nicely paced stories that could be strung out over 12 to 15 weekly installments with a few subplots here and there, but nothing too complicated or that viewers couldn’t pick up with in the middle. Each chapter ended with a cliffhanger (like Captain Marvel flying toward a woman falling off a dam, or a wall of fire rushing down a tunnel toward Spy Smasher). The next week’s chapter would begin with a minute or two of the previous week’s climax and the resolution, and the cycle would repeat until the final chapter. The first film serial featuring Secret Agent X-9 was made by Universal in 1937, and starred Scott Kolk as Agent X-9, a.k.a. “Dexter,” who sought to recover the crown jewels of Belgravia from a master thief called “Blackstone.” The second featured a boyish-looking 32-year-old Lloyd Bridges as Agent X-9, a.k.a. “Phil Corrigan.” Made toward the end of World War II, the 1945 iteration of the character focused on wartime intrigue and Corrigan’s cat-and-mouse games with Axis spies. Taking a cue from Casablanca (1942), the serial was set in a neutral country called “Shadow Island,” in which Americans, Japanese, Chinese, French, Germans, Australians, and the seafaring riffraff of the world freely intermingle. A fictional island nation off the coast of China, “Shadow Island” has a de facto leader named “Lucky Kamber” (Cy Kendall) who owns a bar called “House of Shadows” and has a finger in every pie, including gambling and espionage. Various German and Japanese military officers, secret agents, and thugs run amuck in this serial, but the one who most stands out is the unfortunately made-up and attired Victoria Horne as “Nabura.” In her role as a Japanese spymaster, Horne is outfitted with eyepieces that cover her upper eyelids, appearing to drag them down from sheer weight. She doesn’t look Asian, she just looks as if her eyes are closed.

The first film serial featuring Secret Agent X-9 was made by Universal in 1937, and starred Scott Kolk as Agent X-9, a.k.a. “Dexter,” who sought to recover the crown jewels of Belgravia from a master thief called “Blackstone.” The second featured a boyish-looking 32-year-old Lloyd Bridges as Agent X-9, a.k.a. “Phil Corrigan.” Made toward the end of World War II, the 1945 iteration of the character focused on wartime intrigue and Corrigan’s cat-and-mouse games with Axis spies. Taking a cue from Casablanca (1942), the serial was set in a neutral country called “Shadow Island,” in which Americans, Japanese, Chinese, French, Germans, Australians, and the seafaring riffraff of the world freely intermingle. A fictional island nation off the coast of China, “Shadow Island” has a de facto leader named “Lucky Kamber” (Cy Kendall) who owns a bar called “House of Shadows” and has a finger in every pie, including gambling and espionage. Various German and Japanese military officers, secret agents, and thugs run amuck in this serial, but the one who most stands out is the unfortunately made-up and attired Victoria Horne as “Nabura.” In her role as a Japanese spymaster, Horne is outfitted with eyepieces that cover her upper eyelids, appearing to drag them down from sheer weight. She doesn’t look Asian, she just looks as if her eyes are closed. Apparently populist rage against pharmaceutical giants is nothing new. In Strange Confession, the fifth of six “Inner Sanctum Mysteries” produced by Universal Pictures and released from 1943 to 1945, Lon Chaney, Jr. plays a brilliant chemist named Jeff Carter whose life goes from bad to worse when he twice accepts employment from the unscrupulous owner of the largest medical distributing company in an unnamed American city.

Apparently populist rage against pharmaceutical giants is nothing new. In Strange Confession, the fifth of six “Inner Sanctum Mysteries” produced by Universal Pictures and released from 1943 to 1945, Lon Chaney, Jr. plays a brilliant chemist named Jeff Carter whose life goes from bad to worse when he twice accepts employment from the unscrupulous owner of the largest medical distributing company in an unnamed American city. Deanna Durbin is an absolute delight in this farcical murder mystery. Durbin, a native of Winnipeg, Manitoba, was once one of the biggest stars in Hollywood, but never made a movie after 1948. (She currently lives in a small village in France, grants no interviews, and is reportedly very happy.) In Lady on a Train, she plays a young woman named Nicki Collins. When the film begins, Collins is sitting by herself in a compartment on a train entering New York on an elevated line. She has come from San Francisco to spend the holidays with her wealthy businessman father, and is currently engrossed in a mystery novel called The Case of the Headless Bride. When the train is briefly delayed, she looks out the window of her train car and witnesses a murder. Through a lighted window, she sees a young man beat an older man to death with a crowbar. She never sees the murderer’s face, however, and when she reports the murder to the police, the desk sergeant dismisses her report as the product of the overheated imagination of a girl who loves murder mysteries and can provide no real specifics of where she was when she saw the murder. Also, it’s Christmas Eve, and who want to traipse around looking for a murder that may or may not have occurred somewhere in Manhattan north of Grand Central Station?

Deanna Durbin is an absolute delight in this farcical murder mystery. Durbin, a native of Winnipeg, Manitoba, was once one of the biggest stars in Hollywood, but never made a movie after 1948. (She currently lives in a small village in France, grants no interviews, and is reportedly very happy.) In Lady on a Train, she plays a young woman named Nicki Collins. When the film begins, Collins is sitting by herself in a compartment on a train entering New York on an elevated line. She has come from San Francisco to spend the holidays with her wealthy businessman father, and is currently engrossed in a mystery novel called The Case of the Headless Bride. When the train is briefly delayed, she looks out the window of her train car and witnesses a murder. Through a lighted window, she sees a young man beat an older man to death with a crowbar. She never sees the murderer’s face, however, and when she reports the murder to the police, the desk sergeant dismisses her report as the product of the overheated imagination of a girl who loves murder mysteries and can provide no real specifics of where she was when she saw the murder. Also, it’s Christmas Eve, and who want to traipse around looking for a murder that may or may not have occurred somewhere in Manhattan north of Grand Central Station? Lady on a Train is part mystery, part musical, part noir, part comedy, and part romance. The most surprising thing about this movie is that each element works perfectly, and they all complement one another. (Calling this film a noir is stretching it, but the final chase in a warehouse contains some striking chiaroscuro shot constructions, and is as tense as one could ask for.) Lady on a Train is also a delight for Durbin fetishists, since she has a different outfit and hairstyle in literally every scene. Sometimes the changes are subtle, but occasionally they’re impossible to miss, such as the scene in which she comes in out of the rain and is suddenly wearing gravity-defying, Pippi Longstocking-style braided pigtails.

Lady on a Train is part mystery, part musical, part noir, part comedy, and part romance. The most surprising thing about this movie is that each element works perfectly, and they all complement one another. (Calling this film a noir is stretching it, but the final chase in a warehouse contains some striking chiaroscuro shot constructions, and is as tense as one could ask for.) Lady on a Train is also a delight for Durbin fetishists, since she has a different outfit and hairstyle in literally every scene. Sometimes the changes are subtle, but occasionally they’re impossible to miss, such as the scene in which she comes in out of the rain and is suddenly wearing gravity-defying, Pippi Longstocking-style braided pigtails.