When it comes to Poverty Row westerns, there’s a fine line between watchable and unwatchable.

When it comes to Poverty Row westerns, there’s a fine line between watchable and unwatchable.

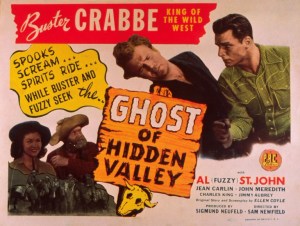

I didn’t dislike Ghost of Hidden Valley, and even enjoyed a lot of it. I can’t say whether that’s because it’s a slight cut above other Poverty Row westerns distributed by P.R.C. (Producers Releasing Corporation) that I’ve seen lately, or because my expectations were ground down to a nub by the three other movies directed by Sam Newfield that I’ve watched in the past year.

One of the most prolific directors of all time, Newfield directed more than 250 movies in a career that spanned almost 40 years. Martin Scorsese once said, “Newfield is hard, that’s a hard one, you can’t do too much of that.” This from a man well known for his insatiable appetite for films of all kinds.

Ghost of Hidden Valley begins with some stock footage of an enormous herd of cattle. In the next scene, Ed “Blackie” Dawson (Charles King), the leader of a group of cattle rustlers, shoots an interloper so he won’t tell any tales to the law. “Well, that takes care of that,” Dawson’s henchman says. “The ghost of hidden valley will get all the blame.”

I’m a fan of economical storytelling, even when it’s outlandish.

There is no ghost, of course, and we won’t see any more cattle, either. There will be some weak-sauce comedy in which the grizzled and toothless Fuzzy Q. Jones (Al “Fuzzy” St. John) will mistake the calls of a hoot owl for the spectral cries of a wandering spirit, but that’s it.

After Dawson and his rustlers commit murder, we see cowboy Billy Carson (Buster Crabbe) and his friend Fuzzy at the post office in Canyon City, Arizona. Fuzzy has received a letter from someone named Cecil Trenton. (It comes addressed to “Fuzzy Jones, Esq.”) Cecil’s late brother, Sir Dudley Trenton, spoke well of Fuzzy, as well as his sojourn in America generally. “It was his wish that his son Henry, a young gentleman just out of Oxford, should experience a bit of the rugged life and devote some attention to the property Sir Dudley purchased in your vicinity,” Cecil writes.

“What is this Oxford he just got out of, a penitentiary?” asks Fuzzy.

“No,” Billy responds. “Some sort of a school.”

Henry Trenton (John Meredith) is exactly what you might expect. A fey, snooty-accented tenderfoot wearing a checked shirt, vest, ten-gallon hat, and ridiculous sheepskin chaps. “I always make it a point to dress correctly,” he says. He even has an aristocratic butler in tow named Tweedle (Jimmy Aubrey).

Billy sees the potential of Hidden Valley Ranch, if only someone could knuckle down and work it properly. Will Henry Trenton be that man?

Ghost of Hidden Valley is a typical P.R.C. western, with plenty of shootouts, chases on horseback, and furniture-destroying fistfights to fill out its 56-minute running time, but at least it’s briskly paced. Also, the female lead (Jean Carlin) is pretty, unlike the last Crabbe P.R.C. western I saw, and the script by Ellen Coyle is breezy and relatively entertaining.

There’s still Newfield’s trademark sloppiness and inattention to detail for the viewer to contend with. For instance, there’s one scene in which Crabbe’s skinny stunt double, his loose shirt hanging out of his pants, takes a punch, there’s a cut, and the next shot is of the real Crabbe, his chunky torso unmistakable, and his shirt tightly tucked into his jeans.

Crabbe was my main problem with this film. No longer the dashing young actor he was when he played Flash Gordon in the ’30s, Crabbe phones in his performance, has trouble mounting his horse in at least one scene, and generally looks as if he’d rather be somewhere else.