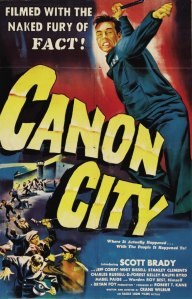

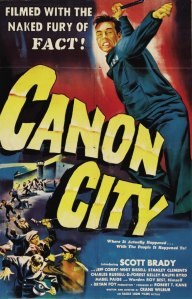

Crane Wilbur’s Canon City is a low-budget entry in the docudrama genre, a genre that began in 1945 with the Louis de Rochemont-produced espionage melodrama The House on 92nd Street and enjoyed enormous popularity in post-war Hollywood.

Crane Wilbur’s Canon City is a low-budget entry in the docudrama genre, a genre that began in 1945 with the Louis de Rochemont-produced espionage melodrama The House on 92nd Street and enjoyed enormous popularity in post-war Hollywood.

Docudramas were dramatizations of actual events that featured actors but that strove for authenticity by filming in actual locations, using real documents in key scenes, and featuring participants in the case playing themselves in bit parts.

After The House on 92nd Street followed more fact-based spy thrillers like 13 Rue Madeleine (1947) and The Iron Curtain (1948), and legal docudramas like Boomerang (1947) and Call Northside 777 (1948).

Some films, like Kiss of Death (1947), T-Men (1947), and The Naked City (1948), were mostly fictional, but were presented in a docudrama fashion and filmed on location to add authenticity to otherwise run-of-the-mill crime stories.

Canon City uses a combination of docudrama techniques. It begins in a straightforward documentary style, and slowly draws us into the fictional world of its incarcerated protagonists. The obligatory scroll of text that opens the film informs the viewer that all events depicted in the film are based on actual events that took place in and around the Colorado State Prison in Canon City on the night of December 30, 1947. (Canon City is pronounced “Canyon City,” and is sometimes spelled Cañon City.) It goes on to say that the convicts shown in the film are the actual convicts involved in the case, and that Roy Best, the warden of the prison, plays himself. Finally, we are told that “the details of the break are portrayed exactly as they occurred and were photographed where they happened.”

Reed Hadley narrates the opening in his signature style (docudramas provided a lot of work for Hadley). He describes the Colorado State Penitentiary in Canon City as “a home for those who like to have their own way too much, and have taken forbidden steps to achieve their aims. All kinds are here; murderers, kidnappers, thieves, robbers, embezzlers.”

Warden Best and the disembodied voice of Hadley lead the viewer on a tour of the prison, introducing the variety of work that the prisoners do and conducting short interviews with actual inmates of various types; a man soon to be paroled, an old man who’s been doing time since 1897, a 14-year-old murderer sentenced to 20-30 years who’s working on a hooked rug in the art shop, and a murderer whose death sentence was commuted to life by the warden, and who now hopes to be paroled in 1949.

We then see the process of nighttime lockdown, and at the 9-minute mark of the film Hadley’s narration introduces the viewer to a pair of inmates with adjoining cells: Jim Sherbondy, a 29-year-old inmate who was sentenced at the age of 17 for killing a police officer, and Johnson, a long-termer who is working on the model of a ship. (His real work — a zip gun — is hidden behind the ship. He’s part of a plan to break out.)

Hadley’s narration doesn’t stop after Sherbondy and Johnson are introduced, and the film continues in a semi-documentary style, but the introduction of these two characters marks the moment when the film moves from fact to fiction. Remember that opening text from the beginning of the film I mentioned? The one that said “The convicts you will see are the actual convicts”?

Hadley’s narration doesn’t stop after Sherbondy and Johnson are introduced, and the film continues in a semi-documentary style, but the introduction of these two characters marks the moment when the film moves from fact to fiction. Remember that opening text from the beginning of the film I mentioned? The one that said “The convicts you will see are the actual convicts”?

Well, this was clearly a lie, since Sherbondy and Johnson are both played by actors, not actual convicts. This is par for the course, though. Despite what they invariably claimed, docudramas in the ’40s usually had a tricky relationship with the truth.

I couldn’t figure out who the uncredited actor who plays Johnson is (if you know, please comment on this review), but Sherbondy is played by Scott Brady, the younger brother of notorious tough-guy actor Lawrence Tierney. (Lawrence Tierney and Scott Brady’s youngest brother, Edward Tierney, who turned 20 years old in 1948, also had a career in the movies starting in the ’50s.) Brady was born Gerard Kenneth Tierney, and Canon City was his first major film acting role, and the first film in which he was credited as “Scott Brady.” (His first appearance was a small role in Sam Newfield’s 1948 film The Counterfeiters, in which he was credited as “Gerard Gilbert.”)

Brady bears an uncanny resemblance to his older brother, but his face is a little softer and more innocent-looking, which works well for his role in Canon City. Sherbondy is a reluctant participant in the breakout. He has a job in the prison’s photography shop working in the darkroom, which is the perfect place for the conspirators to hide a load of zip guns, since the darkroom requires guards to wait outside until it’s safe to turn the lights on and open the door.

I wonder if anyone who saw Canon City during its initial theatrical run noticed Brady’s resemblance to Lawrence Tierney, or if there were any astute viewers who noticed the slim, bespectacled Whit Bissell and said to themselves, “Hey, wasn’t that guy in Brute Force?”

I also wonder how many viewers didn’t specifically recognize any of the actors but were able to tell that they were watching actors and not the actual participants in the case. And if they did, did they feel cheated after the opening claim of total and complete veracity?

I wonder these things because I do think that Canon City is remarkably skillful in the way it draws the viewer in and the way it manages to feel raw and real throughout. A little before the half-hour mark, the breakout kicks into high gear with an assault on a guard and a furious rush to fit all the pieces of the plan together. For nearly an hour, Canon City is as tense a picture as one could ask for. A dozen men pour out into a snowy night, disguised as prison guards. The prison alarm tolls throughout the small town. Terrified moviegoers swarm out of a theater whose marquee shows the Abbott and Costello comedy The Noose Hangs High (which wasn’t released until the spring of 1948, incidentally) and people on the streets rush to get home. But home offers no solace, as the convicts break into house after house looking for shelter, food, and weapons.

The cinematographer of Canon City was John Alton, who was responsible for brilliant work on many film noirs (most notably his collaborations with Anthony Mann). There aren’t a lot of memorable “noir” setups in Canon City, but overly stylized lighting wouldn’t have fit with the docudrama approach to the material. The darkness and the driving blizzard are terrifying enough filmed in a straightforward fashion. Canon City is the kind of movie where the cold gets into your bones just watching it.

Canon City is a film that is dated in many ways, but it still packs a punch if you can go along with the semi-documentary style. Writer-director Crane Wilbur gets the most out of his limited budget by filming inside the prison and in the rugged beauty of the southern Colorado landscape around Cañon City, and the pacing is swift and brutal once the breakout occurs.

Oh, and if you’re a Star Trek fan, keep your eyes peeled for a young DeForest Kelley as one of the dozen escapees.

You know what would be a great drinking game for a designated driver to play? Watching Race Street and taking a shot every time George Raft changes his expression.

You know what would be a great drinking game for a designated driver to play? Watching Race Street and taking a shot every time George Raft changes his expression.