Battleground (1949)

Directed by William A. Wellman

Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer

A lot of reviews of Battleground claim it was the first World War II movie to portray servicemen as fully human characters who experience fear and doubt, and not just as inspirational patriotic figures.

Whoever thinks this has probably not seen very many World War II movies made between 1941 and 1945. While Americans have never been great at understanding our enemies, we have always been good at exploring the vulnerability, fears, and doubts that our own soldiers experience in combat. Everything from Stephen Crane’s novel The Red Badge of Courage (1895) to Lewis Milestone’s film version of All Quiet on the Western Front (1930) presented nuanced views of men under fire.

During World War II, Hollywood films about the war tended to lionize servicemen and depict America’s involvement as vitally necessary, but the better ones, like Mervyn LeRoy’s Thirty Seconds Over Tokyo (1944) (with script by Dalton Trumbo), were also great human dramas.

I think the most significant antecedents to Battleground were two other films about men in the infantry: The Story of G.I. Joe (1945) and A Walk in the Sun (1945).

A Walk in the Sun was directed by Lewis Milestone, the man who directed All Quiet on the Western Front. It attempts to depict the mind of the American infantryman, through both dialogue and rambling internal monologues (a technique Terrence Malick would later use in The Thin Red Line). In keeping with the POV of the soldiers, the viewer is kept mostly in the dark about the larger significance of the violence, which punctuates the film in terrifying and confusing bursts.

The Story of G.I. Joe starred Burgess Meredith as embedded combat reporter Ernie Pyle and co-starred Robert Mitchum as the commanding officer of Company C, 18th Infantry. It was directed by William A. Wellman, the man who directed Battleground. Just like Battleground, the scenes of violence were swift and brutal, but the focus for most of the film was on the infantrymen themselves, and the boredom, extreme physical discomfort, and drudgery punctuated by fear that everyone who serves in combat experiences. Also like Battleground, most of the extras in The Story of G.I. Joe were actual soldiers who had served in combat.

The big studios dumped most of their existing war movies in theaters not long after V-E Day and V-J Day in 1945, rightly assuming that the public had little interest in war movies once the war was over. In the few years that followed, plenty of movies dealt with veterans’ homecomings (The Best Years of Our Lives, released in 1946, was the finest of these films), but I’m hard pressed to think of any American films from this period that directly dealt with the experience of combat. The only one I can think of is Mervyn LeRoy’s Homecoming (1948), but all of the fighting in that film was just the backdrop for a passionate and illicit romance between Clark Gable and Lana Turner.

So Battleground was unique in that it was a return to films about World War II that focused on the combat experience. Producer Dore Schary brought the project with him to Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer when he left RKO Radio Pictures. It was a passion project for him, and he really had to fight to get it to the screen, since MGM head Louis B. Mayer believed that the public was still tired of war films.

Schary’s persistence paid off. His tribute to the “battered bastards of Bastogne” was a huge hit with audiences, and was nominated for six Academy Awards, including Best Picture and Best Director. (It took home two Oscars, one for Best Story and Screenplay, and one for Best Cinematography, Black & White.)

As I said earlier, Battleground is firmly in the tradition of humanistic portraits of ordinary soldiers like The Story of G.I. Joe and A Walk in the Sun, but it does go further than any films made during World War II depicting how scared many ordinary infantrymen really were, and how strongly they could desire to be far, far away from the fighting.

One character in Battleground is counting the days until he rotates out of the Army, and is furious when he’s told that they’re surrounded by the Germans, and he’s not going anywhere. But typically of the film, he steels his courage and eventually manages to make jokes about how the Germans are committing war crimes by shooting at him, a civilian. Another character has a full set of false teeth, which he loses and then tries to be given medical leave for a few days. (That character is played by Douglas Fowley, who really did lose his teeth in an explosion while serving on an aircraft carrier in the Pacific.)

At one point in the film, two soldiers retreat and have to leave behind a wounded man, who hides himself from the Germans by crawling under the wreck of a jeep and covering himself with snow. The film never depicts any of the men’s acts as cowardly; they are badly outnumbered, and doing anything else would have been suicide for all of them.

The Oscar-winning screenplay of Battleground was written by Robert Pirosh, who served as a master sergeant with the 35th Infantry Division during the Battle of the Bulge. Pirosh based his script partly on his own experiences, but the film details the exploits of the 327th Glider Infantry Regiment of the 101st Airborne Division, so Lt. Col. Harry Kinnard, who had been the deputy divisional commander of the 101st at Bastogne, served as technical advisor. More than a dozen veterans of the 101st appeared as extras in the film and worked with the actors to ensure accuracy. (The film is relatively accurate except for a plot about German soldiers moving through the lines who are disguised as Allied soldiers, but this can be forgiven in the interest of creating suspense and tension. It is, after all, “only a movie.”)

The actors are all great, and many of them had actually served in combat. James Whitmore, who plays Sgt. Kinnie and was nominated for a Best Supporting Actor Oscar for the role, served in the Marine Corps in World War II. James Arness, who would go on to star in the 20-year run of Gunsmoke on TV, has a small role in the film, and was the most decorated soldier among the cast. (Arness was severely wounded at Anzio, and received the Bronze Star, the Purple Heart, the World War II Victory Medal, the Combat Infantryman Badge, and the European-African-Middle Eastern Campaign Medal with three bronze battle stars.)

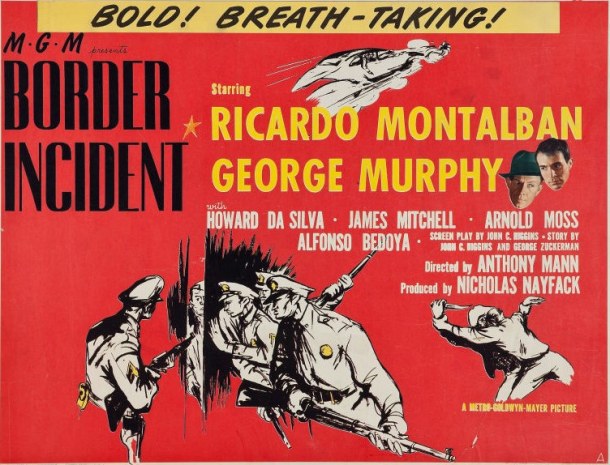

Consequently, Battleground is one of the most authentic World War II movies you will ever see, even though it might not seem that way to a viewer who has been weaned on the bloody CGI horrors of 21st-century war movies. However, if you’re conversant in the language of film, and can read what is being written on and off the screen, there’s one sequence that’s as brutal as anything you’ll ever see in a war film. Our heroes are surprised by German troops and in a fast-moving sequence, Ricardo Montalban rips a German soldier’s throat out with his teeth, Van Johnson stabs a German soldier to death with his bayonet, and John Hodiak bashes in the skull of a German soldier with the stock of his rifle.

I’ve read reviews of Battleground that refer to it as an “anti-war film.” I don’t know if this point of view springs from Steven Spielberg’s ridiculous assertion, made around the time that the philosophically incoherent Saving Private Ryan (1998) was released, that “every war movie, good or bad, is an anti-war movie,” but it couldn’t be further from the truth.

Although very few Hollywood films can simply be called “pro-war” films, a truly “anti-war” film would have to condemn any kind of armed conflict and celebrate pacifism as a viable and noble alternative. A truly “anti-war” film could not depict death and destruction in a highly aestheticized way, like Apocalypse Now (1979). And it could not celebrate the value of brotherhood under fire, as do Saving Private Ryan and Black Hawk Down (2001). No film that celebrates soldiers nobly putting their lives on the line for the greater good can ever be called an “anti-war movie,” any more than The Passion of the Christ (2004) can by called an “anti-crucifixion movie.”

I’m not condemning Battleground because it’s not an anti-war movie. I even thought the short, moving scene in which an Army chaplain explains why he thinks America’s involvement in the war is vitally necessary was one of the best bits of the movie.

But today is Memorial Day, and I think it’s worth considering, as we honor the sacrifice of people who laid down their lives overseas, that no war movie can ever replicate the experience of combat. No matter how realistic, the viewer is watching from a position of safety. And every war film is a tale told by survivors. The dead no longer have a voice.