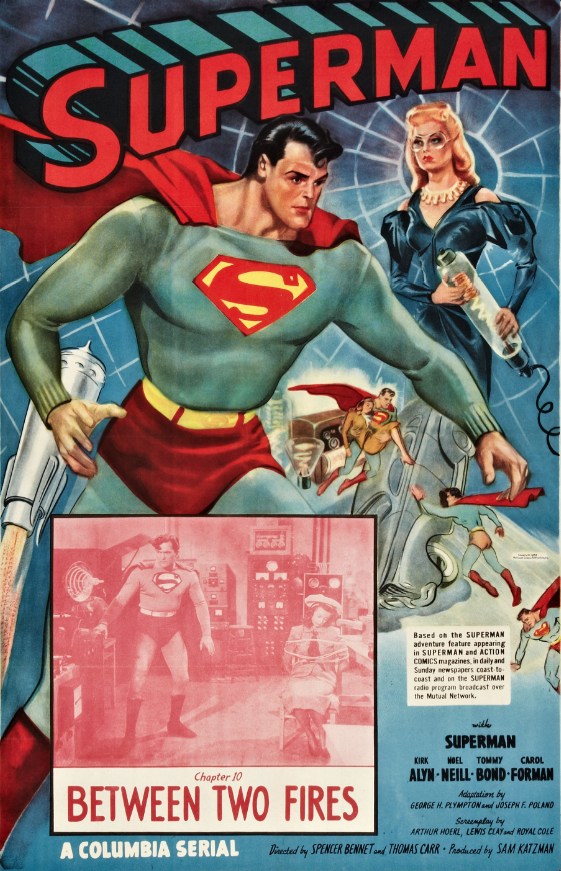

Superman (15 chapters) (1948)

Directed by Spencer Gordon Bennet and Thomas Carr

Columbia Pictures

Here it is, folks — the very first live-action Superman film.

Superman, in case you’ve been living under a rock, is one of the most popular and recognizable superheroes of the 20th century. Created by Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster, Superman made his first appearance in Action Comics #1 in June 1938. His popularity grew quickly, leading to a second comic series, simply titled Superman, in 1939, a radio serial — The Adventures of Superman — in 1940, a series of Max Fleischer cartoons (1941-1943), and a third comic series, which debuted in 1941 as “World’s Best Comics,” but was changed after the first issue to World’s Finest, and featured stories about Superman and Batman & Robin, as well as other DC Comics superheroes.

Aspects of all of those source materials can be seen in the 15-chapter serial Superman, which was produced by Sam Katzman for Columbia Pictures and directed by Spencer Gordon Bennet and Thomas Carr. Katzman produced a ton of cheapjack serials for Columbia, and he was sometimes known as “Jungle Sam” on account of all the action-adventure pictures he made that were set in tropical locations.

I’ve reviewed a few of Katzman’s serials on this blog already — Jack Armstrong (1947), The Sea Hound (1947), and Brick Bradford (1948) — but I’ve barely scratched the surface of his voluminous output. To be honest, I really don’t want to dig any deeper. Katzman produced some fun low-budget sci-fi pictures in the 1950s, but all of his serials that I’ve seen so far have been tedious, cheaply made, and poorly acted, and Superman is no exception.

In 1948, the Max Fleischer animated shorts about Superman were still the most impressive cinematic versions of the character. They were gorgeously animated, full of vibrant color, packed with action, and even featured the talents of Bud Collyer, the voice of Superman on the radio. In short, they were comic books come to life.

In fact, they were so impressive that Katzman’s black and white serial Superman features an animated Superman in all of the flying sequences. It’s a very different approach to a flying superhero than the practical effects featured in Adventures of Captain Marvel (1941), which for my money is the greatest serial ever made.

Adventures of Captain Marvel featured a dummy that zipped along a wire, which sounds cheesier than it is. The effect actually works quite well, thanks to simple techniques like reversing the film so the dummy can fly upward, shooting in silhouette, and creative editing. The animated flying sequences in Superman, on the other hand, are well-done for what they are, but the technique of turning live action into animation and back again was always jarring for me.

If you’re a Superman fan, this serial is a must-see for its historical value, but it’s just not that great. The low-budget black and white filmmaking is less vibrant than the Max Fleischer cartoons, the storytelling is less inventive and involving than the radio show, and the physical appearance of Superman just isn’t as impressive as it was in the comic books.

At the beginning of every chapter, the Superman comic magazine flashes on screen, then Kirk Alyn bursts from its pages and stands there for awhile looking as if he’s not sure what he should do next.

Alyn was a 37-year-old actor who’d had bit parts in a bunch of B movies, but this was his first leading role. Alyn has the right face and the right hair to play Superman, but his body, mannerisms, and physical presence all feel wrong. (This is another area where Adventures of Captain Marvel excelled. Tom Tyler looked very much like the Captain Marvel of the comic books, and his physicality was impressive.)

Alyn fares a little better as Superman’s alter ego, mild-mannered reporter Clark Kent. I like the slightly alien edge he gives the character, but in some scenes his alien peculiarity just seems like bad acting.

My favorite actor in Superman is Noel Neill, who was so good as Lois Lane that she went on to play Lois in the Adventures of Superman TV series with George Reeves that premiered in 1951. The same honor was not accorded to either Tommy Bond (who plays cub reporter Jimmy Olsen) or Pierre Watkin (who plays Daily Planet editor-in-chief Perry White). I actually really liked Watkin as Perry White, but I thought Bond was obnoxious and irritating as Olsen, and not just because he’s the guy who played Butch in the Our Gang comedies.

Also, Los Angeles and the surrounding countryside don’t make for a very convincing Metropolis, but California locations are to be expected in any serial.

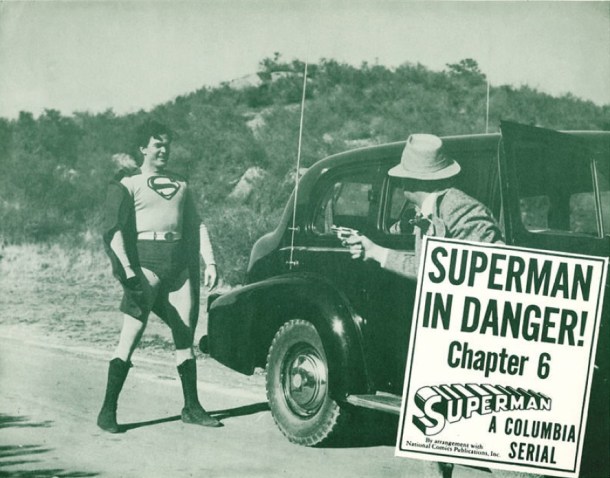

The antagonist of the serial is called The Spider Lady (Carol Forman), a master criminal who wears a slinky black cocktail dress and a black domino mask. The Spider Lady is after a MacGuffin called a “reducer ray,” and like every good serial villain, she has an army of disposable goons who carry out her cockamamie plans in chapter after chapter. She also has a henchman named Hackett who is introduced in Chapter 6, “Superman in Danger.” Hackett is a brilliant but deranged scientist who has broken out of prison. He’s played by Charles Quigley, who starred in The Crimson Ghost (1946), and other serials.

I love serials — even the bad ones — and I certainly enjoyed aspects of Superman. But every superhero movie is only as convincing as its lead actor, and Kirk Alyn just isn’t up to the task. I’m sure in 1948 it was thrilling for plenty of kids to see their hero come to life on the big screen. It was a time when Superman was such a mythic, larger-than-life figure that the actors who played him were never credited. When Bud Collyer made an announcement about something that wasn’t a part of the radio show’s serialized story, he was still introduced as “Superman.” Similarly, in the cast of characters list that flashes on the screen at the beginning of every chapter of Superman, Kirk Alyn is the only actor whose name isn’t listed. The first name in the credits is simply SUPERMAN.

Still, I wonder how many children in 1948 were somewhat disappointed by Kirk Alyn (perhaps in ways they couldn’t verbalize). After all, he doesn’t have the impressive voice of Bud Collyer, and he’s so much scrawnier than the strapping hero of the comics. Worst of all, he flits around like Peter Pan, and his cape frequently gets in the way during the action.