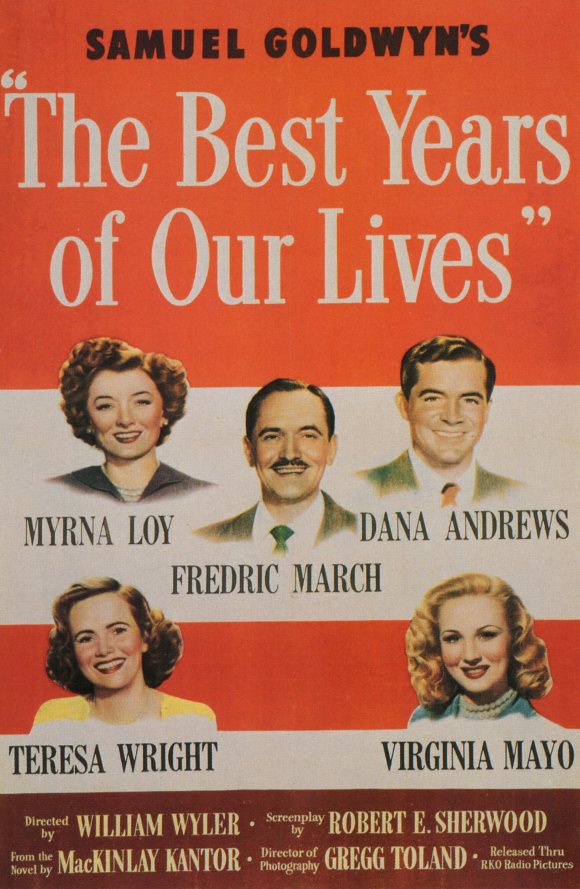

The Best Years of Our Lives (1946)

Directed by William Wyler

RKO Radio Pictures

William Wyler’s The Best Years of Our Lives premiered in New York City on November 21, 1946, and in Los Angeles a month later, on Christmas day. It was a hit with both audiences and critics, and was the biggest financial success since Gone With the Wind in 1939.

The film swept the 19th Academy Awards, winning in all but one category in which it was nominated. The film won best picture, Wyler won best director, Fredric March won best actor, Harold Russell won best supporting actor, Robert E. Sherwood won for best screenplay, Daniel Mandell won for best editing, and Hugo Friedhofer won for best score. (The only category in which it was nominated and did not win was best sound recording. The Jolson Story took home that award.)

There are several reasons for the film’s financial and critical success. It perfectly captured the mood of the times. In 1946, returning servicemen faced an enormous housing shortage, an uncertain job market, food shortages, and a turbulent economy (price controls were finally lifted by the O.P.A. around the time the film premiered). Combat veterans also faced their own personal demons in an atmosphere in which discussing feelings was seen as a sign of weakness. By telling the stories of three World War II veterans returning to life in their hometown, The Best Years of Our Lives held a mirror up to American society.

The biggest reason for the film’s success, however, is that it’s a great movie. Plenty of films made in 1945 and 1946 featured characters who were returning veterans, but none before had shown them in such a realistic, unvarnished way. The Best Years of Our Lives doesn’t try to wring tragedy out of its characters’ personal situations. It’s an overwhelming emotional experience precisely because it doesn’t strain for high emotions. The film earns every one of its quietly powerful moments. Hugo Friedhofer’s score is occasionally overbearing, and a little high in the mix, but at its best it’s moving, and a fair approximation of Aaron Copland’s fanfares for common men. Gregg Toland’s deep focus cinematography is phenomenal. Every image in the film — the hustle and bustle of life in a small American city, the quietly expressive faces of its characters, and the interiors of homes, drugstores, bars, banks, and nightclubs — is fascinating to look at. (Toland was Orson Welles’s cinematographer on Citizen Kane, and he was an absolute wizard.)

The actors in this film are, without exception, outstanding. Fredric March plays Al Stephenson, an infantry platoon sergeant who fought in the Pacific, and who returns to his job as a bank manager. Myrna Loy plays his wife, Milly, Teresa Wright plays their daughter, Peggy, and Michael Hall plays their son, Rob. Dana Andrews plays the shell-shocked Fred Derry, a decorated bombardier and captain in the Army Air Forces in Europe, who returns home to his beautiful wife Marie (Virginia Mayo), whom he married immediately before leaving to serve. Now that the war is over and they are living together, they realize they have very little in common. Harold Russell plays Homer Parrish, a sailor who lost both his hands when his aircraft carrier was sunk.

Russell was a non-professional actor who lost his hands in 1944 while serving with the U.S. 13th Airborne Division. He was an Army instructor, and a defective fuse detonated an explosive he was handling while making a training film. Russell’s performance is key to the success of the film. An actor who didn’t actually use two hook prostheses in his everyday life wouldn’t have been able to realistically mimic all the little things that Russell does; lighting cigarettes, handling a rifle, playing a tune on the piano. More importantly, Russell’s performance is amazing. From the very first scene that the camera lingers on his face as he shares a plane ride home with March and Andrews, I felt as if I knew the man.

Russell is so convincing as a man who has quickly adapted to his handicap that it’s gut-wrenching to watch as his exterior slowly breaks down, and we’re drawn deeper into his world. Homer Parrish has a darkness inside him, and he carries with him the constant threat of violence; bayonets adorn the walls of his childhood bedroom and he spends his time alone in the garage, firing his rifle at the woodpile. His next-door neighbor and childhood sweetheart Wilma (Cathy O’Donnell) keeps trying to get close to him, but he pushes her away. In a lesser film, this all might have led to a violent and melodramatic finale, but it merely simmers below the surface, informing his character. Instead, the most emotional scenes with Homer take place in smaller ways, such as when we see that he is not as self-sufficient as he seems, and needs his father’s help every night to remove his prostheses before he goes to sleep.

The Best Years of Our Lives is a great film, and should be seen by everyone who loves movies and is interested in the post-war era. It’s long — just short of three hours — but it didn’t feel long to me. The running time allows its story to develop naturally as the characters enter and re-enter one another’s lives. It also felt more real than any other movie I’ve seen this year. (I can’t think of another movie that wasn’t about alcoholism that featured so many scenes of its characters getting realistically drunk.) And despite all the personal difficulties its characters face, it’s ultimately an uplifting film, full of quiet hope for the future.