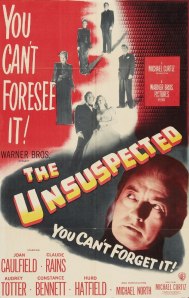

Orson Welles’s The Lady From Shanghai premiered in France on Christmas Eve, 1947, and in the United States nearly half a year later, on June 9, 1948.

Orson Welles’s The Lady From Shanghai premiered in France on Christmas Eve, 1947, and in the United States nearly half a year later, on June 9, 1948.

The film is something of a minor classic now, but at the time of its release it was generally a disappointment; a disappointment to critics, to the studio, to audiences, and to Welles himself, who had little control over the final product released into theaters.

The Lady From Shanghai was filmed in 1946, and the original cut ran more than two and a half hours. Executives at Columbia Pictures made numerous cuts, and the final musical score was not to Welles’s liking. The litany of complaints from all sides were legion, and are outside the scope of this review.

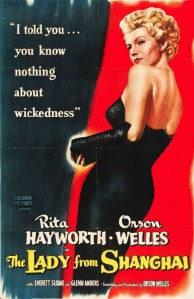

But before I get into a discussion of the film itself, I need to mention the complaint that I find most mystifying. Welles chose to radically alter the looks of his leading lady, Rita Hayworth (to whom he was married from 1943 to 1948), by chopping her long tresses and dying her hair platinum blond. This decision caused a whirlwind of controversy, and was blamed by some in Hollywood for the dismal box office performance of The Lady From Shanghai.

Was the movie-going public in 1948 composed entirely of people whose tonsorial proclivities were identical to the Son of Sam’s? I think that Rita Hayworth is stunningly beautiful and alluring no matter what her hairstyle, and The Lady From Shanghai is all the proof I need.

Was the movie-going public in 1948 composed entirely of people whose tonsorial proclivities were identical to the Son of Sam’s? I think that Rita Hayworth is stunningly beautiful and alluring no matter what her hairstyle, and The Lady From Shanghai is all the proof I need.

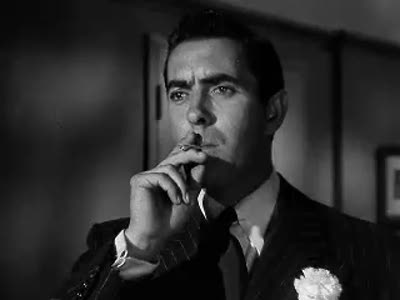

The Lady From Shanghai stars Welles as a “black Irish” rascal and drifter named Michael O’Hara who saves a beautiful young woman named Elsa Bannister (Hayworth) from a group of muggers in Central Park, and then becomes embroiled in a byzantine scheme that involves a faked death.

The plan is hatched by her husband’s law partner, George Grisby (Glenn Anders), who wants O’Hara to confess to murdering him after Grisby leaves the country, never to return. The rub is that without a body, the authorities won’t be able to convict O’Hara, and he’ll pocket a lump sum of cash for his trouble while Grisby pockets the insurance money. But Elsa’s husband, Arthur Bannister (Everett Sloane), has noticed the way Elsa and O’Hara make eyes at each other, and he’s got his own wild scheme.

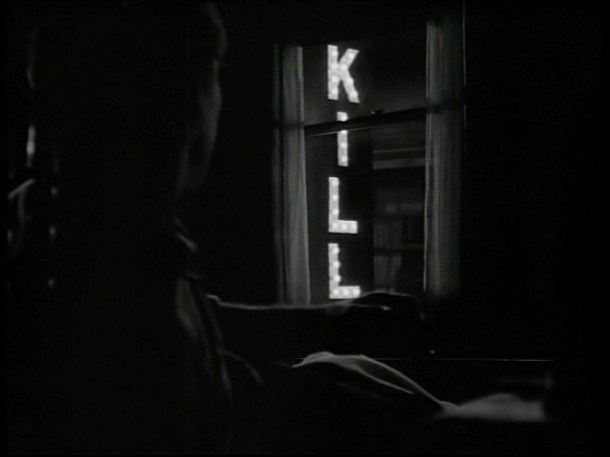

Even for a movie that was hacked down from 155 minutes to just 87, The Lady From Shanghai covers a lot of ground, and much of it is crazy. O’Hara accompanies the Bannisters and their entourage on a yacht tour of Mexico on their way from New York to San Francisco before the plot really gets rolling. Then, after the triple-cross scheme plays out, there’s a farcical courtroom scene that is genuinely funny and truly bizarre. Finally, there is a wild and phantasmagoric journey through San Francisco’s Chinatown that culminates in a chase through an abandoned fairground, and the film’s famous climax in the hall of mirrors of The Crazy House.

Given the studio-imposed cuts in the film’s running time, it’s probably not Welles’s fault that the plot is full of holes. But it’s hard to imagine any additional footage or story elements that would make the wild shifts in tone and byzantine plot any more digestible.

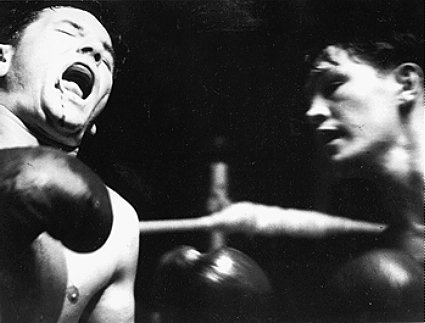

Ultimately, though, it really doesn’t matter. If you can get over Welles’s bad Irish accent and the general confusion of ideas in The Lady From Shanghai, it’s a brilliant, engrossing film that’s a joy to watch. Besides the gorgeous black and white cinematography and wonderful performances from Sloane, Hayworth, and Anders (and Welles, more or less), Welles is a director who was decades ahead of his time in terms of action and pacing. The slightly sped-up camerawork during fight scenes and the rapid editing isn’t like anything else you’ll see from the mid- to late-’40s.

There are a lot of things about The Lady From Shanghai that are totally unlike anything else in cinema at the time of its release. Welles’s reach usually exceeded his grasp, but as a director I think he was without parallel. The Lady From Shanghai may not be a perfectly formed work of art like Citizen Kane (1941), but it’s a fascinating and incredibly entertaining film.